South African AIDS Activist Pushes for H.I.V. Treatment Access After U.S.-Aid Cuts

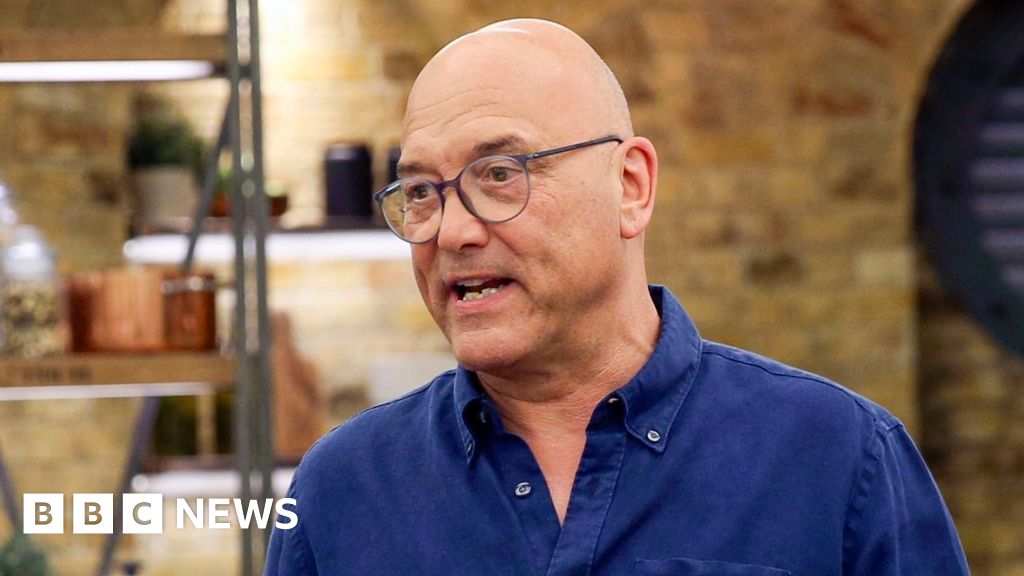

The activists gathered on the steps of the cathedral in the center of Cape Town. Most were older women, faces lined beneath their head wraps. They converged around a gray-haired man in an oversized coat, his shoulders hunched against the morning chill.

Linking arms, they set out to infiltrate a meeting across the street.

“Ready?” the man said, sounding a little weary, a little nervous.

It had been a while since Zackie Achmat confronted his government about matters of life and death.

Twenty-five years ago, Mr. Achmat co-founded what became the most powerful social movement in post-apartheid South Africa. He led a showdown against the government that won lifesaving medical treatment for millions of people with H.I.V. — and nearly killed him.

Until just a few months ago, Mr. Achmat, 63, thought those days were well behind him. He was spending time on a pomegranate farm, caring for rescue dogs and watching Korean telenovelas. He made a failed bid for parliament on an anti-corruption platform, but he was enjoying watching new generation of activists lead.

As for H.I.V., the issue that once dominated his life, he hardly thought about it. He didn’t need to, so robust was the national treatment program that grew out of the victories that Mr. Achmat and his colleagues won two decades ago.

Then came January, and the Trump administration’s decision to slash its foreign assistance, including funding for the President’s Emergency Fund for AIDS Relief, or PEPFAR. As part of an overall reduction in funds sent overseas, which Mr. Trump has called wasteful and a misuse of taxpayer dollars, PEPFAR’s budget has been sharply reduced.

South Africa received $440 million from PEPFAR each year, which paid the salaries of thousands of nurses, data managers and others who worked on the H.I.V. program. All of it was eliminated. The clinic in Cape Town were Mr. Achmat collected his medication closed overnight.

If any country is able to maintain H.I.V. services without U.S. help, it is South Africa. It has the continent’s most developed economy, and its government purchases most of its own H.I.V. treatment.

But in an eerie echo of history, the government has been near-silent about its plans, an approach that has stirred an old anxiety in Mr. Achmat and others, and spurred them into action once again.

In the first days after the cuts began, South Africa’s health minister, Dr. Aaron Motsoaledi, said that the government was making a plan, and that there was no cause for panic.

“Nobody must stop taking ARVs,” he said, referring to antiretroviral medications. “We will do everything in our power, because that will be dangerous for the individual and the country as a whole.”

But weeks passed, and Dr. Motsoaledi said little else.

Mr. Achmat and others waited to hear if the government would step in and reopen the closed clinics, create jobs for 15,000 health care workers who were paid by the United States, and put the vans that dispensed medication to sex workers and drug users back on the road. They expected a task force, like the team that the health ministry assembled during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Doctors, researchers and activists wrote open letters and demanded meetings with the government. Dr. François Venter, a veteran H.I.V. clinician in Johannesburg, wrote a widely circulated article titled “South Africa’s H.I.V. programme is collapsing — and our government is absent.”

Dr. Motsoaledi responded with a lengthy statement laying out reasons South Africa’s H.I.V. program was not at risk. The U.S. funds were just 17 percent of its budget, he said, and people who received health services from a U.S.-funded clinic could proceed to their local public one. He compared his critics to members of AfriForum — far-right Afrikaner activists who are widely reviled in South Africa.

So ended Mr. Achmat’s retirement.

That morning in May, Mr. Achmat gathered a small crew of veterans of his movement, the Treatment Action Campaign, known as TAC, to confront health officials holding a public meeting on tobacco policy.

“No placards,” he instructed. “We’ll do it nicely.”

They filed into a hotel conference room and found seats among members of Parliament and bureaucrats. Dr. Sibongiseni Dhlomo, a senior health department official, opened the proceedings, and as he began to speak, Mr. Achmat rose to his feet.

