What was Radiant AI, anyway?

What was Radiant AI, anyway?

A ridiculously deep dive into Oblivion's controversial AI system and its legacy

92 min read

Table of contents

The recent release of The Elder Scrolls IV: Oblivion Remastered has rekindled the public’s interest in the 19-year-old RPG classic, making it once again — at least temporarily — one of the most played and talked about Bethesda Game Studios titles. The remaster is a comprehensive upgrade of the original, featuring fully remade yet mostly faithful graphics, select gameplay improvements and a redesigned user interface. But it is still Oblivion, and I don’t mean that in the sense that it “maintains the spirit of the original game” or something like that. The remaster is quite literally built on top of the original game; the Oblivion from 2006, including its game engine and content, is still there, just with an Unreal Engine 5 wrapper handling the audio-visual side of things.

And that is interesting because Oblivion was a very ambitious game for its time. The world was huge, the graphics were cutting edge, but perhaps more importantly, it promised to deliver a dynamic and living world, with over a thousand fully voice-acted non-player characters (NPCs). The technology powering this was called Radiant AI, but it was too ambitious for its time and was mostly cut from the final game. Or maybe it was used in Oblivion, but Bethesda gave up on it before shipping Fallout 3 and / or Skyrim. Or maybe it was never really there in the first place, and Todd lied to us all along. What was Radiant AI, anyway?

This is a topic I’ve seen discussed in online spaces for quite literally decades, and the Oblivion remaster has brought it back into the spotlight once again among the terminally online. People mostly know it as the original Bethesda controversy; one of the first times BGS promised something they ultimately couldn’t deliver. However, very few people outside of the most hardcore fans and modders have even tried to understand it themselves. And by understanding, I mean the whole thing: why was it needed, what it was promised to be, what it actually was, and where it is now. This mammoth of an article (looks nervously at the reading time estimate) is my attempt to do just that.

This was supposed to be a short sidequest; a hopefully straightforward explanation of what Radiant AI is, and an opportunity to correct some of the popular misconceptions about it. But alas, things rarely are that simple. I’ve scoured through old RPG forums, fansites, modding tutorials and scans of early 2000s gaming magazines. I’ve spent maybe a couple dozen hours just exploring how Bethesda games work using their modding tools, from Morrowind to Starfield (which I had to buy just to check some facts). I even had to resort to reading the source code to the various script extender mods and DLL plugins — that’s how scarce the information is. Still, I don’t feel that I’m the most qualified person to write about this, as experienced Bethesda modders would have known a lot of this already. It is almost guaranteed that I got something wrong, so please @ me on Bluesky or elsewhere with corrections.

You can use the table of contents to skip to the parts that interest you the most, or just read it all if you have the time. Every heading is an anchor link, so you can also bookmark or share specific sections. Happy reading.

But before we can get to Radiant AI, we’ll have to go back to the island of Vvardenfell, where it all began. Well it didn’t really begin there, but let’s talk about Morrowind first anyway.

Video games from Bethesda Game Studios are known for many things: large open worlds, huge modding communities, mediocre combat systems, and of course, bugs. The Elder Scrolls III: Morrowind wasn’t the first game in the series — hence the roman III in the title — but it established many of the conventions that would define BGSFPRPGs for the next two (and soon three) decades. It was the first game to be built with Bethesda’s new game engine — a fork of Gamebryo, later rebranded as Creation Engine — which is still in use today, and brought the series into the hardware-accelerated 3D era. Morrowind pivoted from Daggerfall’s mostly procedurally generated world to a handcrafted one, which has arguably been the most important aspect of Bethesda’s games since then. It also had some of the prettiest water and sky effects of 2002, enabled by newfangled pixel shader technology.

But something was missing. Well quite a lot was missing — such as diagonal walking animations and a decent combat system, features which Bethesda games didn’t really have until Skyrim — but the most notable omission from a modern perspective was the lack of any kind of scheduled NPC behavior and / or non-combat AI. The denizens of Vvardenfell stand around night and day, rain or shine, waiting for the player to interact with them, like comically overworked employees of a depressing Disney theme park.

NPCs can be scripted to walk around aimlessly, or to follow the player or some other entity, but the system is so limited that to my knowledge NPCs that were placed outside can never enter a building, and vice versa. The characters usually have quite a lot to say, but they don’t really do anything unless the player (and / or a quest script) is involved. While Morrowind was groundbreaking in many ways, NPC schedules were already kind of a standard feature in some other RPGs, such as the Ultima series, Troika Games’ Arcanum, and the beloved eurojank classic Gothic.

But then everything changed with Oblivion.

I didn’t follow the pre-release hype for Oblivion (I was under 10 years old at the time), but from what I’ve gathered there was a lot of it. Oblivion was announced in September 2004 with a short statement on the official Elder Scrolls website, followed by a GameInformer cover story in October, which I was able to find on the Internet Archive. The 12-page article covered the game’s setting, new combat system and many of its new graphical features, accompanied by several unbelievably good-looking screenshots. Look at those trees, that grass, that lovely HDR bloom! Only next-generation consoles like Xbox 2 and Nintendo Revolution are capable of such a level of photorealism!

