The Renegade Richard Foreman

The Renegade Richard Foreman

Jennifer Krasinski

The mind is a supple, ever-changing thing. This is a fact, not a flaw. For the theater artist Richard Foreman, who died this past January at age eighty-seven, the time of thinking, of writing, of creating was always now. And now. And now. In a 1926 essay called “Composition as Explanation,” Gertrude Stein wrote: “Continuous present is one thing and beginning again and again is another thing. These are both things. And then there is using everything.” As a young artist, Foreman picked up Stein’s idea and chose to stand in the slipstream of the present. He set aside middles and ends—too artificial, too confining—preferring for his plays to channel the sublime havoc of being. As he wrote in 1972:

I want to be seized by the elusive, unexpected aliveness

of the moment.…

…surprised by

a freshness

of moment that eludes

constantly refreshes.

Between 1968 and 2013, Foreman made more than fifty productions for the stage. These were not plays in any traditional sense. Instead, Foreman created living works of art by “using everything” that a given moment in time brought to bear on his process. He began not with a completed script but with a raw running text, the lines of which he would assign during his monthslong rehearsals, arranging and rearranging his words, giving them to one actor then trying them out on another. (The published collections of his works are more or less transcriptions of the live shows, including dialogue and direction.) He built and rebuilt his sets, props, and costumes every day in his theater space.

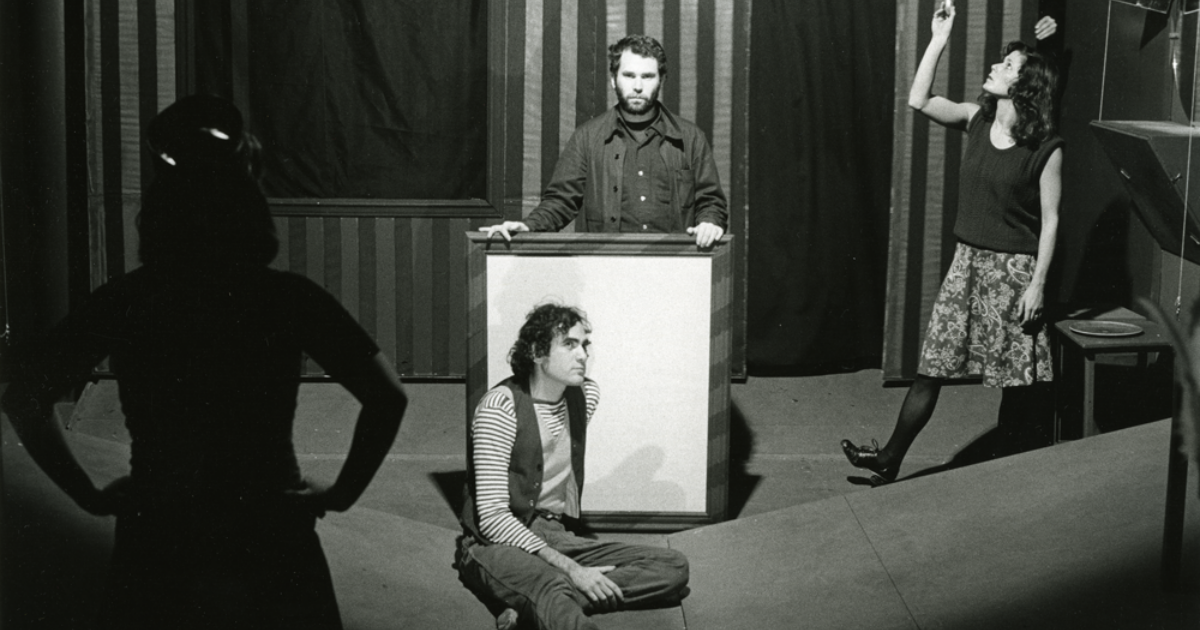

Foreman’s aesthetic changed over the decades. The visual style of his earliest works resembled that of the surrealists: he composed tidy, witty tableaux of odd objects and strange people speaking what often seemed like stray thoughts, all of which briefly shared the air before careening into their next encounter. Later, the look of his productions became more macabre, almost menacing: he would litter the stage with stuff, visual interferences that prompted the audience to lean closer and look harder.

