Trump Declares Dubious Emergencies to Amass Power, Scholars Say

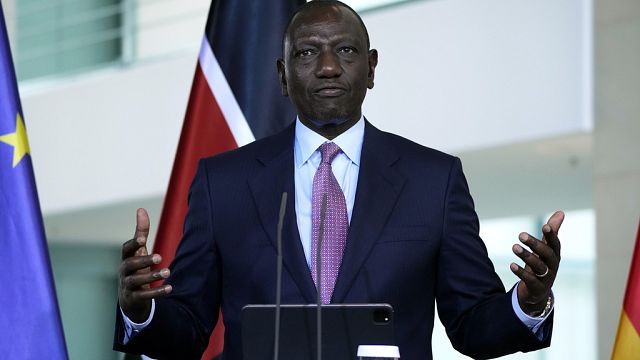

In disputes over protests, deportations and tariffs, the president has invoked statutes that may not provide him with the authority he claims. To hear President Trump tell it, the nation is facing a rebellion in Los Angeles, an invasion by a Venezuelan gang and extraordinary foreign threats to its economy. Citing this series of crises, he has sought to draw on emergency powers that Congress has scattered throughout the United States Code over the centuries, summoning the National Guard to Los Angeles over the objections of California’s governor, sending scores of migrants to El Salvador without the barest hint of due process and upending the global economy with steep tariffs. Legal scholars say the president’s actions are not authorized by the statutes he has cited and are, instead, animated by a different goal. “He is declaring utterly bogus emergencies for the sake of trying to expand his power, undermine the Constitution and destroy civil liberties,” said Ilya Somin, a libertarian professor at Antonin Scalia Law School who represents a wine importer and other businesses challenging some of Mr. Trump’s tariffs. Crisis is Mr. Trump’s brand. When he took office the first time, he promised to end “American carnage.” When he announced his most recent re-election campaign, he said he would reverse “staggering American decline.” Ever since he first ran for president in 2015, he has argued that only he can restore the country to greatness. Now in office again, he is converting that rhetoric into policy. Mr. Trump says that events and circumstances largely considered routine amount to emergencies that allow him to invoke powers rarely sought by his predecessors but embedded in statutes by lawmakers who wanted to ensure presidents could act quickly and aggressively to confront authentic crises. Frank O. Bowman, a law professor at the University of Missouri, said the laws Mr. Trump has invoked were premised on a presumption that the flexibility they granted would not be abused. “Genuine emergencies do occur, and Congress knows that it’s slow,” Professor Bowman said. “It wants presidents acting in good faith to move with rapidity.” But Professor Bowman said Mr. Trump’s approach was different. “Declaring everything an emergency begins to move us in the direction of allowing the use of government force and violence against people you don’t like,” he said. In a statement, the White House spokeswoman Taylor Rogers said that Democrats had failed “to protect Americans from economic and national security threats — inaction that has resulted in serious crises.” “President Trump is rightfully using his executive authority — as evidenced by many victories in court — to deliver resolve and relief for the American people,” she said. In fact, lower courts have for the most part rejected Mr. Trump’s assertions of emergency powers. In March, Mr. Trump invoked the Alien Enemies Act of 1798, which grants the president the power to deport citizens of nations engaged in war, invasion or “predatory incursion,” arguing that Tren de Aragua, a violent Venezuelan gang, was invading the United States. The law had been used just three times before, in the War of 1812, in World War I and in World War II. Several judges have now rejected the idea that the gang’s activities justified the use of the law. There is nothing in the 1798 law, Judge Alvin K. Hellerstein of the Federal District Court in Manhattan ruled last month, that “justifies a finding that refugees migrating from Venezuela, or TdA gangsters who infiltrate the migrants, are engaged in an ‘invasion’ or ‘predatory incursion.’” “They do not seek to occupy territory, to oust American jurisdiction from any territory, or to ravage territory,” wrote Judge Hellerstein, who was appointed by President Bill Clinton. “TdA may well be engaged in narcotics trafficking, but that is a criminal matter, not an invasion or predatory incursion.” One judge, Stephanie L. Haines, of the Federal District Court for the Western District of Pennsylvania, a Trump appointee, ruled the other way, saying the gang has engaged in a “predatory incursion.” Even apart from the 1798 law, Mr. Trump has embraced the rhetoric of a nation under siege, promising amid stepped-up ICE raids and violent protests in California to “take all such action necessary to liberate Los Angeles from the Migrant Invasion.” Mr. Trump used a similar justification for imposing tariffs in April, saying that “foreign trade and economic practices have created a national emergency.” Two courts have ruled against