The article also covered the new AI system, though the term “Radiant AI” was not used yet. Here’s the relevant bit from the article:

The technology powering this next generation title is doing so much more than simply making everything look great, it’s also changing the rules of how virtual game worlds function. As mentioned before, the area of Tamriel that is the setting for Oblivion is populated with 1,000 NPCs. Unlike current games, these characters don’t simply disappear once the player leaves the area, they exist 24 hours a day, seven days a week. Every character has its own virtual life and its own schedule to follow.

Each of the 1,000 characters in the game is given a basic schedule of events to follow throughout each virtual day. They will shop, explore, eat, report for work, and more. However, while the characters are told what goals they need to accomplish, they are not told how to complete them. For example, a peasant who wants food may acquire it in several different ways. If the character has money, he will probably buy food; but if he is broke, he will try to obtain it some other way. He may go out into the forest to hunt, but hunting in the wrong place may get the guards on his case for poaching. So, the character may opt to steal food — he may even try to steal from you.

…

Guards will certainly be sent out after you if you scoff at the law, but you may also witness them hunting down an NPC who has committed a crime.

This bit is slightly less relevant, but you’ll find it funny if you’ve ever played Oblivion:

Interaction between the player and the virtual characters that populate the game is yet another area in which Oblivion is pointing towards the future of gaming. Characters will converse with one another in free-flowing, non-scripted discussions.

With articles like this, it’s impossible to know which statements are accurate representations of Bethesda’s claims, and which, if any, were inferred or even made up by the journalist. We’ll interrogate these claims later, but for now we can say that a large share of Oblivion’s pre-release hype originated from this article. It wasn’t the only one, though. Soon after the exclusive cover story Bethesda published more information on their website and did a round of interviews with various gaming media outlets. Here’s what they said about AI:

Oblivion features a groundbreaking new AI system, called Radiant AI, which gives non-player characters (NPCs) the ability to make their own choices based on the world around them. They’ll decide where to eat or who to talk to and what they’ll say. They’ll sleep, go to church, and even steal items, all based on their individual characteristics. Full facial animations and lip-synching, combined with full speech for all dialog, allows NPCs to come to life like never before.

I believe this is the first time the term “Radiant AI” was used publicly.

The second most important source of information (and hype) about the game and especially Radiant AI was the E3 demo in May 2005. Shame the gamma is completely off in the video — all the interior and nighttime scenes look like they were filmed in a dark cave — but this is the best quality version I could find.

Todd Howard: Our new Radiant AI system … allows NPCs to have full 24/7 schedules. These NPCs are not scripted. We give them general goals, and they figure out on their own how to accomplish them.

In the 6-minute Radiant AI section of the demo Todd Howard’s character walks through the city of Chorrol, overhearing a conversation between two NPCs (which is much smoother than anything that actually made it into the final game), and picks up a new quest. He then enters Renoit’s Books, gets an impossibly dynamic introduction from the shopkeeper, and plays a very early version of the persuasion minigame. Then more Radiant AI stuff happens:

Todd Howard: She (note: the shopkeeper) has decided she wants to practice her marksman skills, so she’s picked up a bow over here; she’s decided she needs ammo so she equips the quiver. And she can practice her skills; the same skill system governs her…. and she sucks. (In-game) Estelle Renoit: Terrible! Just terrible! I need a little pick-me-up. Todd Howard: And they’ll even detect potions in the environment if they need them, so she’s going to drink this potion, it’s going to increase her marksman skill; have the same effect on her that it would have on me if I drank it. It automatically raises her skill, and now she’s good at this activity, and that just works through the system. Estelle Renoit: That’s better!

Several more little things happen: Estelle picks up a piece of meat, feeds it to her dog, sits down to read a book, casts Paralyze on the dog, and sits down again for a meal.

Todd Howard: They’ll eat if they need to, how they get the food is up to them. They can steal it, they can buy it, they can grow it. Sleep when they want to.

Finally, she casts a fire spell to shoo the dog away and goes to bed. The demo moves on to the next section.

Many interesting things happened in the demo, and I’ll go through some of them in more detail later. Todd’s narration does kind of imply that the NPCs in Oblivion have needs and desires, and that they will autonomously try to fulfill them.

Bethesda conducted a total of three “fan interviews” (essentially AMAs of the era) on the official TES forums; one every year from 2004 to 2006. All three were organised by VP of PR Pete Hines with answers provided by creative director Todd Howard. The first one was on December 8th 2004, which I was able to find from the Internet Archive. It was also mirrored on Chorrol.com (named Waiting for Oblivion at the time), which is perhaps surprisingly still online.

Q: In regards to the new Radiant AI system, it has been stated that NPCs will be able to think and react independently of scripts. Does this mean that a player could order an NPC to do something (if in the position of a guild head, etc.), or perhaps find a random unscripted quest due to independent NPC actions?

A: Yes, we can do those things. I’m not saying they are in there, and we’re toying now with watching NPCs do things and how we can really get the player to affect that or have more fun with it, or even see it. So I won’t give specific examples right now, but we’ll be trying some similar things in places. I can tell you that our goal for the Radiant AI was the “Fargoth” quest in the beginning of Morrowind, which took some heavy scripting to get Fargoth to behave well, sneak around, steal the ring, put it in the stump, and such. Our early goal for the Radiant AI was that kind of thing just “happening”, without any scripting. And it works - which is great. But if we didn’t tell you what Fargoth was up to, you would have never noticed, or it would have looked really odd. Anyway, that’s the stage we’re at, we have the behaviors, and we’re trying to maximize the player’s perception of what’s happening.

