The messy reality of SIMD (vector) functions

| ONSITE VECTORIZATION WORKSHOPS AVX Vectorization Workshop at CppCon 2025, Sep. 2025, Aurora, Colorado NEON Vectorization Workshop at NDC TechTown 2025, Sep 2025, Kongsberg, Norway | You cannot attend? Register for an online workshop: More info… |

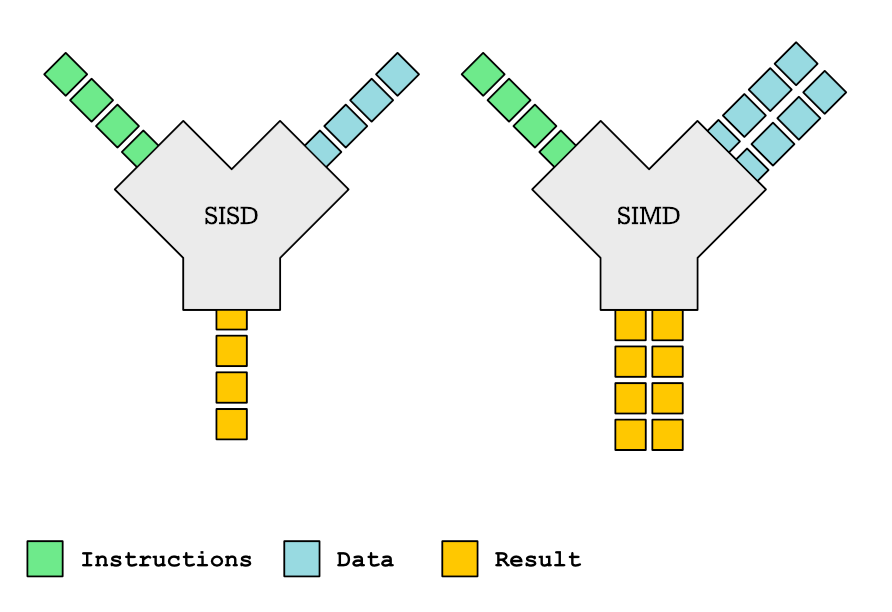

We’ve discussed SIMD and vectorization extensively on this blog, and it was only a matter of time before SIMD (or vector) functions came up. In this post, we explore what SIMD functions are, when they are useful, and how to declare and use them effectively.

A SIMD function is a function that processes more than one piece of data. Take for example a mathematical sin function:

double sin(double angle);

This function takes one double and returns one double. The vector version that processes four values in a single function would look like this:

double[4] sin(double angle[4]);

Or, we were to use native AVX SIMD types, it could look like this:

__m256d sin(__m256 d);

The basic idea behind vector functions is to improve performance by processing multiple data elements per function call, either through manually vectorized functions or compiler-generated vector functions.

Why do we even need vector functions?

The term vector function can refer to two related concepts:

- A function that takes or returns vector types directly (e.g,

__m256d sin(__m256d)). - An implementation of C/C++ functions which receives and/or returns vector types, and which the compiler can use during auto-vectorization (e.g.

double sin(double)can have several implementation. One implementation is a scalar, another can work with two doublesdouble[2] sin(double[2]), another with four doublesdouble[4] sin(double[4]). In an effort to vectorize a certain loop, the compiler will chose among one of those implementations.)

In this post we will talk about the second type of vector functions, i.e. vector functions that the compiler can pick to automatically vectorize loops. So, a compiler could take a following loop:

for (size_t i = 0; i < n; i++) {

res[i] = sin(in[i]);

}And call either the scalar version of sin or a vector version of sin – typically it will opt for vector version for performance reasons, but might also call the scalar version to deal with few iterations of the loop that cannot be processed in vector code.

Do you need to discuss a performance problem in your project? Or maybe you want a vectorization training for yourself or your team? Contact us Or follow us on LinkedIn , Twitter or Mastodon and get notified as soon as new content becomes available.

Declaring and defining vector functions

There are several ways to declare and define a vector function:

- Using custom compiler pragmas or function attributes. For example, GCC uses vector attribute

__attribute__((simd))to tell the compiler that a certain function has a vector implementation. - Using standardized OpenMP pragmas, such as

#pragma omp declare simd. OpenMP pragmas are generally portable.

There is a small difference if the attribute/pragma is applied to a function declaration or definition

- If put on a function declaration, tells the compiler that the function also has vector implementations.

- If put on a function definition, tells the compiler to also generate vector versions of the function.