him, though an appeals court has temporarily paused the broader of the two rulings. California officials on Monday disputed Mr. Trump’s assertion that there was a crisis in the state that required an extraordinary federal response when they announced a lawsuit over his takeover of a unit of the state’s militia. “The situation in Los Angeles didn’t meet the criteria for federalization, which includes invasion by a foreign country, rebellion against the authority of the government of the United States and being unable to execute federal laws,” state officials said in describing the suit. The Supreme Court has yet to weigh in on Mr. Trump’s recent assertions of emergency powers. In the past, the justices have at times been skeptical of such claims. They did not hesitate, for instance, to reject President Joseph R. Biden Jr.’s invocations of the Covid pandemic to take emergency actions. In 2023, the court ruled that Mr. Biden had overstepped his authority in canceling some $400 billion in student debt based on a 2003 law that gave the executive branch the power to protect borrowers affected by “a war or other military operation or national emergency.” In 2018, on the other hand, the Supreme Court upheld Mr. Trump’s travel ban from several predominantly Muslim countries, discounting his history of incendiary statements about the emergency the nation faced, one he said warranted a “total and complete shutdown of Muslims entering the United States.” In his majority opinion, Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. cited an immigration law that gives presidents the power to “suspend the entry of all aliens or any class of aliens” as they see necessary. The provision “exudes deference to the president in every clause,” the chief justice said. The court will soon rule on a case arising from an executive order issued by Mr. Trump seeking to do away with birthright citizenship for the children of undocumented immigrants and foreign residents. Though the court’s decision is not likely to reach the constitutionality of the order and will focus instead on the scope of the lower-court rulings blocking it, the order’s proponents have also invoked the idea that the president’s action was justified by an invasion. Judge James C. Ho, who was appointed by Mr. Trump to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit and has been mentioned as a candidate for the Supreme Court, wrote in 2006 that birthright citizenship “is protected no less for children of undocumented persons than for descendants of Mayflower passengers.” But in an interview in November, he seemed to recede from that view. “Birthright citizenship obviously doesn’t apply in case of war or invasion,” he said. “No one to my knowledge has ever argued that the children of invading aliens are entitled to birthright citizenship. And I can’t imagine what the legal argument for that would be.” Two notable provisions of the Constitution discuss invasions. One prohibits states from engaging in war “unless actually invaded, or in such imminent danger as will not admit of delay.” The other says that “the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus shall not be suspended, unless when in cases of rebellion or invasion the public safety may require it.” Stephen Miller, the White House deputy chief of staff and Mr. Trump’s top immigration adviser, said last month that the administration was considering suspending habeas corpus — the fundamental right to challenge government detentions. “That’s an option we’re actively looking at,” he said, adding, “A lot of it depends on whether the courts do the right thing or not.” (The overwhelming scholarly and judicial consensus is that such a move would require congressional action.) The court’s most significant ruling on a president’s emergency powers came in its 1952 decision in Youngstown Sheet and Tube Company v. Sawyer, which rejected President Harry S. Truman’s claim that a national emergency — there, the Korean War — allowed him to nationalize steel mills in the face of labor strikes. The decision included a canonical concurrence from Justice Robert H. Jackson, a touchstone that Supreme Court nominees routinely praise at their confirmation hearings. Justice Jackson wrote that the framers of the Constitution were wary of granting the president emergency powers. “They knew what emergencies were, knew the pressures they engender for authoritative action, knew, too, how they afford a ready pretext for usurpation,” he wrote. “We may also suspect that they suspected that emergency powers would tend to kindle emergencies.”

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0