Hell Is Us Hands-On Impressions – Show, Don't Tell

“Often people ask me, ‘How would you describe the game? What kind of game is it?’”, muses Rogue Factor creative and art director Jonathan Jacques Belletête. “It's just a good old adventure game like back in the days, you know? It's like [when] you booted up Zelda: Link to the Past. You didn't question it.”

After playing a few hours of Hell is Us, in which I explored contemporary-looking European villages and countrysides laden with seemingly alien ancient temples and inhuman monstrosities, I think players will raise quite a few questions. And those mysteries are what make this upcoming action-adventure game so alluring.

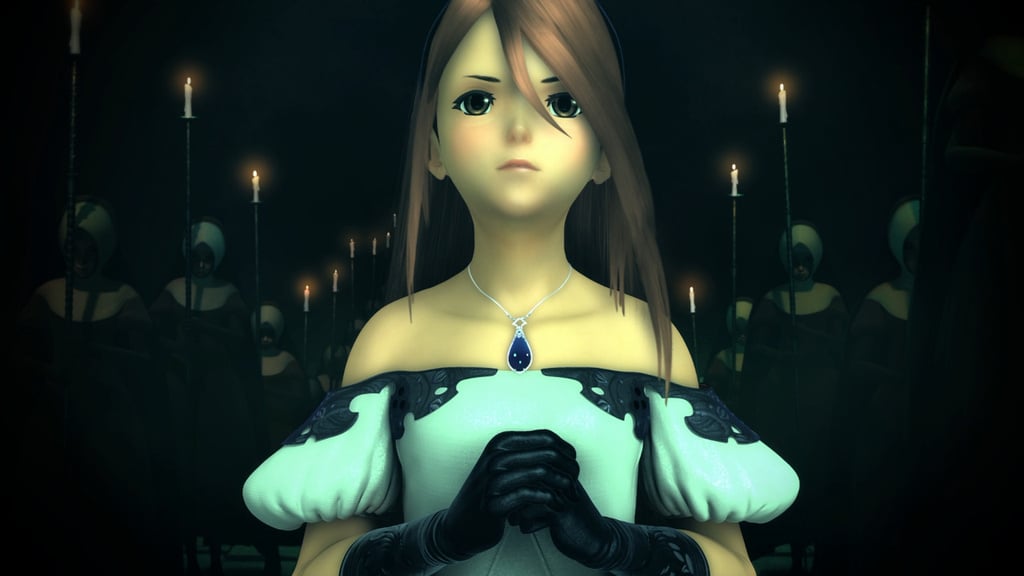

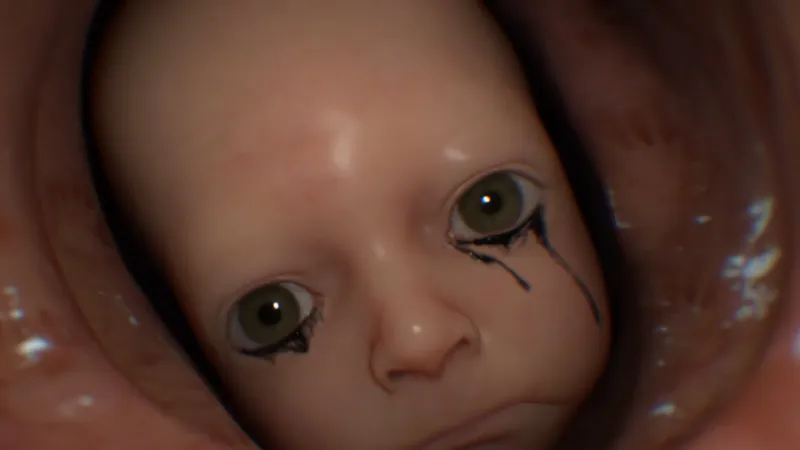

Hell is Us is the debut title from Rogue Factor, a small Montreal-based studio led by Jonathan Jacques Belletête, who previously spent years working at Ubisoft as the art director for the Deus Ex franchise. The game stars Rémi, a soldier born in Hadea, a fictional European nation torn apart by war. For years, the country has isolated itself from the world, meaning no one can enter, and its inhabitants can’t leave. However, Rémi’s parents managed to smuggle him out of the country as a baby, hoping he could live a better life abroad. Rémi is sent to Canada and grows up living in a variety of foster homes. While he’s had it objectively better than his people in Hadea, he’s grown up with a sense of abandonment without his family, which has plagued him with questions. Who were his parents? Where are they now? Are they even still alive?

Fast forward to 1993, and this yearning for answers burns a hole in the now-adult Rémi large enough to spur him to accept a peacekeeping mission in a country neighboring Hadea. He uses this opportunity to go AWOL and sneak into his homeland. While he manages to get in, he jumps from the frying pan into the fire. First off, he has next to no information on his parents to go on, so tracking them down will be extremely difficult. Moreover, Hadea is in the grip of a brutal civil war that has raged for two years at this point. But the most unexpected and terrifying development is the presence of a powerful, otherworldly threat that has seemingly swept the nation.