So, a vector function could look something like this:

#pragma omp declare simd double sin(double v); // Works only on GCC __attribute__((simd)) double sin(double v);

Internally, most compilers treat OMP pragmas and their own internal implementation similarly. When using OpenMP pragma, you will need to specify a compiler flag to enable OpenMP, which for GCC and CLANG is either -fopenmp or -fopenmp-simd

So, if you are distributing your simd enabled library for other users to compile, and you cannot ensure -fopenmp-simd, the next best solution is to use compiler extensions with different extensions for different compiler. Here is how it is done by GNU C library:

#if defined __x86_64__ && defined __FAST_MATH__

# if defined _OPENMP && _OPENMP >= 201307

/* OpenMP case. */

# define __DECL_SIMD_x86_64 _Pragma ("omp declare simd notinbranch")

# elif __GNUC_PREREQ (6,0)

/* W/o OpenMP use GCC 6.* __attribute__((__simd__)). */

# define __DECL_SIMD_x86_64 __attribute__((__simd__ ("notinbranch")))

# endifWhat types of function parameters are there?

As we explained, if you want to declare a vector function, you would write something like this:

#pragma omp declare simd double sin(double v)

This is easy. The input is a vector of doubles, and the result is a vector of doubles. But consider a following function:

// In a flat image, sum all values in a column `column`

double sum_column(double const * const img_ptr, size_t column, size_t width, size_t height) {

double s = 0.0;

for (size_t j = 0; j < height; j++) {

s += img_ptr[j * width + column];

}

return s;

}The function takes a pointer to a flat image img_ptr with width and height, and sums up all the values in a column specified as parameter column. Imagine we want to write a vector version of this loop. In this context, a vector version could mean several things:

- A function that calculates 4 consecutive columns, e.g. columns 0, 1, 2, 3.

- A function that calculates any 4 columns using SIMD, e.g. columns 2, 11, 13, 4.

- A function that calculates a 4 sums for 4 different images , but the column is fixed.

What kind of function we need largely depends on the function caller. Here is an example of a caller:

for (size_t i = 0; i < WIDTH; i++) {

sum_columns0[i] = sum_column(img_ptr, i, WIDTH, HEIGHT);

}As you see, this corresponds to the case where parameters img_ptr, width and height are same for all columns, and the parameter column are N consecutive values (e.g. 0, 1, 2, 3).

For each parameter, except for the return value, we can specify what kind of parameter it is:

- variable, each lane

- uniform, each lane of the input parameter has the same value

- linear, lanes of the input parameter have linear values (e.g. 0, 1, 2, 3 or 0, 2, 4, 6)

It is important to tell the compiler exactly what kind of SIMD function you need, because the most flexible ones (where all parameters are variable) are also the slowest. Here is how #pragma omp declare simd looks for each of the above cases:

// A function that calculates 4 consecutive columns in SIMD, e.g. columns 0, 1, 2, 3. #pragma omp declare simd uniform(img_ptr, width, height) linear(column) double sum_column(double const * const img_ptr, size_t column, size_t width, size_t height); // A function that calculates any 4 columns using SIMD, e.g. columns 2, 11, 13, 4. #pragma omp declare simd uniform(img_ptr, width, height) double sum_column(double const * const img_ptr, size_t column, size_t width, size_t height); #pragma omp declare simd uniform(column, width, height) double sum_column(double const * const img_ptr, size_t column, size_t width, size_t height);

Apart from these attributes, which are the most important, there are a few others:

inbranch and notinbranch

To illustrate inbranch and notinbranch attributes, let’s modify our original loop:

for (size_t i = 0; i < WIDTH; i++) {

if (sum_columns0[i] == 0.0) {

sum_columns0[i] = sum_column(img_ptr, i, WIDTH, HEIGHT);

}

}In the original example, we called sum_column unconditionally, now we call sum_column only if sum_columns0[i] is true. Is there any difference with regards to vectorization?

The answer is, yes there is. In an example of vector functions working with 4 lanes, the original call to sum_column was calculating sum for all 4 columns, but in this example, we only calculate sum for some columns. In the context of vector functions, we need a mechanism to let our function know: don’t work on these lanes!

To do these, there are two attributes: inbranch and notinbranch.

notinbranchworks on all lanes unconditionally. Therefore, it is used in the context of no brancing.inbranchallows the function that know that calculations on some lanes are not needed. This is achieved using an additional parameter, the mask. If the lane X needs to be processed, then the bit X in the mask is set to 1.

Notice that if you don’t specify either inbranch nor notinbranch, then the compiler will expect both versions of the function to exist and will generate both versions of the function when applied to function definition. Here is an example of our sin function that can be used only outside of branch:

#pragma omp declare simd notinbranch double sin(double v)

Other attributes

There are two other attributes you can specify when declaring a vector function, for example:

aligned(parameter:value), e.g.aligned(img_ptr, 32)to let the compiler know certain parameter is aligned at a certain byte boundarysimdlen(value), e.g.simdlen(4)generates a function only with 4 lanes per vector. The parameter value should be a power of 2. If absent, it will generate functions for natural SIMD lengths. Example o natural SIMD length: a vector of doubles will have 2 lanes on SSE, 4 lanes on AVX and 8 lanes on AVX512.

