Baltimore Assessments Accidentally Subsidize Blight–and How We Can Fix It

One of the biggest challenges facing Baltimore is blight. For decades, the city has grappled with population loss, leaving behind thousands of vacant homes and empty lots that scar neighborhoods. These empty spaces not only serve as a constant reminder of visible decline, but also drain city coffers and undermine community safety.

Both the city and the state have launched ambitious initiatives to tackle this very problem. But what if the government’s own policies were quietly making the problem worse?

In our new report, published by the Center for Land Economics (CLE), we uncovered a fundamental flaw in how Baltimore’s vacant land is valued for tax purposes. Baltimore’s vacant lots are systematically underassessed to a degree that may amount to as much as half a billion dollars in undervaluation. This flawed methodology not only actively encourages blight, but also punishes development and unfairly shifts the tax burden onto ordinary homeowners and businesses. The good news is that these problems are correctable.

You can read the full report here.

Progress and Poverty is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Quick Note for Progress & Poverty readers

This report is the culmination of over many months of work digging into Baltimore assessments. The Center for Land economics got connected to Baltimore Thrive, an organization in Baltimore doing work to advance land value taxes, who raised concerns with us over local assessment quality issues.

At the same time, we were developing our open-source automated valuation method (AVM) software, OpenAVMKit, and so Baltimore became an early test case that helped shape our development process. That said, the content you will find in the linked PDF report ultimately represents just a small fraction of the analysis we performed.

Next week, we will be officially launching OpenAVMKit, the fruits of our labor these last six months as well as Lars’s years of experience in mass appraisal and land economics research. Our goal is to give researchers and assessors in both the private and public sector more power tools for real estate valuation, all in a standardized, transparent, reproducible, free and open source package. Furthermore, we want to improve the state of the art of land valuation in specific; in the coming weeks, we will share detailed updates on the technical question of land valuation specifically. Please subscribe to get notifications.

With that out of the way, onto a few findings from the report.

A Tale of Two Lots

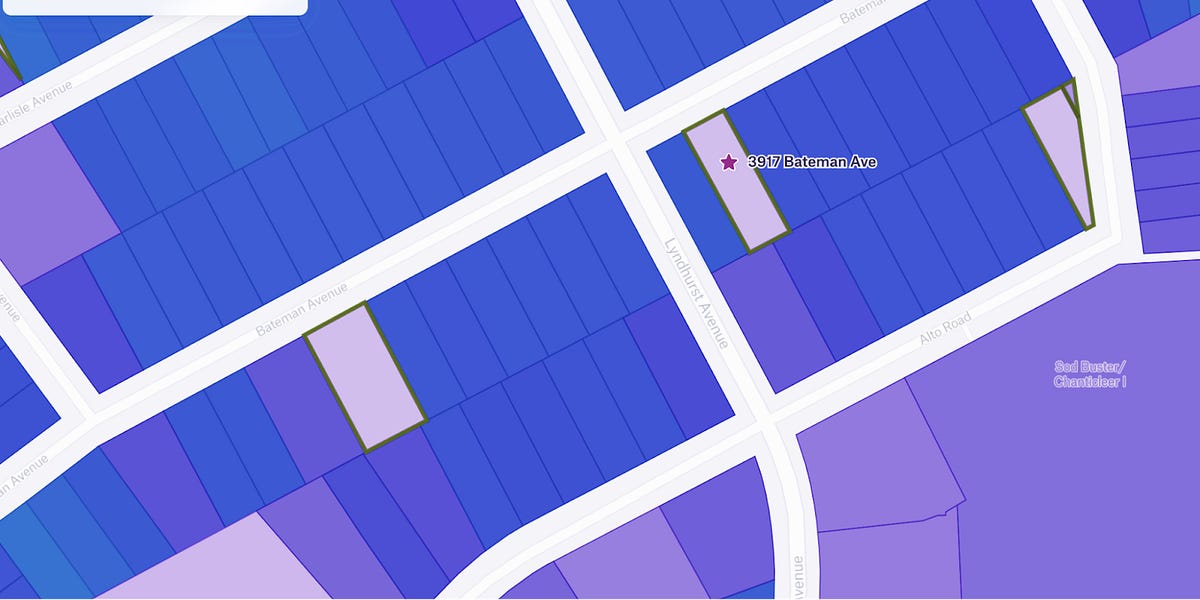

Let’s travel to the Windsor Hills neighborhood and look at a vacant lot at 3917 Bateman Avenue, sandwiched between two well-kept single-family homes.