Throughout, his plays remained fairly consistent, all running about seventy minutes and keeping his performers in a near-constant state of movement as they spouted lines that sounded as though a mystic had fallen through the looking glass or a philosopher had become stuck in a screwball comedy. These mind-melting, incandescent productions were equal parts theater, philosophy, literature, and visual art. They were also, by nature and by design, irreproducible, conceived as a different kind of cultural force. As Foreman described them in 1985:

A reverberation machine! That’s what my plays are!…The plays are about whatever happens when I am in a certain way, functioning on a certain level (which gives me most delight) and I open to you in that delight, my joy wants to amuse you with the fact that things inevitably will connect, will reverberate with each other. The world is a reverberation machine, that’s what I show you!

By the time Foreman died, he had figured out a way by which an artwork, and an artist, could remain in the present tense ad infinitum.

born in 1937, Foreman was adopted as a newborn by an affluent lawyer and his wife, who raised him and his younger sister in Scarsdale, New York. The suburb offered the boy almost none of the intellectual or cultural stimulation he craved, but it was only a short train ride to Manhattan, where he often sat in the audience for Broadway productions directed by the virtuosos of midcentury American realism, including Elia Kazan, Harold Clurman, and José Quintero. Foreman went to Brown University, where he made a name for himself as a gifted actor, and then earned an MFA in playwriting from the Yale School of Drama in 1962. Soon thereafter, he moved to New York City with his first wife, actress-turned-film-critic Amy Taubin, and quickly fell in step with the community of underground filmmakers and artists who orbited Jonas Mekas’s Film-Makers’ Cinematheque in SoHo, which gave a home to personal, lyrical films that often transgressed, or ignored, the usual conventions of cinema.

Foreman had long harbored inklings of ideas for a new kind of theater, or at least a theater that felt like his own, one that would shake both artists and audiences out of the comforts of outdated forms and what he felt was their stunting reverence for realism. After all, if it is commonly agreed that theater is a space of fiction, then why in the name of all that is sane would anyone demand that a play behave like real life? He would later recall that Jack Smith’s fantastical, orgiastic film Flaming Creatures delivered one of the great revelations of his artistic evolution. A brazen, no-budget, unabashedly queer bacchanalia inspired by Hollywood B-movie exotica, Smith’s 1963 magnum opus was unlike anything Foreman had seen before.

Downtown New York was then ground zero for the American avant-garde. The neighborhoods east to west below Fourteenth Street teemed with artists, writers, choreographers, dancers, composers, musicians, directors, and others who felt that art was not merely a profession but a way of being in the world, or of creating a new one entirely apart from the totalizing constraints of tradition. Foreman’s peers included the choreographers Yvonne Rainer and Trisha Brown, the filmmakers Mekas and Ken Jacobs, the theater artists Richard Schechner and Robert Wilson, the composer Meredith Monk, and, in the mid-1970s, Elizabeth LeCompte and the Wooster Group. When Foreman debuted his first play, Angelface, at Mekas’s Cinematheque in 1968 under the auspices of what would become his lifetime project, the Ontological-Hysteric Theater, he began by beginning again.

He rejected realism’s predictable logics, and also the false promise of using chance operations, the modus operandi of the composer John Cage and the Fluxus group of artists. He felt that each strategy too readily fulfilled an audience’s expectations rather than suspending them in time, manipulated viewers’ emotions instead of sustaining them with an ongoing supply of fresh food for the mind. In Angelface, for which there is no extant documentation save the script, Foreman presented rather affectless characters who converse about straightforward subjects like the movement and direction of their bodies with as much zeal as if they were talking to themselves. As he noted in his “Ontological-Hysteric Manifesto I,” written in 1972:

Art is not beauty of

description or depth of

emotion, it is making a

machine, not to do some-

thing to audience, but that

makes itself run on new

fuel.…

WE MAKE A PERPETUAL

MOTION MACHINE. (The

closer to that ideal the

better. Run on less and

less fuel…that’s the

goal of the new art

machine.)