Two more fan interviews were conducted in 2005 and 2006, the latter just before the game’s release. I couldn’t be bothered to find the original links to TES forums, but I’ll assume the Chorrol.com reposts are accurate.

- Fan Interview #2 (2005)

- Fan Interview #3 (2006)

Q: We’ve read that it’s possible for “friends” to join a faction along side you and you can watch them progress. Is this governed by RAI or is it a specific quest thing? Is it even possible to make friends like that?

A: Radiant AI is a global system that governs every action of NPCs. While we use it to do grand, overarching things like dictating how and where NPCs spend their days and nights, we also use it in much smaller sequences to do things as mundane as moving a character across a room to pick up an item. So, in a way, everything NPCs do is at some point governed by Radiant AI. In certain factions, you will meet what we term “continuing characters.” These are characters who you will come into contact with at several different points throughout the questline. You can talk to them, watch them grow, influence them, and perhaps even go on quests with them and alter their paths through the game.

Bethesda’s developers were surprisingly active on both their official forums and other communities leading up to Oblivion’s release, and Chorrol.com / Waiting for Oblivion gathered these quotes into one place. Unfortunately the individual quotes do not link to their original sources, so I can’t easily verify them, but there’s no reason for me to believe that they’d be fabricated.

- Developer Quotes #1 (2004 - February 2005)

- Developer Quotes #2 (March 2005)

- Developer Quotes #3 (April 2005)

- Developer Quotes #4 (May - August 2005)

- Developer Quotes #5 (September - October 2005)

- Developer Quotes #6 (November 2005 - January 2006)

- Offsite Developer Quotes #1

- Offsite Developer Quotes #2

- Offsite Developer Quotes #3

I’m surprised Bethesdians even bothered to answer some of these questions, as many seem like pure trolling not even worth a response. But there is good stuff too, such as an almost complete description of how Radiant AI works (in offsite quotes #1), which I will not repeat here, except for one important part:

Read a book on AI, and you’ll find things very similar to what we’re doing. The reason it’s AI and not scripting is because it uses goals and rules to determine how something is going to be accomplished. The designer establishes the goals, sets parameters (such as responsibility, aggression, confidence) on the actors, and leaves it up to the rules that have been established in the code to determine how the behavior plays out. It is most definitely artificial intelligence in the academic sense of the word.

Related to that, one of the developers (Steve Meister aka MrSmileyFaceDude) also directly addresses the E3 demo (in offsite quotes #2):

As far as the bookseller sequence. No, the entire thing was not scripted — not in the sense that it represents a designer typing in hundreds of lines of script code. In the sense that it’s a sequence of events that happen in a particular order, you might consider it scripted, but the way you set up those events, and how the actors accomplish them, is not scripted.

For example, the target practice. All she’s told to start practicing (basically) is “fire a certain number of arrows at this target from this location.” That’s it. There’s a bow in the room, so she automatically goes to get it first. There’s also a quiver in the room, so she goes to get that. She then equips the items, walks over to the firing point, and shoots a few arrows. The arrows miss the target not because she has been scripted to shoot at points away from the target, but because her marksman skill is low.

That’s the difference. She’s given a basic goal, and figures out how to accomplish it based on what she has available to her and her stats.

The sequence is a set of examples of the kinds of things you can do with RAI — including grouping a sequence of AI packages together to produce a tight, deterministic sequence of events.

…

The video is the same thing we showed at E3. It’s pieces & sections of existing game content and a lot of stuff made specifically for the E3 demo (for example, the entire sequence inside the bookstore — including all of the dialogue — was made for E3 in order to demonstrate some of the things you can do with RAI.)

We also have our first story about Radiant AI being “too smart” and causing problems (in offsite quotes #3, from Emil Pagliarulo):

Okay, here’s the thing with Radiant AI… If you ask, “Can the NPCs do this? Or can they do that?” They answer is yes, with RAI, they can do a ton of stuff. But the player is unlikely to see some of it for a variety of reasons. For example, if the player hits an NPC with a spell and they get poisoned, would the NPC try to purchase a cure posion potion? Well, no, not likely, because he’s going to be too busy trying to kill the player, and besides, the poison probably won’t last that long.

And, in some cases, we the developers have had to consciously tone down the types of behavior they carry out. Again, why? Because sometimes, the AI is so goddamned smart and determined it screws up our quests! Seriously, sometimes it’s gotten so weird it’s like dealing with a holodeck that’s gone sentient. Imagine playing the Sims, and your Sims have a penchant for murder and theft. So a lot of the time this stuff is funny, and amazing, and emergent, and it’s awesome when it happens. Other times, it’s so unexpected, it breaks stuff. Designers need a certain amount of control over the scenarios they create, and things can go haywire when NPCs have a mind of their own.

Funny example: In one Dark Brotherhood quest, you can meet up with this shady merchant who sells skooma. During testing, the NPC would be dead when the player got to him. Why? NPCs from the local skooma den were trying to get their fix, didn’t have any skooma, and were killing the merchant to get it!

