Microsoft Office migration from Source Depot to Git

Part 7: Office Migration from Source Depot to Git, or how I learned to love DevEx.

After going in deep in product, I found myself drawn to a different challenge: making other developers more productive. As one of my biggest mentors would always say: “Developer productivity is always ‘Multiplier work’, especially in places where you have a lot of developers. By saving a couple minutes from every developer, every day, you’ve saved years of human life waiting for stuff.”

The project that really forged me was the Office migration from Source Depot to Git.

Source Depot: A Journey to the Past

Come kids, gather around. Let me tell you youngsters about the ancient times of source control, back when dinosaurs roamed the Earth and before Git and GitHub were even a twinkle in Linus Torvalds’ eye.

In the early 2000s, Microsoft faced a dilemma. Windows was growing enormously complex, with millions of lines of code that needed versioning. Git? Didn’t exist. SVN? Barely crawling out of CVS’s shadow. No, children, these were the dark ages of version control.

Perforce was one of the few commercial options available—expensive but powerful for its time. Microsoft, being Microsoft, decided to build their own system based on Perforce technology. And thus, Source Depot was born.

Using Source Depot was weird, it felt a little bit like programming with oven mitts on: iterations were faster, but branching and switching state were painful. Also, it didn’t help that a single get of the office repo took some hours. Want to check out code? Type sd get (a.k.a osync) and wait. And wait. And perhaps make yourself a sandwich while waiting.

Branching? Oh, my sweet summer children. Creating a branch wasn’t the casual git checkout -b you casually toss around today. It was an event. Something you planned for, scheduled, and possibly created a small ritual around. (And pray you don’t have a name conflict.)

Everything was centralized—if the network went down, productivity ceased. If you were working remotely? Well, VPN and prayer were your only options. (And VPN was only to get into the AAD network and join the REDMOND domain.)

The worst part? Merging changes (or how we, the ancients, call them Reverse Integrate and Forward Integrate). Branch admins would constantly work on doing this process. You’d be respected by being the RI and FI admin for your part of your world.

Despite all this, Source Depot served Microsoft for many years. It was reliable, if nothing else, a sturdy workhorse. But by the time I encountered it, this workhorse was clearly showing its age.

This, my children, is why when we finally moved to Git, it took me, plus some hundreds of engineers, years to finalize.

Most challenging of all, Source Depot was deeply integrated into Microsoft’s build systems, release pipelines, and developer workflows. It wasn’t just source control, it was the foundation for how software was built at Microsoft.

Migrating OneNote to Git

At some point, the central developer experience organization (Office Engineering) decided that a migration to Git was needed. Not only was Source Depot a huge money sink, but patching it and maintaining it was a marathon job. They also had the grumbling of existing employees and new hires about not getting “transferable job skills”. This is how Office started their multi-year journey to migrate to Git.

This required years of planning. One day, I’ll gather the warriors who led this odyssey and ask them in detail their war stories over coffee. But from my tiny perspective, the challenges were the following:

Office has different schedules for different customers

- LTSC (which ships in a > 6 months schedule, it’s very stable)