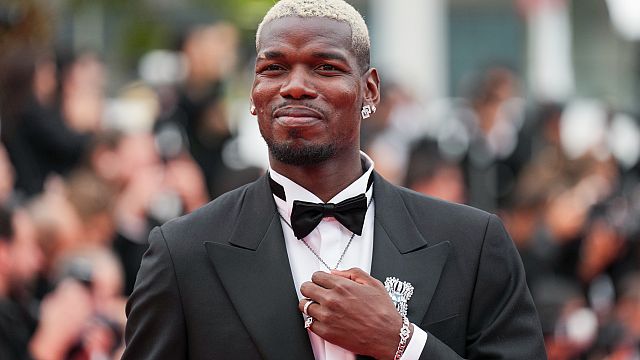

The analogy of artist and machine recurs in Foreman’s early writings, conveying the spirit of creating over and again without pausing to question why. The job at hand—thinking, making, performing—is the job at hand. Foreman himself could indeed seem like a machine. He wrote and directed at least one new play a year, designing the sets as well as the sound, which comprised densely layered loops and samples that he himself played live at every performance. Most of his works were staged in his loft at 491 Broadway until 1992, when he moved the Ontological-Hysteric to a small black-box theater at St. Mark’s Church in-the-Bowery in the East Village. He made a feature film, Strong Medicine (1981), starring the artist-performer Kate Manheim, his muse and second wife, with whom he collaborated on a number of his productions. He wrote operas and directed works (his own, and those of others) for the Public Theater, Lincoln Center, Paris’s Festival d’Automne, Los Angeles’s REDCAT theater, and many other venues around the world. Foreman was a MacArthur Fellow whose genius status did not prevent handfuls of people from leaving the theater at nearly every single one of his shows.

despite the machine metaphors, Foreman’s theater in fact worked as a container of consciousness. Like the human mind, subject to whim and distraction and desire, his plays were constantly interrupted, disturbed, even pushed to the brink of collapse. Foreman achieved this in part by using slapstick tricks: the lights would suddenly surge, or a deafening BANG would blast in through the speakers, or the actors would, on a dime, drop to the floor. No reasons given or allowed. He also made ingenious formal moves that were more nuanced, revealing their purpose over the duration of a show. He would hang strings across the stage, taut like lines drawn in the air, gently slicing into the room’s sight lines. A wall of plexiglass often stood at the foot of the stage, creating a fishbowl effect between the performers and the audience, though there was no telling who was in the drink and who was on dry land. At first sight, the plexi’s purpose seemed straightforward: here it was, the fourth wall made transparent. When Foreman’s actors would look at the audience, as they invariably did, the divide between stage and life was clearly maintained—here remained distinct from there—and yet all of us could see right through it. Then, when the lights would hit the wall’s surface just so, what the audience would see most vividly was its own reflection.

What were his plays about? Some people refer to writing as a practice. For Foreman, it was a lifestyle, a condition, an action born of physical leisure and a wandering mind. A day’s work might go something like this: He would read (ravenously) and doze off, keeping a pen and notebook nearby. When words or thoughts or half-thoughts trickled through his consciousness, he wrote them down, resisting the desire to muscle them into sense. He would then arrange his jottings into a text that seemed to him ready for staging. He often began his rehearsals without a firm idea about which character would say which line. Aiming to create a total experience of theater, Foreman demoted story. Instead, he’d plunk down on the stage characters who had questions, conundrums, impossible asks, then surround them with other characters who might, or might not, have answers. Repeated throughout his work—the shape that recurred—was the circularity of the search, of endless seeking. Although his characters never seemed to get the answers they wanted, by the time the show was over, his audiences were too giddy, too overwhelmed, to recall what had been asked in the first place.