…

Radiant AI functionality going haywire (like in the example of the skooma dealer being killed) — No, we haven’t removed any functionality. Those things are generally dealt with on a per-scenario basis. We’d tweak the NPCs, etc. to get the desired behavior.

There is this one bit of text about Radiant AI shenanigans I’ve seen repeated verbatim throughout the years, but it’s never attributed to anyone or any source, so I don’t know where it comes from. The oldest copy of the quote I could find is a post on TTLG forums in April 2006, just a couple of weeks after Oblivion’s release. Sorry for the wall of text; I promise this is the last long quote in this article:

Oblivion boasts a new artificial intelligence system, fully developed in house by Bethesda, codenamed ‘Radiant AI’. It aims to counter what was believed to be one of the major flaws of the previous installment (The Elder Scrolls III: Morrowind): the lack of ‘life’ of the NPCs in the game. Radiant AI gives every NPC a set of ‘needs’ (such as hunger) that they will need to fulfill, thus creating a more lifelike world.

Radiant AI works by giving NPCs a list of goals. Nothing else is scripted. They must decide how to achieve these goals by themselves based on their individual statistics. A hungry NPC might compare his current gold against his moral values to decide whether he will walk to a store and purchase food, or just steal it; a skilled archer can choose to hunt his own deer.

This has required massive testing, but has even greater long-term flexibility for future NPC AI as well as testing with PAC AI for further developments.

The following are examples of unexpected behavior discovered during early testing:

- One character was given a rake and the goal “rake leaves”; another was given a broom and the goal “sweep paths,” and this worked smoothly. Then they swapped the items, so that the raker was given a broom and the sweeper was given the rake. In the end, one of them killed the other so he could get the proper item.

- Another test had an on-duty NPC guard become hungry. The guard went into the forest to hunt for food. The other guards also left to arrest the truant guard, leaving the town unprotected. The villager NPCs then looted all of the shops, due to the lack of law enforcement.

- In another test a minotaur was given a task of protecting a unicorn. However, the minotaur repeatedly tried to kill the unicorn because he was set to be an aggressive creature.

- In one Dark Brotherhood quest, the player can meet up with a shady merchant who sells skooma, an in-game drug. During testing, the NPC would be dead when the player got to him. The reason was that NPCs from the local skooma den were trying to get their fix, didn’t have any money, and so were killing the merchant to get it.

- While testing to confirm that the physics models for a magical item known as the “Skull of Corruption,” which creates an evil copy of the character/monster it is used on, were working properly, a tester dropped the item on the ground. An NPC immediately picked it up and used it on the player character, creating a copy of him that proceeded to kill every NPC in sight.

Bethesda has been hard at work to fix these issues, balancing an NPC’s needs against his penchant for destruction so that the game world still functions in a usable fashion. In-game there are over unique 1,000 NPCs, not including monsters and randomly spawned bandits.

It doesn’t sound like an official statement from Bethesda, but more like a fan summarizing different stories they’ve read or heard somewhere. Other than the aforementioned skooma dealer example, initially I couldn’t find any direct quotes from Bethesda about other cases of Radiant AI misbehavior. However, I started digging through Internet Archive’s large collection of old gaming magazines, and I managed to find a few more examples.

In one interview with Play Magazine in April 2005, Todd Howard shared his surprise when Radiant AI caused an NPC to leave the building mid-fight to visit a nearby weapon shop for a dagger. Separately, PC Zone #165 from March 2006 featured an interview with Pete Hines, who said that while complex AI was important, they had to scale things back (like NPCs stealing from the player) to keep the game understandable; otherwise a player might assume their items disappeared due to a bug. The magazine’s following April issue then previewed Oblivion — it was already out, but paper-based magazines had long lead times — featuring a story about Radiant AI from an unnamed developer. This story closely matched the Skull of Corruption anecdote from the mystery quote, just without naming the item, and was followed up by this bit:

While it’s likely that such craziness will be removed from the final game for the sake of balance (unfortunately), it’s clear that Bethesda’s new Radiant AI system will still be very impressive.

So naturally the game shipped with the player-cloning exploit, and it even works in the remaster 19 years later.

While I wasn’t able to find sources for all of the Radiant AI examples, I think we can fairly safely conclude that this was indeed a fan summary of various stories and quotes from Bethesda and / or the press, probably originally posted to some forum that no longer exists. Some of the scenarios can still happen or could at least be implemented in the final game, but others sound like early ideas that were cut early — or were never even fully implemented. Mystery solved, at least partially.

Oblivion was released in March 2006 to almost universal acclaim and commercial success. It ended up becoming a generation-defining game, and is arguably one of the main contributors to why open-world games are still so popular today.

But there was some critique, as always, and it didn’t take long for the first complaints about Radiant AI’s shortcomings to appear. Even in Game Informer’s February 2006 preview article the author noted that the “complex AI governing their (the NPCs) actions wasn’t very overt”, and that he didn’t observe any behaviors like NPCs stealing food or honing their skills. The TTLG forum thread where I sourced the subject of the previous section was full of people wondering and arguing about the capabilities and limitations of Radiant AI, and how it compared to the E3 demo and other pre-release material.