- Semi-annual updates

- Monthly updates

- Insiders

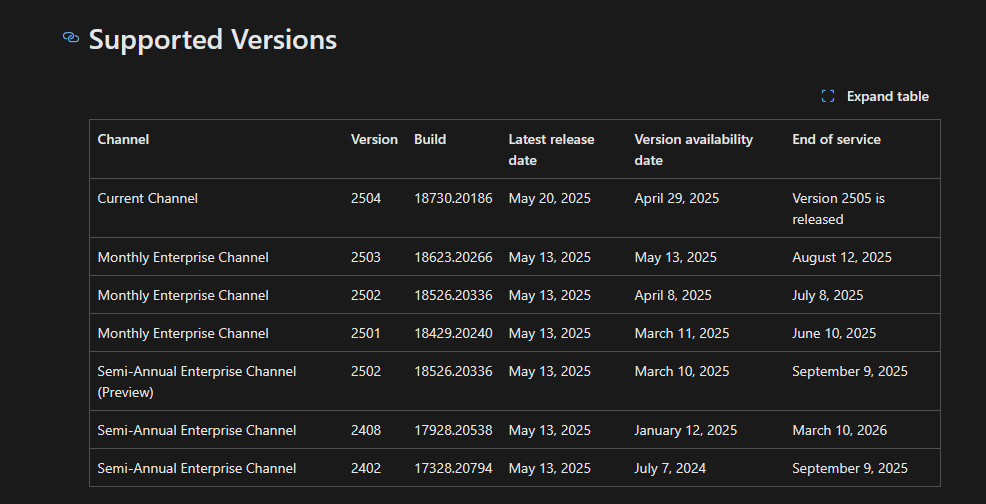

Example of Office versions and naming schemes today

Example of Office versions and naming schemes today

Which meant that any migration had to support the old and new system for months. Not only that, but Office versioning had to stay consistent between builds (which looked something like this 16.0.18730.20186, the latter part being the build number). This included triggering all the correct validation that happened in the previous system, keeping tests working (migrating the legacy test infra that only works on IE) and more.

The scale of Office

Today, as I type these words, I work at Snowflake. Snowflake has around ~2,000 engineers. When I was in Office, Office alone was around ~4,000 engineers. This required enormous coordination of the Office Engineering system with teams all around Office (Word, Excel, Powerpoint, Sway, Publisher, Access, Project, OneNote, Shared Services (OSI), Shared UX, + everything in the web). Given these constraints, Office Engineering (OENG) created a “champion”/hub-spoke model. By designating one “Developer Satisfaction” champion per team, they would have an effective liaison per-team to not only migrate to Git, but to be able to have feedback channels for their entire org.

As the OneNote Developer Experience champion, I had front-row seats to one of the largest version control migrations in software history. Here’s how we pulled it off, though we made plenty of mistakes along the way.

Microsoft had to collaborate with GitHub to invent the Virtual File System for Git (VFS for Git) just to make this migration possible. Without VFS, a fresh clone of the Office repository (a shallow git clone would take 200 GB of disk space) would take days and consume hundreds of gigabytes. Even basic Git operations like status checks would timeout (hilarious to see a git status churning along for a minute). VFS creates a virtual view of the repository, downloading files only when you actually need them.

The Windows team faced similar challenges and had already started down this path, but Office pushed the boundaries even further. When your codebase is so large that you have to reinvent version control to migrate it, you know you’re operating at a different scale than most software projects.

Phase 1: The Parallel Universe

The challenge: how do you migrate a live codebase used by thousands of developers without breaking anything?

Our solution was “the parallel universe.” There was a Git-native codebase that continuously synced with Source Depot. Think massive, automated git-svn bridge, but for Source Depot.

This was immense and took way longer than estimated. Source Depot’s branching model was fundamentally different from Git’s. It actually took three tries in different years to get to a working bridge. Where Git thinks commits and merges, Source Depot worked with “changelists” and “integrations.” We had to map Source Depot’s branch hierarchies to Git’s DAG structure while preserving commit authorship and timestamps. The hardest part to keep consistent was the Reverse Integration/Forward Integration and make sure they were consistent with the Git version.

The sync service was a long process, AFAIR:

onenote's private branch (sd)

-> officemain

-> main sd repository

-> git bridge

-> officemain git

-> onenote's private branch (git)

The machine churned developer’s hopes and dreams, but ran effectively 24/7, ingesting every changelist and making its way through Git. When we had early testers, we asked them to make changes to parts of code that are not “high traffic.”

Phase 2: Proving Equivalence

Having a Git mirror was only half the battle. We needed to prove everything still worked exactly the same.

This meant running our entire test suite against both codebases. Every day. A lot of semantics have been built over the years to respect the way everything worked before. Office’s build system was so complex that tiny differences in how to run a test could cascade into different binary outputs. We spent months debugging line ending handling, case sensitivity issues, and test output mismatch. All this in a system called “bb” (I think it stands for big button? as you used to push the big button and have it test the world).

To paint a picture, oasysnet/bb could only be loaded on IE 11. You submitted a source depot patch (or a branch in git) went out, ran a bunch of tests, and returned with results. The results and logs would be in awful undecipherable formats, and you had to do an offering to the gods (your closest senior engineer) and hoped that they’d help you understand it.