Rémi’s lack of information means he’ll need to glean details wherever he can find them. This search for answers represents the core of Hell is Us; handing players the reins to figure things out on their own. Belletête and his team grew up loving adventure games from the ‘90s, particularly in how they tended to trust players to solve problems without holding their hands too much. Belletête believes many modern triple-A games have become so obsessed with attracting a broad player base that they’ve become overly guided in their approach.

Belletête calls this approach “silver plattering”, describing how modern games hand-deliver the answers with minimal effort from the player. As a result, he believes truly great level design is less emphasized; why bother when an omnipresent arrow tells players exactly where to go? “If you think about visuals in most games, they're there to be pretty and to support the themes, right?” says Belletête. “But they're not really there to tell you what you're supposed to do or how to decipher certain things.”

With Hell is Us, Belletête wants to emphasize what he calls “player plattering”: trusting that players are smart and savvy enough to figure things out on their own. That means designing strong levels and puzzles that encourage careful observation, creating a greater sense of immersion in the space. Pushing players to rely more on their wits highlights Hell is Us’ primary mantra: Knowledge is power, but it has to be earned.

Searching For Answers

My demo begins in Senedra Forest, one of Hadea’s several large open hubs. Hell is Us is not a true open-world game, but you’d be fooled into thinking so, looking at the map, which features many locations. There are no map markers, no quest journals telling you exactly what you should be doing. Rémi’s only tip is a keepsake pointing to a village called Jova, but he has no clue where that is. After taking a short stroll on a forest road, I locate a small house owned by an elderly farmer. I don’t know his name; he hasn’t told me that yet. I have to ask him for such details, highlighting one of the game’s most prominent elements: investigations.

During conversations, you can ask characters questions about a specific investigation and more general inquiries, such as their insights on Hadea as a whole or the civil war. These answers may yield new information on these subjects, so it's worth getting their perspectives. Each investigation has a flow chart in the menu, which tracks various mysteries tied to it. Clues, whether a person, item, or event, have a section on the chart updated with new info as you learn more about them. A person, for example, has categories that gradually fill out, such as their location, a general description of them, a list of key facts, and the investigation they’re tied to.

The old timer introduces himself as Ernest Caddell. I ask Ernest if he knows how to reach Jova, and he replies by stating it’s in Acasca Marshes, “quite a ways” from where we are. Ernest also mentions that I’ll need a vehicle to reach it. He doesn't have one, but a group of soldiers who recently arrived in an APC vehicle might. When I ask where the APC is parked, Ernest says it’s “just beyond the woods to the North”; I just need to follow the wind chimes, which lead the way through.

In most games, this information would generate a map icon that I would simply follow. This would result in me staring at a waypoint on a minimap instead of observing my surroundings, which can detract from the immersion. The opposite is true in Hell is Us. Ernest’s directions are not flavor text trivialized by a magic arrow. You literally need to follow his instructions, meaning I have to determine which direction was north (Rémi thankfully has a compass) and head that way until I encounter the first wind chime, which I hear before I see. The subsequent chimes aren’t far apart, so it doesn’t take long to find my way to my destination. Even this simple exercise is far more engaging than watching my character icon inch closer to another dot on a minimap. It is a small example of how you can expect to explore Hadea.

Gleaning information like this makes Hell is Us feel reminiscent of a classic point-and-click adventure game. For example, you collect clues and key items that, in addition to adding new information to your investigation flowcharts, can also be equipped to your hotkey item wheel for easy reference in-game. Speaking to NPCs is as much interrogation as conversation and becomes a lengthy affair as you wring as many leads out of them as possible. Belletête tells me the design similarities are intentional, as one of the primary inspirations for the investigative element is the 1997 Blade Runner adventure game by Westwood Studios, a game he describes as a “masterpiece.” That game features a complex system of following clues and leads, so Rogue Factor distilled that approach into a comparatively simplified format for Hell is Us to avoid the pitfalls of the adventure genre. Belletête may want players to flex their brains more, but he and Rogue Factor are conscious about ensuring the experience doesn’t become too obtuse or frustrating.

While searching for leads, exploration can also uncover special items that trigger side quests called Good Deeds. One example is a gold watch I find that belongs to someone named Otis, whose name is engraved on the back. This adds a note to my log, though, like everything else, saying you’ll need to gather more intel to learn who and where Otis is, presenting another puzzle to chew on.

Puzzle-solving is a significant element of Hell is Us. You can find puzzles all over the map, whether as smaller trials or more elaborate exercises, the latter of which I often encounter in the game’s dungeons. One optional riddle involves using a child’s message to locate a hidden stash of goodies by finding a path of landmarks that match the writer’s descriptions. A more involved exercise involves opening a door by rotating circular rings of symbols that are lined up in a specific order. Solving this conundrum requires studying carvings around my environment, with subtle clues pointing toward the appropriate sequence in which the rings must be organized.