Important and hopefully obvious disclaimer, because it’s 2025: Radiant AI has nothing to do with the current wave of AI hype. It has nothing to do with large language models, generative AI, neural networks or anything like that. While Radiant AI does utilize some ideas from classical artificial intelligence, video game AI is fundamentally about creating the illusion of intelligence; the goal is to make formidable foes and interesting characters, not to create a being capable of passing the Turing test. Think Pac-Man or Metal Gear Solid, not ChatGPT. Back to our regularly scheduled programming.

A cynical and / or pedantic take would be that Radiant AI was a nebulous marketing term that didn’t really mean anything specific. It’s something that you put in the game pitch deck on a slide titled “The three core pillars of the Oblivion experience” or something, and then later some poor sod had to figure out what the execs meant by that.

I think there’s an element of truth to that; Radiant AI isn’t really a specific game system or mechanic, but rather an umbrella term for all of the new AI features that were being developed for Oblivion. I’ve seen the persuasion minigame, the surreal NPC conversations (“I saw a mudcrab the other day”) and even combat AI being described as “Radiant” by fans and Bethesda alike, not to mention Skyrim’s largely unrelated Radiant quests. In my mind Radiant AI as it exists in the final game consists of three parts: the character system, the massively expanded AI package system, and the dialogue / conversation system. The AI package system is probably the most important one, so from now on when I refer to Radiant AI as a system, I usually mean “the thing that makes AI packages work”, unless otherwise specified.

Oblivion’s NPCs and creatures — collectively referred to as actors — are not too different from the player’s character from a game systems perspective. They have the same set of base attributes (strength, intelligence, agility, etc.) as the player, they have inventories and spell lists, and they can belong to factions. NPCs go further than your average cave bear or will-o-the-wisp; they have the same set of skills as the player (athletics, blade, sneak, etc.) and they actually use the armor and weapons they are carrying. Some creatures (such as goblins) also have the ability to use normal weapons and shields.

Every actor also tracks their disposition values toward the player and every other actor in the game world. It’s a number between 0 and 100 that determines how friendly or hostile the actor is toward the other party. Disposition can be gained and lost in various ways, but the most prominent one is through the goofy Persuasion minigame (“Don’t talk such rot!”). My understanding is that base disposition between any two parties is computed from faction memberships (e.g., guards inherently dislike members of the Thieves Guild), and then modified by various actions.

Actors have four more attributes (all integers between 0 and 100-ish) that exist solely for controlling AI behavior. These are:

Determines how low the disposition to another actor / the player can go before the actor becomes hostile. If it’s low enough, the actor refuses to fight even in self-defense; if it’s high enough, the actor will attack absolutely anyone —including their allies — on sight. Usually it’s somewhere in the middle.

Determines how low the actor’s health can go (as a percentage of their maximum health) in combat before they try to flee. Seems pretty straightforward, but it can also be used a bit creatively. As the wiki points out, the deer in the game have a confidence value of 0, meaning they’ll always try to flee any other actor they encounter regardless of damage taken, making them very skittish.

Least interesting and understood of the four attributes, which apparently affects how often the character moves while wandering around, and possibly something else as well. Next one, please.

This is the most interesting one, as it determines how much the actor respects the law. At 100, the actor telepathically reports any crime they witness to the guards — apparently including even when getting sneakily assassinated themselves. At 30 or lower the actor won’t snitch on your crimes, but more interestingly they will also commit crimes themselves to complete their goals — more on that in the next section. Low-responsibility shopkeepers also buy your stolen goods, which is how the fences unlocked via the Thieves Guild questline work.

If you aren’t too familiar with Oblivion’s internals, you might be wondering if I forgot about actors’ needs, such as hunger and sleep. After all, didn’t almost every pre-release article and interview mention or at least imply that characters have needs and desires, and that they will try to fulfill them? Well, yes and no. Oblivion’s actors do not have any needs in the same way as the characters in The Sims or Dwarf Fortress do. NPCs have schedules which usually involve at least sleeping and eating, but they don’t actually need to do anything to survive, and these activities do not affect them in any way. In this area, Oblivion’s characters function like typical video game NPCs, even though The Sims was named multiple times as an inspiration for Radiant AI.

All actors can be assigned one or more AI packages, and the same package can be assigned to multiple actors to re-use the same behavior. Each package is responsible for a single behavior or action at some time and with specific conditions — like wandering around the city market every day for 4 hours starting at noon when it’s not raining. Only one package can be active at a time, and the actor will automatically switch to the next one when the current one is finished or interrupted. AI packages weren’t used just for driving daily routines, as they are also very important for quests and other scripted events.

There is some documentation about the system in the unofficial copy / backup of the Oblivion Construction Set Wiki but it’s far from comprehensive, so I’ve had to figure a lot of it out myself by inspecting Oblivion’s game content in the Construction Set, doing some good-old-fashioned Googling and by building a test level to conduct deeply unethical experiments.

AI packages aren’t technically a new feature, as Morrowind had a very limited version of them. However, they are so much more powerful in Oblivion that it’s effectively a new system.

On a side note, the modding wiki is unofficial because Bethesda apparently shut down all of their official modding resources a couple of years ago, and all of the wikis are still down for “maintenance” at the time of writing — a bit odd for some of the most-modded games of all time. Things are even worse for Starfield, as from what I’ve gathered there’s literally no publicly available documentation for it at all. However, the Construction Set / GECK / Creation Kit tends to evolve quite slowly, and there are interfaces in the Starfield toolset that have remained largely unchanged for about 20 years.