“Mr. Chairperson,” he interrupted, “We sent you a letter asking for a meeting. We haven’t heard from you.”

Dr. Dhlomo was affronted. “Enough,” he said. “We won’t allow it. You won’t disrupt this meeting.”

Mr. Achmat jolted as if he had been shoved. He erupted. “People are dying! If you had any respect you must listen to us.”

Dr. Dhlomo scoffed. “Those days are over.”

The women began to raise their fists, calling out “Amandla!” — a power-to-the-people chant from the apartheid era. The meeting became a melee. Parliamentarians bellowed for security. Mr. Achmat paced the length of the room, trembling with a rage that seemed to have transported him back 20 years.

Back then, Mr. Achmat was a veteran of the fight against apartheid, who had found himself in an unexpected new struggle.

He grew up in a colored township, first jailed and beaten for protesting white rule at 14. He became a zealous organizer for the African National Congress, the leading force against apartheid.

In 1990, as the country was beginning its transition to multiracial democracy, Mr. Achmat learned that he had H.I.V. The news landed like a death sentence. But it turned out that he was among the rare people whose bodies control the virus naturally for some time, so he threw himself into the work of building the new country.

It was a heady time, but the impact of H.I.V. was increasingly visible: Six hundred people a day were dying of AIDS.

In high-income countries, H.I.V. had become a chronic, not fatal, illness managed with medications. But in South Africa, treatment cost at least $15,000 a person a year, a king’s ransom. Speaking at a friend’s funeral, Mr. Achmat announced the start of the TAC, a movement to get access to affordable drugs.

It swelled with Black women from poor communities, who were galvanized out of secrecy and shame at their H.I.V. diagnosis. They targeted protests at multinational pharmaceutical companies, which blocked South Africa’s attempts to bring more affordable Asian-made versions of the medications into the country. Mr. Achmat was, by then, weakened by H.I.V. But he announced a drug strike: he would not take ARVs until everyone in South Africa could get them.

After a lot of bad publicity, the drug companies began to lower their prices in 2001.

But the government refused to buy the medicine.

Thabo Mbeki, who succeeded Nelson Mandela as president in 1999, championed the idea of African solutions for African problems. He began to question if drugs produced by big foreign companies were actually lifesaving. He surrounded himself with conspiracy theorists who said that H.I.V. did not cause AIDS, and he refused to provide the treatment through the public health system.

Bewildered but furious, Mr. Achmat and the TAC turned to civil disobedience tactics they had learned as foot soldiers for the A.N.C. — now using them against the A.N.C. itself. They were arrested in the thousands at sit-ins. And, using a tool of the new South Africa, they sued the government for access to lifesaving treatment.

Mr. Achmat continued his drug strike, growing sicker and sicker, and had to drag himself to give another speech or lead another rally. Mr. Mandela came to his bedside and entreated him to end his strike, and donned the “H.I.V. positive” T-shirt that Mr. Achmat had made famous, aligning himself with the protesters.

The Mbeki government lost in court and finally capitulated in the face of mass public pressure. In 2003, the national treatment program began. Mr. Achmat took his medication and within weeks had shed the chronic infections in his lungs and gut. He brimmed with energy.

And over the next 20 years, South Africa’s treatment program became the world’s biggest and one of the best run. In the first 11 years that the drugs were widely available, life expectancy rose by more than a decade . The activists of the TAC put away their signature T-shirts and moved on.

Until the announcement by the Trump administration. As public criticism mounted, Dr. Motsoaledi said that there were drugs on the shelves in public clinics — people needed only to go and collect them.

Public health experts were exasperated. They heard, in the government’s response, an echo of the Mbeki days.

“Why are we so embarrassed to say we need help?” said Dr. Glenda Gray, who oversaw a major H.I.V. research center that had lost a huge hunk of its budget, which had come from the United States.

The health minister’s office did not respond to interview requests.

On Wednesday, Dr. Motsoaledi announced emergency funding of $33 million for the H.I.V. program, about a tenth of what PEPFAR gave the country. He did not specify how it would be used.

It is difficult to know exactly what is happening to that program, because the ministry has not explained its plans and because so much of the data collection was U.S.-funded. Some people who used PEPFAR-run services have transitioned to the public system, which reported a rise in users, but it’s not clear how many. Tens of thousands of people have lost access to H.I.V. prevention as a result of the cuts. Testing rates have fallen, according to the National Health Laboratory Service.

However, Mr. Achmat’s angry declaration to the government committee — that people were dying — was exaggerated. Most clinics are still dispensing drugs, and while lines are long, and nurses are overworked, the program has not collapsed.

And yet the health ministry and activists are once again fiercely at odds.

Stephen Lewis, a Canadian diplomat who, as the United Nations’ special envoy on H.I.V./AIDS in Africa tried and failed to lobby Mr. Mbeki and became a champion of the TAC, said the response from Mr. Achmat and others was rooted in history.

“It’s not surprising that the activists are hyperbolic, harkening back to Mbeki, because there is tremendous anxiety — ‘My God, is it all going to happen again,’” he said. “In the middle of the night they’re haunted by the nightmare — the clinking of the bed frames as they pulled the dead out of the hospital wards.”

Mr. Achmat said he suspected they would need to use the courts — as they did 20 years ago — to force the government to engage.

His home is scattered with memorabilia, including framed newspaper cuttings of huge TAC demonstrations; he looks at them ruefully now.

“I can’t believe we’re doing this again,” he said. But he reckons he has a reputation for relentlessness that this moment requires. “If they see me,” he said of government officials, “they’ll shake in their bloody boots.”

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0