Do you need to discuss a performance problem in your project? Or maybe you want a vectorization training for yourself or your team? Contact us Or follow us on LinkedIn , Twitter or Mastodon and get notified as soon as new content becomes available.

The reality of SIMD functions

While SIMD functions offer appealing performance benefits in theory, in practice, there are several limitations and caveats that reduce their effectiveness.

Limited compiler support

Not many compilers support vector functions. At the time when this post was written (July 2025), clang 20 doesn’t do anything with #pragma omp declare simd. GCC 15.1 does support it. This pragma is typically supported by compilers for the high-performance computing domain, such as Cray and Intel’s compiler.

Limited Usability

The reason for low compiler support for this feature is limited usability. What is exactly the problem SIMD functions are trying to solve?

If we had a regular function which is accessible to the compiler (e.g. it is in the header), then the compiler could easily inline that function in the loop that is calling it, and then vectorize the inlined version of the loop. After inlining, the compiler is free to do other optimizations (e.g. moving loading of constants outside of the loop). With calls to functions, such optimizations are not possible.

Function calls also have that negative property that the compiler doesn’t know what happens after calling them so it needs to assume the worst happens. And by the worst, it has to assume that the function can change any memory location and optimize for such a case. So it omits many useful compiler optimizations.

So even if you have a vector function, the autovectorizer will not use it unless (1) you use #pragma omp simd on the caller loop or (2) it is marked as const and nothrow, using GCC attributes. Here is the code:

// For the autovectorizer to vectorize the loop automatically

// either from the caller

#pragma omp simd

for (size_t i = 0; i < n; i++) {

res[i] = sin(in[i]);

}

// Or you need to define the function explicitly as nothrow and const

// (it's inputs depend only on the function parameters)

#pragma omp declare simd

__attribute__((const, nothrow))

double square(double x);

Compilers generate inefficient implementations

On GCC, a compiler-generated version of a vector function will very often just be a scalar version repeated N times. This is definitely not what we want!

Overwriting the compiler generated implementations

The biggest reason why we would want to use vector function is to provide a custom vectorized implementation of a scalar function using vector instrinsics. So, for example, we might want to provide a vectorized implementation of our sum_columns that handles four or eight columns in parallel. But there is no standard OMP way to do it, instead we need to dive deep into compiler’s manged names, vector ABIs etc. The rest of this post will be about that.

How to provide your own vector implementation using intrinsics?

As already said, there is no standard clean OMP way to provide your own implementation using compiler intrinsics. However, it is possible to.

Vector function name mangling

When you define a function a vector function, the compiler generates not one version of it, but several versions. Here is a snapshot from godbolt:

The compiler generated the original square(double), but also a few other versions. The versions that start with _ZGV are vector functions of the original square functions. This coding is standardized in the sense that all compilers produce the same function names. But function names on X64 and ARM are different. The full explanation of vector name mangling is available here, but in this post we will only go over the details you need to help you get started.

If we read the instruction manual above, the meaning of letters is as following:

- _ZGV – vector prefix

- b/c/d/e – the target ISA. The compiler has b is SSE, c is AVX, d is AVX2 and e is AVX512. As you can see, the compiler generates vector function for all possible architectures.

- N/M – N stands for non-masked and M stands for masked. Since we used

notinbranch, the masked version were not generated. - 2/4/8/16 – number of lanes in vector. Here, the compiler generated 2 lanes version for SSE, 4 lanes version for AVX and AVX2 and 8 lanes version for AVX512.

- v/u/l – for each parameter, there is a specifier which tells the compiler what kind of parameter is it: v is variable, u is uniform and l is linear.

Do you need to discuss a performance problem in your project? Or maybe you want a vectorization training for yourself or your team? Contact us Or follow us on LinkedIn , Twitter or Mastodon and get notified as soon as new content becomes available.

Overriding vector function

To overwrite a function, you should declare it with #pragma omp declare simd, but then, when defining it, you should define it without the pragma. Since the number of vector versions can be large, try using inbranch/notinbranch and simdlen parameters to limit the number of vector versions you have to maintain.