Questions were important. Foreman’s plays sometimes began with a goofy one, as in My Head Was a Sledgehammer (1994): “Okay, Mr. Professor…are you as weird as I think you are?” Other times, Foreman launched a show with an equally goofy declaration. At the top of Film Is Evil: Radio Is Good (1990), for instance, Estelle says to Paul: “I have an announcement to make. You are not my Prince Charming.” Foreman’s productions could also be self-reflexive inquiries regarding the nature of theater, as in Eddie Goes to Poetry City, Part One (1990): “If this were a play, a curtain would be drawn. And the audience would be in darkness.” And as in Pearls for Pigs (1997): “I hate the actors who appear in this play.” A 1999 production cheekily announced in the first few minutes: “All audiences must now be informed that this play, Paradise Hotel, is not, in fact, Paradise Hotel, but is, in truth, a much more disturbing, and possibly illegal, play entitled—‘Hotel Fuck’!”

one afternoon in the summer of 1995, I received a call out of the blue while I was at work. “Jennifer, this is Richard Foreman. I’m calling to see if you’d like to be in my next play.” It was called Permanent Brain Damage. No audition, just a yes or no. I said yes, told him it would be my honor. He explained that his producer at the time, Sophie Haviland, would be in touch soon with the details, then said goodbye and hung up. I think our conversation, such as it was, lasted less than a minute.

I felt proud, excited, though I knew better than to feel flattered. Foreman had seen me in other plays at the Ontological-Hysteric, which Sophie had persuaded him to rent to young theater-makers when he himself wasn’t using it. There was no fooling myself into thinking that I’d gotten the job because of his high esteem for me as a performer, or his appreciation of any singular skills I may have had. I got the job because I, for reasons still unknown to me, fit his bill. (A year or so later, Foreman asked me to audition to replace the actress who originated the role of Columbine in Pearls for Pigs, which was about to go on tour. As soon as I’d finished reading—and I had done a pretty good job of it too, I thought—he explained that he couldn’t possibly hire me. I was too tall to fit inside the wooden box where Columbine had to hide at some point in the show, and there was no time to build a new one.)

Foreman alone knew what his shows should be, and that knowledge only revealed itself in the process of their making. I do not recall him ever presenting a sum-total vision of Permanent Brain Damage at the outset of rehearsal. No speech about its story, its themes, or any theories he was testing. He made no case for the work’s relevance or urgency or necessity, as theater directors often will. Doing so would have capitulated to the insidious belief embedded in the psyches of most American artists: that all works of art must be created in their own defense. Foreman had no doubts regarding his work’s right to exist—a confidence that emboldened his performers and audiences alike to stride into these unbalancing territories, to see for themselves—though he doubted every second that his work was working.

During the grueling, invigorating weeks of rehearsal, the Ontological-Hysteric felt more like an artist’s studio than a theater. Foreman always arrived in the morning before we did to tinker with the set, lights, and sound, and after releasing us for the day, he would stay to keep on tinkering. He had apprentices who built props on the fly or quickly mended and tweaked things onstage. I recall him once telling one of them to go out and buy newspapers and scatter the pages across the stage floor. On another day, he sent everyone home early because he hated something about the set, couldn’t stand the sight of it—was the back wall too far back?—and needed to fix it before he could continue. Over time, compositions (my word, not his) took shape. Instead of feeling like an asteroid colliding into the other performers, I saw our stage-size cosmos begin to hold together, to find its center by some rising force of gravity.

Foreman’s performers did not act in the traditional sense, serving instead as highly attuned instruments for the maestro. One of Foreman’s early influences was the great French filmmaker Robert Bresson, who referred to his actors as “models” and instructed them to repeat dialogue and actions until any whiff of theatricality, of self-consciousness, had dissipated. “What interested me,” Foreman wrote of his earliest productions, “was taking people from real life, nonactors, and putting them onstage to allow their real personalities to have a defiant impact on the conventional audience.” Eventually, that approach proved less interesting, and he realized he needed performers “whose skill enables the audience to look through them to see into the text itself.” In rehearsal, Foreman would have his cast repeat actions over and over again, which had the dual effect of dulling their nervous systems and pushing actions deeper into their bodies, transforming the actors into living conduits for his words. Whole afternoons might be spent on a thirty-second sequence, a week on a single scene. He wasn’t chasing an idea of perfection; he was writing the physical language of the play as it developed, move by move, which required time and testing.