Quick modding wiki rant

What an AI package actually does depends mostly on its type. There are several different types of packages, including but not limited to:

Makes the actor travel to a location, such as a specific (invisible) marker in the world, or to the nearest entity of a certain type (e.g., a bed or a chair). It doesn’t matter if the destination is in the same room or across the world, the actor will always try to get there.

Like traveling, but without a fixed destination. The most common application is to make an actor walk randomly around town or a dungeon. This continues until the scheduled time is over, or until the actor is interrupted by something else.

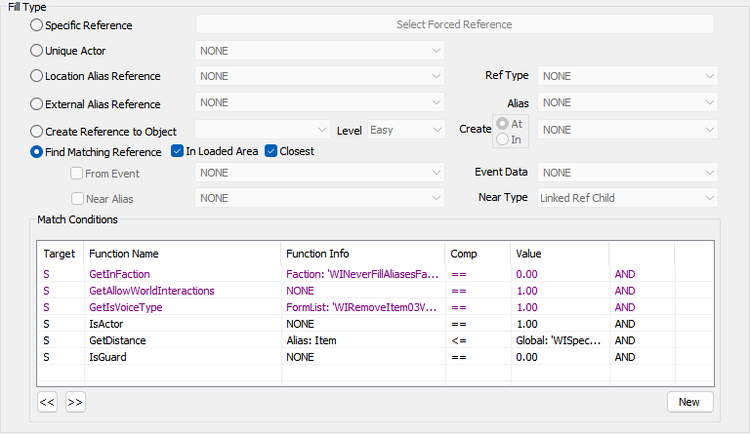

Now this is where it gets interesting. A package of this type makes the actor search some location for an entity or item of a certain type, such as a weapon, a piece of food, or a creature. “Search” is perhaps a slight misnomer, as the actor doesn’t actually go rummaging through potential containers, but rather immediately knows where the closest suitable target is and goes there. What happens next depends on the type of the target: items are picked up, enemies are fought, friendly people are talked to, and so on.

One creative use of this package is how hunters (like Imperial Legion Foresters) are implemented in the game. They don’t just wander around the forest (though they do that too), but they are configured to find venison. Deer just happen to have it in their “inventory”, so the hunter will seek them out, kill them, and then loot the meat. Theoretically if you dropped a piece of venison in the forest, at some point a hunter would find it and pick it up.

This is one of the package types which is affected by the responsibility attribute, which has pretty huge implications. If a character has low responsibility, it doesn’t really matter who owns the item they are looking for; they will just take it, even if it is in someone else’s pocket. Oblivion’s NPCs don’t seem to be very good at thieving, so they are almost guaranteed to get caught, especially when pickpocketing. Usually this results in the guards chasing the character down and then being given the opportunity to pay with their blood, unless they happen to carry enough money to cover the fine; NPCs can’t get arrested, so it’s either their money or their life.

I have a hunch that somewhere between 50 to 80% of all of the cool and weird Radiant AI stories were enabled by this package type, or any other package which internally makes use of the same behavior. As an example, the goblin war system seems to be largely powered by goblins using the Find package to navigate to the location of their sacred totem staff.