Belletête describes the puzzles on the main story path as manageable, except for two later game exercises he says “get pretty spicy.” Riddles off the beaten run the gamut of difficulty levels, which Belletête says are labeled internally as Very Easy, Normal, Very Hard, and “Reddit.” That last tier refers to puzzles so involved that they will likely require the player community to work out the solution together. Rogue Factor is still tuning and refining the difficulty of puzzles, but I’m curious to see just how demanding they can be.

Exploring dungeons involves the standard fare of battling enemies, finding keys to open locked passages, and discovering critical and optional quest items. The dungeons I explore have an ancient alien vibe to their design; old, and very much not designed by human hands. Dungeons can be found all over the map, both big and small, and some require solving a riddle just to discover them. The reveal of one particular dungeon in an open marshland was especially impressive due to its cinematic nature and how its emergence transformed the surrounding environment. I can’t wait to poke around and find more hidden structures like these, sometimes right under players’ noses.

Combat Isn’t What It Looks Like

Belletête describes Hell is Us as roughly an even split between exploration (which includes puzzle-solving) and combat. The third-person melee combat feels deliberate, with players using weapons such as a sword, polearm, or, my favorite, dual axes. Every swing forces you to commit to attack animations, meaning timing is key. Holding the attack button charges your weapon, unleashing a more powerful attack. The combat is solid but didn’t wow me initially, though unlocking skills allows you to perform fun special attacks, such as unleashing a whirlwind assault where Rémi spins frantically, mowing down everyone in his path. You can dodge or parry attacks, and actions are dictated by a stamina meter. Despite his average frame, Rémi feels like a tank; his weighty dodge rolls remind me of playing bulkier classes in a Souls game. Based on this description, you’d be forgiven for assuming Hell is Us is a Soulslike, especially when seeing it in action, but Belletête stresses this is not the case.

“Making a third-person melee combat system nowadays, it's difficult to ignore certain vibes that From Software have brought to the table in the past 15 years,” says Belletête. “So there's some similarities there. Are we edging the line sometimes in some places? Maybe. But no, the intention is to be a lot more mid-core.”

Combat can be tough, but a helpful assist can keep you in the fight. When attacking enemies, a glowing white ring will briefly appear around Rémi. Hitting a button when this happens allows you to regain a portion of lost health. Functionally, it works like an Active Reload in certain shooters (e.g., Gears of War), but instead of reloading ammo, you’re replenishing health, and the amount of which varies. Nioh 2 fans may recognize this as a take on the Ki Pulse stamina recovery system from that game, which Belletête confirms as a direct influence. It took a while to get accustomed to this system; in the heat of combat, I often forgot to use it and lost a lot of health I could have recovered. But it’s a helpful assist that adds another fun wrinkle to the often challenging melee duels.

The primary enemies are otherworldly humanoid beings sporting milky white skin and gaping holes where a face or abdomen would be. They look like living abstract art sculptures. They come in various types, including one with giant wavy flaps on its back like it's wearing a fleshy wingsuit. Some also have the nasty habit of expelling bizarre kaleidoscopic entities of energy that double as standalone threats. These take many abstract shapes and sizes, often resembling living blown glass sculptures that vibrate as they emit spine-tingling shrieks and howls. They’re a stark contrast to their comparatively mundane-looking hosts.

In my session, combat was generally more intimate, often pitting me against a single foe. Encounters become notably tougher when two or three threats enter the fray, so it helps that Rémi has a sidekick in the form of a drone. Although Hell is Us unfolds in the early ‘90s, drones exist in this alternate timeline, though this one does more than fly around. In combat, Rémi can command the drone to distract targeted foes, allowing players to flank them or to isolate them from a mob. This becomes extremely useful the further I venture in the game as I become increasingly ganged up on. Outside of battle, the drone aids exploration by acting as a flashlight in dark areas and scanning environmental elements for details, like deciphering mysterious wall symbols.

Keeping Players Engaged

Hell is Us is a promising confluence of ideas. I enjoy the blend of Zelda-like dungeons, Elden Ring’s sense of discovery, and detective-style investigations and puzzle-solving. Despite the game’s emphasis on providing a less guided experience, I felt little friction figuring out where to go and what to do. I chalk that up to playing an earlier section of the roughly 20-hour main story path (thorough players can expect to spend around 40 hours overall), but it also speaks to how Rogue Factor has carefully shaved opaqueness from its intentionally challenging puzzle design. This makes even the simplest problem-solving feel more rewarding.

After spending the last five years bringing Hell is Us to life, Belletête feels like he’s created the adventure of his dreams and is confident the team has at least a good game on its hands. Whether it’s a great game is up to players. But perhaps more than anything else, Belletête hopes Rogue Factor creates a consistently memorable and engaging experience.

“It seems like it might be the type of game, and these are the ones that I really cherish, that once you're done with a session – not done with the game itself, just the session's finished – you turn off your console, you turn off your PC, it stays in your mind,” says Belletête. “...it seems that maybe it's a game that seems to have that aspect, that when people stop playing, it lingers with them a little bit. And if it really does that, to me, it's amazing.”

Hell is Us launches on September 4 for PlayStation 5, Xbox Series X/S, and PC.

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0