China Is Buying Appliances and iPhones. What Happens When the Subsidies Stop?

Browsing through the selection of Apple iPhones in an electronics store in Tianjin in eastern China, Zhan Demi rattled off the reasons she needed to upgrade her device.

Photos and videos of her toddler were quickly eating up her phone’s storage. One of her children’s teachers asked her to download various apps, again straining the limits of her device. But the factor that ultimately brought her into the store was a government trade-in program aimed at stimulating stubbornly sluggish consumer spending in China.

Confronting a trade war with the United States, China’s government has poured $42 billion this year into a consumer trade-in program, double last year’s amount. The aim was to jolt a much-needed surge in spending at a precarious moment for the economy by subsidizing discounts for a wide variety of consumer goods, from washing machines to electric vehicles.

The program has proved so successful that several municipalities have suspended or curtailed the program in recent weeks to prevent the money from running out prematurely. In May, retail sales grew a surprising 6.4 percent, exceeding economists’ expectations, spurred by robust demand for smartphones and home appliances.

“We want to shear wool from the sheep,” Ms. Zhan said, using a popular Chinese idiom for seizing an opportunity. She had already taken advantage of the program to buy an energy-efficient air-conditioner and other home appliances at discounts of up to 20 percent. “If we can upgrade everything at once when there’s a good deal, we’ll do it,” she said.

Tepid consumer spending has been a long-running concern for China’s economy. Chinese consumers save more and spend less than those in most developed countries, even when the economy is growing at a breakneck pace. But now that growth is decelerating, lucrative jobs are disappearing and the country’s slumping property sector — a key driver of the economy and an investment destination for savings — is showing no signs of rebounding, boosting spending is critical to sustaining economic growth.

China’s usual playbook for lifting the economy may not work this time around. It cannot spend as lavishly on infrastructure as it did in the past. Its local governments are swimming in debt after decades of building airports, train stations and bridges. Its continuing trade feud with the United States and a growing global concern about the flood of inexpensive Chinese goods limit its ability to rev up the country’s factories to increase exports.

In a reflection of the challenges facing policymakers, Ms. Zhan said that, despite spending through the trade-in program, she was also cutting back. When her preferred coffee shop raised prices to $2 a cup from $1.40, she decided to buy beans and make coffee at home. She said it was natural to make such choices when the economy was not good.

“Many people are even unemployed, or they are forced to stop working, or their salaries are cut,” Ms. Zhan said. “Consequently, rather than just being short of money, people tend to compare and make choices with more consideration.”

While the ruling Communist Party has paid lip service to the importance of boosting consumption for years, recent statements from top officials are growing more emphatic.

Last month, China’s premier, Li Qiang, said the country was “intensifying efforts” to expand domestic demand with special initiatives. Speaking in Tianjin at the World Economic Forum, a meeting of business executives, government leaders and experts, he pledged to make China “a megasized consumption powerhouse on top of being a manufacturing powerhouse.”

Xi Jinping, China’s top leader, pledged this year to “fully unleash” the country’s consumers to counter the impact of a trade war with the United States.

The current trade-in program — similar to America’s “cash for clunkers” initiative — started late last year. It initially applied to eight categories of home appliances and automobiles. The discounts range from 15 percent to 20 percent, with larger savings reserved for more energy-efficient products.

China, which issued special Treasury bonds to fund the program, allocated twice as much money for it in 2025 and extended the products covered to include smartphones, tablets and smartwatches.

Last month, the municipal government of Chongqing, along with a few other regions, halted the subsidies. Chongqing, a city of more than 30 million people, stated that the pause was not a complete cancellation but rather a preparation for a second round of subsidies that would be available at a later date.

Despite the success of the trade-in program, economists fear that its impact on consumption will be short-lived and could lead to a decline in the second half of the year and the first half of next year. Nomura, a Japanese investment bank, estimates that retail sales in the second half of 2025 will decline 0.4 percentage points from the same period last year, and by almost one percentage point in the first half of next year.

The government is exploring alternative policy options. Starting this year, China is planning to provide annual payments of $500 per child under 3 years old to families that have children, according to Bloomberg. Zichun Huang, China economist at Capital Economics, said the cash handouts were a “shift in mind-set” and laid the groundwork for other measures to support consumption.

Another factor contributing to China’s high savings rates is its sparsely funded social safety net. While most Chinese citizens are enrolled in medical and pension insurance, the benefits are limited and out-of-pocket payments are significant. Most people are not covered by unemployment or workplace injury insurance, including many of China’s 200 million gig workers.

Zhang Dylan, a salesman for the automobile maker BYD, said he had witnessed a modest bump in sales for cars from the trade-in program. As he sat waiting for potential customers to arrive, he noted that the demand, however, was nothing like it had been two or three years ago, when orders would roll in and there was a six-month waiting list for interested buyers.

Like many Chinese consumers, Mr. Zhang said he had experienced financial strain because of the real estate downturn. He and his wife bought a home in 2019 for about $265,000. Since then, its value has fallen by nearly half.

Asked why he thought Chinese consumers were not spending more, Mr. Zhang said people were being tightfisted because “it is too difficult to make money.”

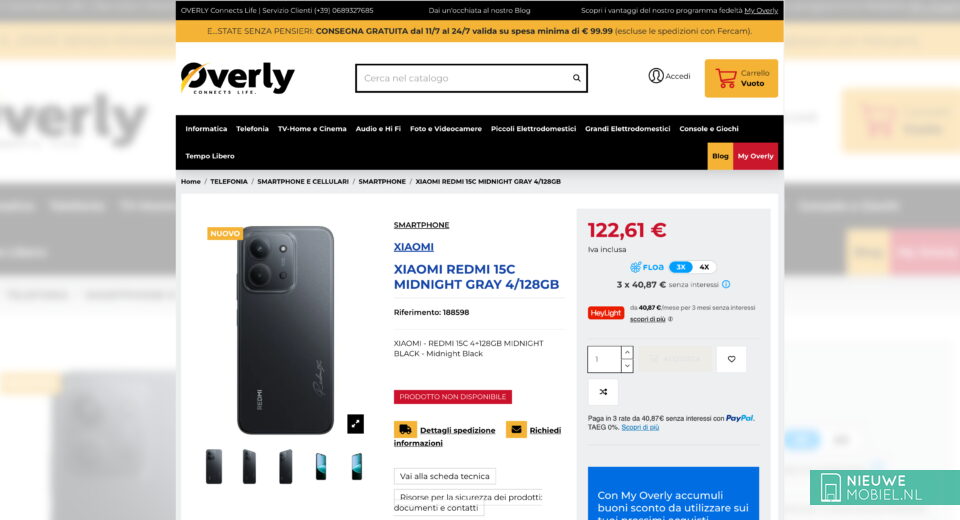

Inside a mall in Tianjin, Wang Mingke, a salesman at a store for the Chinese smartphone maker Xiaomi, said the trade-in program had spurred buying of the company’s smartphones. He said the store sold more than 30 smartphones a month, compared with 20 a month before the subsidies. A few months ago, in the early months of the initiative, the store sold 50 phones in a month.

Mr. Wang, 35, said the subsidy gave a little push to worried consumers to spend.

“Everyone is talking about the economic downturn, and earning money is indeed more difficult,” he said. “As your income becomes a little lower, when it comes to discretionary spending, you might just choose not to buy for now.”

Siyi Zhao contributed research.

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0