Like a hawk hunting a field mouse, he had an attention for details so minute as to seem absolutely inconsequential. He might say to a performer something like: Sit in that chair and look to your left. Then cup your knees with your hands and slowly point your left index finger to the right. From wherever he was in the theater, Foreman would then train his eyes on the actor and correct or revise the gesture. No, go slower. Straighten your finger. Again. Now point with two fingers. The seeking and polishing might take just a minute or two, but sometimes it went on for a long time, the rest of the cast perched around the stage, watching, drifting. In rehearsals, boredom could be a near-ecstatic experience. One’s sense of scale shifted and warped as that tiny disposable gesture suddenly seemed as though it were the key to this great unknown work unfolding around us. For an audience, whose attention was invariably drawn in multiple directions all at once, such detonations may have gone completely unnoticed.

Being alive is a problem

Because being alive is an exception

To all other things.

the contradiction that kept Foreman’s work combustible had to do with his relation to context. An artist so devoted to the passing moment also instructed his audiences to “resist the present.” As he elaborated in his 1992 collection of essays and scripts, Unbalancing Acts: Foundations for a Theater: “You want to remove the hypnotic power that the world currently has over you. Rather than be hypnotized by it, you want to be free of the world. You want to realize that the world you see is made by the way you see it.” In other words, for Foreman, the choice is yours: what you see is what you make.

The true map of culture should be drawn like a bomb site or, more gently, like a stone dropped into water. At the center is the splash, from which the ripples radiate—reverberate. The wider their reach, the weaker the waves. The metaphor of the “mainstream” has always been faulty, if not altogether fatal, placing success stories at the center of the map—as determined by celebrity, money, broad appeal—and sidelining those artists, like Foreman, whose innovations are what made way for that success in the first place.

Foreman never wished to be imitated or reproduced, but he did want to ensure that he and his work could continue to reverberate. To do so, in the late 1990s, he began uploading to the Ontological-Hysteric website hundreds upon hundreds of pages of the raw texts from which he crafted his plays over the years, offering his writing for anyone to use for any reason: to stage, to revise, to cut up, to create something Foreman himself couldn’t have imagined. “I ask no royalty,” he explained in a note, hoping this would eliminate any barrier to any potential colleagues. “Because of the unique way I generate plays—this may mean I myself will still be using from this pool of material in the future. I invite you to do so also.” With this seemingly simple gesture, Foreman made sure that his work could remain in the present, even without him.

And that work is desperately needed. It is impossible to believe that the American mind is alive and thriving right now. Then again, belief, if not held lightly, can quickly become a palliative for one’s own lack of imagination. In the case of art and culture’s loss of life force, the depletion, which began long before 2016, can be traced beyond politics, self, and wealth to the disappearance of a rigorous, fortifying avant-garde.

What does it mean to be avant-garde? Experimental? To think about the world while thinking apart from it, creating not merely in resistance to its seductions and limitations, formal and otherwise, but free of them? Is it an ethos or a tradition? Yes and yes, although what complicates the sustaining of an avant-garde is its ambivalence toward legacy, something institutions seem to yearn for more than artists do themselves. In the spirit of the innovative, the inimitable, a gauntlet is dropped, surely to be picked up but not to inspire a line of gloves just like it.

Last autumn, I received a copy of a manuscript of Foreman’s unpublished works, which the poet Charles Bernstein was helping to edit when the artist passed away. In its pages, I read:

I have an

unquenchable hunger

for

true statements about

what it is to exist

(to exist is to- )

THE TRAP of existing.

Until the end, it seems, he was continuously beginning again.

The last quotation, from an unpublished manuscript by Richard Foreman, is used with the permission of the Richard Foreman Literary Trust.

Newsletter

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0