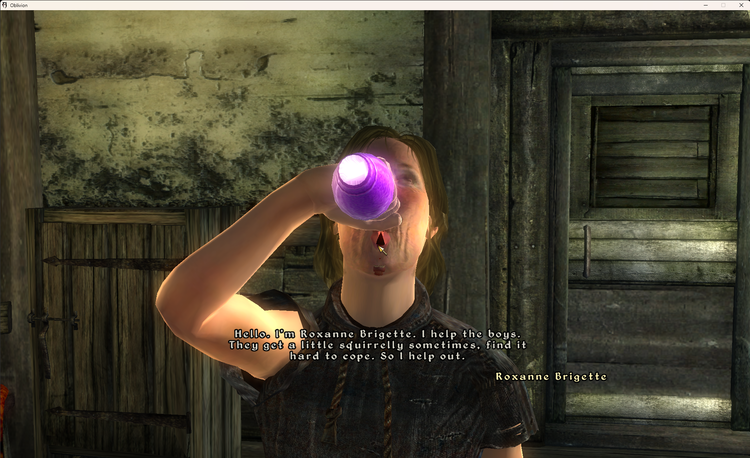

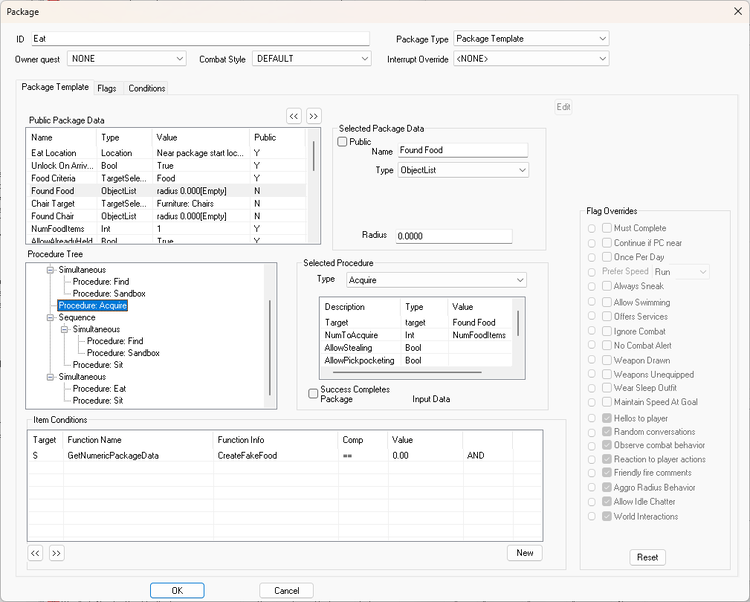

It’s like a combination of Find and Travel with a bit of additional logic. If the character isn’t already carrying food, they will search the designated area for a suitable item, pick it up, find a seat if one is available, and sit down to eat. The character actually consumes the food item just like the player would, which is how and why the Poisoned apple item works even outside of the Dark Brotherhood quest it was designed for. Responsibility affects this package type as well; low responsibility characters have no qualms about stealing food from other characters.

Makes the actor use an item from their inventory (or to find one nearby if they don’t have one) at the specified location. This can be used for various functional and purely decorative behaviors, such as making an NPC shoot arrows at a non-hostile target, to drink potions, or to make them play the animation associated with an item (e.g., reading a book or raking leaves). There’s also a very similar package type called Cast Magic, which as the name implies makes the actor cast a spell at some target.

In my tests, the package didn’t work quite as I expected. When an item of the target type was available, the NPC did acquire the item and use / equip it, but it did so by teleporting the item into their inventory. When the target is an item with an idle animation — such as a potion or a rake — the NPC doesn’t actually need the item if one isn’t available in the immediate vicinity, and will just play the animation with a nonexistent phantom item. You can probably pair it up with a Find package to make it behave more consistently. It was also easy to make the game crash to desktop when the parameters weren’t set up correctly.

You can probably guess what this does at this point. The actor finds a bed, either a specific one or the nearest one in a given area, and sleeps in it as long as the package is active.

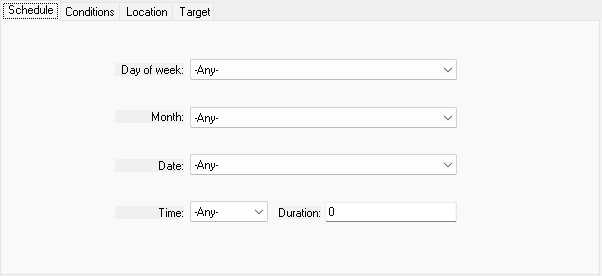

Each package has a schedule, which determines when the package can be activated. This is what powers NPC schedules in Oblivion and later games; for example, a character might have an Eat package scheduled at 8:00 AM for 2 hours, then a Wander package for the next 8 hours, then an Eat package again at 6:00 PM for 2 hours, and then a Sleep package for the rest of the night. Characters can and often do use different packages on different days of the week (like visiting a temple every Sunday — Oblivion is very Catholic), and a handful of NPCs even have scheduled packages for specific dates, like traveling to visit a distant city on the 16th of every month.

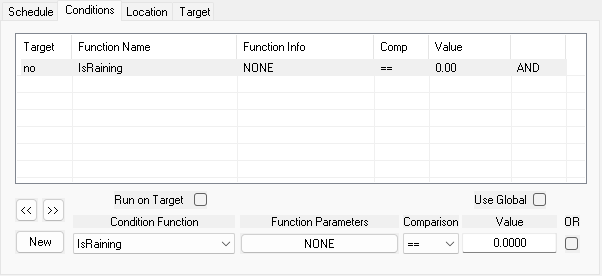

The schedule is accompanied by an optional set of conditions, which add further restrictions on when the package can be activated. Conditions are quite powerful, as they can test for various things about the actor, the target, the player and the game world. Each condition consists of a function, a set of arguments and a comparison to some constant value. Multiple conditions can be combined with AND and OR operators.

There are far too many condition functions to list them all, but here are a few of the most common ones:

- Check the distance to some entity; usually the player, but it can be anything.

- Check any actor’s race, sex, faction membership and other similar properties.

- Check if the current actor’s inventory contains an item.

- Check the weather, such as whether it’s raining or snowing.

- Check the time or date.

- Check the stage of a quest.

- Check a global variable.

- Or just generate a random number.

Finally, AI packages have a set of flags, and most of them have a location and / or a target. The flags are a set of boolean values that control various aspects of the package, such as whether the package can be interrupted, or if the actor is allowed to swim or ride a horse while traveling. The meaning of location and target depend on the package type, but usually the location is where the actor should go to perform the action, and the target is what the actor should interact with. For example, a Find package uses location to determine the search area, and the target is the item or creature the actor is looking for. Similarly, a UseItemAt package uses location to determine where the actor should stand while using the item, and the target is the item itself.

In most video games consisting of more than one screen / room, the game world only really “exists” around the player (if a digital space can be said to exist at all). When you start Half-Life 2, Dr. Breen is not sitting in his office waiting for your arrival, because that place does not exist until the game loads a level containing it. When you disembark The Platypus at the beginning of GTA IV and arrive in East Hook, while you might be able to see Algonquin’s skyline in the distance, chances are nothing else about that part of the city is loaded in memory: there are no pedestrians, no traffic, no street furniture, and so on. Usually this is not a problem as the experience would not really be any different even if those areas (that you can’t see) were populated, which is why almost every game does something like this as a very powerful performance optimization. This is enabled by several common game engine features, such as level of detail (LOD) optimization, culling and level streaming. Check the other articles in my blog for more in-depth explanations of these topics.