Let’s say I want to overwrite my square function declared like this:

#pragma omp declare simd __attribute__((const, nothrow)) double square(double x);

After this declaration, the compiler knows that a vector functions exist but it doesn’t know where to find them. If we try to link the program, the program produces an error:

$ g++ -g -O3 -DLIKWID_PERFMON -fopenmp-simd -ffast-math -mavx2 test.cpp -o test /usr/bin/ld: /tmp/ccIbzx6R.o: in function `main': 2025-07-simdattributes/test.cpp:42:(.text.startup+0xd7): undefined reference to `_ZGVdN4v__Z6squared' 2025-07-simdattributes/test.cpp:49:(.text.startup+0x137): undefined reference to `_ZGVdM4v__Z6squared' 2025-07-simdattributes/test.cpp:42:(.text.startup+0x247): undefined reference to `square(double)' 2025-07-simdattributes/test.cpp:49:(.text.startup+0x301): undefined reference to `square(double)'

So, the compiler was complaining about three missing functions: square(double), _ZGVdM4v__Z6squared (masked version) and _ZGVdN4v__Z6squared (non masked version). To resolve the issue, we need to provide the implementation of these functions but in another file!

If the compiler is not complaining about missing _ZGV functions, then the compiler is not using vector functions! See above how to force it to do this.

So, in C++, in a separate compilation unit, we are defining our vector functions like this.

double square(double x) {

return x*x;

}

extern "C" __m256d _ZGVdN4v__Z6squared(__m256d x) {

return _mm256_mul_pd(x,x);

}

extern "C" __m256d _ZGVdM4v__Z6squared(__m256d x, __m256d mask) {

__m256d r = _mm256_mul_pd(x,x);

return _mm256_blendv_pd(r, x, mask);

}

Note the following:

- The vector functions with prefix _ZGV are marked with

extern "C". This is necessary to prevent C++ name mangling. - The non-masked vector function takes one parameter, which is a vector of 4 doubles. The masked version takes two parameters, the second parameter is a mask.

If you are interested in all possible implementations for a function, copy the function to godbolt and check out what functions it defines. Example here.

Figuring out the parameters

In the previous example, the vector function had only one parameter, a variable double value. But what happens when a function has several parameters, some of them variable, uniform, linear?

Generally, variable parameters are passed in vector variables and uniform and linear parameters are passed in regular variables. So, a declaration with parameters like this:

#pragma omp declare simd uniform(img_ptr, width, height) linear(column) notinbranch __attribute__((pure, nothrow)) double sum_column(double const * const img_ptr, size_t column, size_t width, size_t height);

Will have a vector definition like this:

extern "C" __m256d _ZGVdN4uluu__Z10sum_columnPKdmmm(double const * const img_ptr, size_t column, size_t width, size_t height) {

....

}If your declaration has a mask because it is inbranch, then mask is the last argument of the call. So, a declaration.

#pragma omp declare simd inbranch __attribute__((const, nothrow)) double square(double x);

Corresponds to definition:

extern "C" __m256d _ZGVdM4v__Z6squared(__m256d x, __m256d mask) {

return _mm256_mul_pd(x,x);

}Another peculiarity: Let’s say you have a declaration like this:

#pragma omp declare simd simdlen(8) notinbranch __attribute__((const, nothrow)) double square(double x);

And you want to compile it for AVX. With AVX, you can hold 4 doubles in an 256-bit register. But the requested specialization is for 8 doubles in a single vector iteration, which means that the original value x will be held in two vector registers. The corresponding definition is like this:

struct __m256dx2 {

__m256d v0;

__m256d v1;

};

__m256dx2 square2(__m256d x0, __m256d x1) {

__m256dx2 res;

res.v0 = _mm256_mul_pd(x0, x0);

res.v1 = _mm256_mul_pd(x1, x1);

return res;

}Function inlining

You cannot declare and overwrite vector function in the same compilation unit. This means you need to keep declaration and definition separate, at least on GCC. Inlining is the mother of all optimizations, and it would be very useful to have it. You can however use link time optimizations to inline your custom vector function implementation. You will need to compile and link with -flto flag, but bear in mind that compilation and linking can take much longer with this flag.

Compiler quirks

When writing this blog post, I experimented a lot with GCC’s vector function capabilities, and this feature looks like far from perfect:

- The automatically vectorized vector functions can be very inefficient, even for very simple of cases. For example, masked version of our

squarefunction (return x*x) is a loop that iterates over the vector length and performs the multiplication. - GCC doesn’t generate vector calls if compiled when compiled with SSE4. Only AVX and later produce vector code.

- If you use

simdlen, the vector calls are omitted as well. In fact, it seems very easy to break vector calls.

Conclusion

Originally, this seemed like a nice and useful feature for a performance-concious programmer. It is even used in production namely in libmvec (vectorized math functions). However, getting the feature to work efficiently across compilers and environments can be challenging. This is unfortunate, given the potential value of the feature for high-performance programming.

Do you need to discuss a performance problem in your project? Or maybe you want a vectorization training for yourself or your team? Contact us Or follow us on LinkedIn , Twitter or Mastodon and get notified as soon as new content becomes available.

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0