My wife for a while told me “That bb guy in your company seems pretty bad, they should fire him, you are all always complaining about him.”

The breakthrough came when we achieved our first “green across the board” day where every test passed identically on both systems. That’s when we knew the parallel universe was ready.

The Human Side: Overcommunication

Technical migrations fail because of people, not technology.

With 4,000+ engineers across time zones, teams, and product schedules, communication was the difference between success and chaos. We used a hub-and-spoke model where each team designated a “Champion.” Champions met weekly and became the translation layer between central engineering and their teams. This created around 80 direct communication channels instead of broadcasting to 4,000 people. I was a champion for the ~120 peeps from OneNote.

We communicated the same information through multiple channels: weekly emails, Teams, wiki docs, team presentations, and office hours. The rule: if something was important, people heard it at least 3 times through different mediums.

When things went wrong (frequently), we were brutally honest. “The sync failed overnight, builds are delayed 4 hours, here’s exactly what happened and our timeline.” This transparency built trust, even when we screwed up.

Training: Making Git Feel Native

You can’t throw Git documentation at Windows developers who’ve used Source Depot for a decade and expect magic. A lot of people complained about how obtuse Git was. And they were right! There are many conventions that are not easy to grasp in Git.

We built training environments that showed people the commands from Source Depot to Git. People could clone the actual repository in a sandbox and practice common workflows: feature branches, code reviews, merges, disaster recovery, and Visual Studio integration.

The key insight: people needed to feel competent before going live. Fear of breaking things was the biggest barrier to adoption.

We created a video library covering common scenarios. Not polished marketing videos but screen recordings of real developers working through real problems. Authenticity mattered more than production value.

Rollback Strategy: Planning for Failure

The scariest question: “What if this goes wrong and we need to go back?”

Once we started to go live, we gave our Director/GEM a “red button.” You can ask to stop the migration at any time if it’s hurting productivity excessively. No questions asked. This happened one time because of a performance regression, but leadership appreciated having this button to press and make sure we could roll and rollback safely.

I’m not sure if Source Depot is still running, but I wouldn’t be surprised if it has to be kept for years for the archives of old builds. So that every commit, branch, and piece of history can remain accessible, providing psychological safety even if rarely used.

Long-term Results

Six months later, we surveyed all OneNote developers. Results were better than expected, though not perfect.

A lot of people felt refreshed by having better transferable skills to the industry. Our onboarding times were slashed by half. AFAIK, 89% preferred Git to Source Depot. Build times improved with VFS. Developer productivity scores increased significantly. Code reviews became faster and more collaborative.

On a personal side, I do think people worked faster in Git and were more productive, and new hires were productive immediately.

Lessons for Large-Scale Migrations

Invest way more in communication than you think you need. Technical challenges are solvable with time and smart people, but people challenges kill projects faster than any bug.

Build the parallel universe first. Prove equivalence before switching. “It should work” isn’t good enough at this scale.

Find champions early and invest heavily in their success. They become force multipliers in ways hard to quantify but absolutely essential.

Plan for rollback from day one. Confidence to fail fast prevents catastrophic failures.

Measure satisfaction alongside technical metrics. Productivity is as much about perception as performance. Read my blog about how developer productivty is 99% perception.

The real migration were the friends we made along the way.

The Office migration took years of planning. The OneNote migration took around 6 months of execution. The real lesson wasn’t about version control but about orchestrating change across thousands of people without breaking what they depended on.

When I think about today’s big migrations—cloud, monolith decomposition, framework upgrades—the playbook is surprisingly similar. Build parallel systems, prove equivalence, communicate relentlessly, and always have a way back.

I wish I could go deeper into some of the topics (build infra, test infra, office versioning, on-prem, contractual obligations, semi-annual channels, certification of builds, BOMs, caches, etc.) that had to happen here, but I think they are a lot of people that can explain this part a lot better than I can. Maybe one day?

What’s the largest technical migration you’ve been part of? What worked, what didn’t, and what would you do differently?

Other blog posts to read!

Get my posts on your mail

When I write something new, sign up to hear more.

Thank you!

You have successfully joined my subscriber list.

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0