In 2023, the Maryland State Department of Assessments and Taxation (SDAT), the agency responsible for valuing all property, assessed this empty parcel of land at just $7,500. That works out to about $1 per square foot (ppsf).

Now, look at the lots right next door. They’re the same size, on the same street, with the same access to utilities and amenities. SDAT values the land portion of each of these improved properties at an average of $8 ppsf. The vacant lot’s valuation stands out like a sore thumb—its assessed value is a fraction of its neighbors'.

So, which is it? Is the vacant land undervalued, or is the improved land with houses on it overvalued?

The market has already answered that question for us. On April 9, 2024, that "worthless" vacant lot sold for $50,000. That comes out to about $6.67 ppsf, over six times the assessed value, and much closer to the assessed land value of the homes next to it.

A Systemic Problem, Not a Fluke

This isn’t an isolated case. We found this pattern across the city. On a block of Whittier Avenue, developed rowhomes have land valued at over $11 ppsf, while the identical vacant lots right next to them are assessed at $1 ppsf or less, a 10x difference. A nearby vacant lot assessed at $1,800 ($1 ppsf) recently sold for $27,500 ($15.27 ppsf). When we analyzed all "prime" vacant rowhome lot sales (meaning, truly empty and developable land whose transaction records we were able to verify), the pattern became undeniable.

We compared the official assessed values to the actual market selling prices. If assessments were accurate, the ratio would be 1.0, or close to it. Here’s what we found instead:

For vacant lots that sold after their valuation was set, the median sale price was 8.33 times higher than the assessed value.

For vacant lots that sold before their valuation was set–ie, where the assessor had knowledge of the recent sale price before they made their assessment–the median sale price was still 2.84 times higher than the assessed value.

For every dollar of assessed value, these vacant lots sold for $2.84 to $8.33 on the open market. Both are statistically significant undervaluations.

This consistent undervaluation sends a powerful economic signal: keeping land vacant is cheap. It creates a massive tax advantage for owners who do nothing with their property, effectively subsidizing the speculative land banking that fuels blight. If you spend money developing a lot, your assessment and your tax bill suddenly jumps to match the neighboring lots, wiping out the tax break.

The scale of this problem is staggering. Baltimore has over 10,400 vacant parcels with a collective assessed value of over $327 million. One-fifth of this assessed value, or $66 million, is attributed solely to vacant land for parcels zoned for rowhome and single-family development.

Based on this observed pattern, we can set an upper bound on the error. That one-fifth of vacant land values in Baltimore, the residential portion, could be undervalued by as much as $484 million.

A Path to a Fairer System

Fixing this doesn't require a massive overhaul of the system. The core issue is that SDAT often treats land value as an afterthought, sometimes assigning flat nominal values, and other times assigning land value as a flat 20% of whatever each developed property's total value is. Both methods lead to the large side-by-side inequities we have seen.

A Simple, Short-Term Solution

Instead of relying on nominal values and rules of thumb, SDAT can use market evidence where it is available. We tested a simple model: a spatially weighted average. To value any given parcel, you just look at the prices of the five nearest vacant lot sales, giving more weight to the closest ones. It’s simple, transparent, and grounded in real market data.

As you can see below, this straightforward approach (right) tracks actual sale prices far better than the current assessments (left).

Using this method, we found that the undervaluation for vacant, rowhome-zoned parcels alone (which does not include vacant single-family parcels) is approximately $120 million.

Progress and Poverty is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

A Long-Term Strategy: Better Data

Ultimately, the best path forward is for SDAT to improve its underlying data collection practices. Our investigation found widespread problems that handicap any attempt at accurate valuation:

Tens of thousands of properties are missing basic data like building size, age, and condition.

Sales are frequently misclassified—sometimes foreclosures, etc. are treated as market sales, and often lots which definitely had buildings on them at time of sale are marked as "vacant lot sales."

There's no good system to track building depreciation or renovations.

Fixing these data issues and modernizing the Computer-Assisted Mass Appraisal (CAMA) system is essential for fair and accurate assessments for all properties.

By aligning property assessments with market reality, Baltimore can turn a system that subsidizes blight into one that encourages development. It would ensure that those holding land pay their fair share. This isn’t just an accounting fix; it's a critical policy lever to unlock Baltimore's potential, stabilize neighborhoods, and build a more equitable and prosperous city for everyone.

Greg Miller and Lars Doucet run the Center for Land Economics, an organization committed to better property tax policy.

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0