Bethesda’s games use many of the same techniques, for the most part. The world consists of hundreds of cells; small chunks of the world, consisting of terrain, vegetation, buildings, actors and other objects. Interior cells (buildings and dungeons) are loaded one at a time — which is why you have loading screens when entering and leaving buildings — while exterior cells are organized in a grid and loaded within a certain radius around the player. Cells further than a few hundred meters from the player are not loaded, and are instead represented by purely decorative LOD models.

What makes Radiant AI different from most other AI systems is that actors outside of the loaded cell(s) are still simulated, to an extent. Conceptually, this means that the game is simulating every actor in the world at all times; everyone goes through their routines even when you are not observing them. This is important for gameplay, because without something like it the characters would not be where you expect them to be when you return to a previously visited area; they would be stuck in whatever place and state they were in when the cell was unloaded.

In practice, when an actor is in an unloaded cell, their active AI package is processed in a much more simplified manner. Judging by the source codes of the EngineBugFixes mod and OBSE, AI packages have four different levels of processing: low, low-middle, high-middle and high. Characters in the currently loaded cell(s) use high processing, which is the “normal” level; that’s when AI packages do what they are supposed to do, and characters can engage in both combat and conversations. Lower levels are used for actors in unloaded cells. What the levels lower than high actually do is not publicly documented, but it’s pretty safe to assume that these lower levels use very coarse simulation, because most things actors would interact with — like beds, food items or even the whole landscape — are not loaded in memory.

My understanding is that one of the only package types that does anything meaningful at these lower levels is Travel, and even that is much more limited than it normally is. The comments in the OBSE source imply that pathfinding for low-level travel happens at the cell level: the game knows which cells are connected to each other, so it doesn’t need to load the terrain to figure out how to get from one cell to another. This is presumably combined with some magic constants to estimate how long travel should take, so that the game can teleport the actor to the next cell on the path when enough time has passed. I would also expect the fast travel system to estimate travel times in a similar way, but I haven’t looked into that.

This is a pretty smart way of doing things in a performance-sensible way, but it comes with obvious limitations. I have read some anecdotes from players of both Oblivion and Skyrim who claim that they’ve experienced characters dying to bandits or some other hazard while traveling on their own, but from my understanding of the system this is not possible. The low-level AI processing mode does not simulate combat or health, and as far as I can tell low-level processed actors cannot interact with each other in any way. And if my assumptions are correct, this architecture also means that low-level actors do not consume any actual food, not that it would matter.

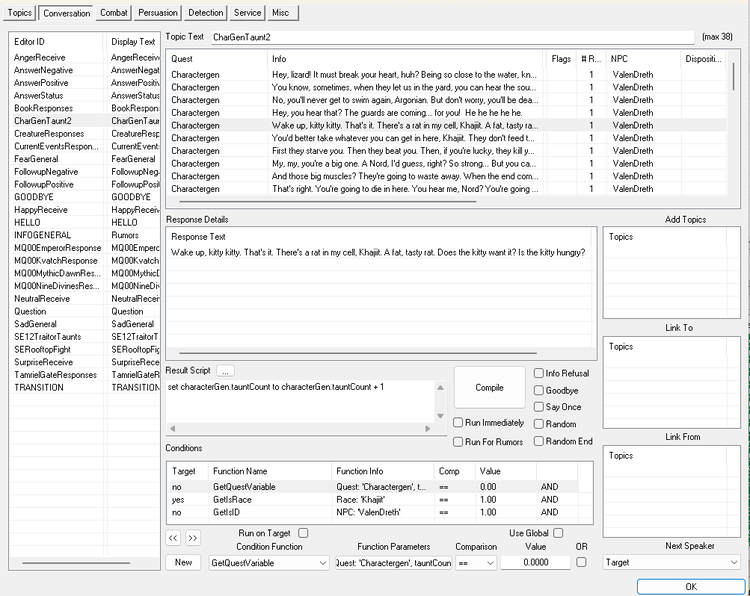

Finally, let’s talk briefly about the dialogue system, which could be considered a part of Radiant AI as well, since it was after all included in the Radiant AI section of E3 demo. Like AI packages, the dialogue system was also present in Morrowind and was expanded significantly for Oblivion. Even though from a gameplay point of view Oblivion’s dialogues are arguably much simpler than Morrowind’s walls of hypertext, Oblivion’s iteration of the system is much more complex and powerful, and used for more than just dialogue trees. The system also handles the wacky “Radiant” conversations between NPCs, the persuasion minigame, NPC greetings and other reactions to whatever is happening in the game world.

The dialogue system supports the same kinds of conditions AI packages use. This is what enables (some of) the dialogue in Bethesda games to be so dynamic and responsive — my mind immediately goes to guards reminding me to “take care with those flames” in Skyrim, when I have a fire spell or fire-enchanted item equipped. Oblivion’s very first dialogue after character creation is also influenced by this system.

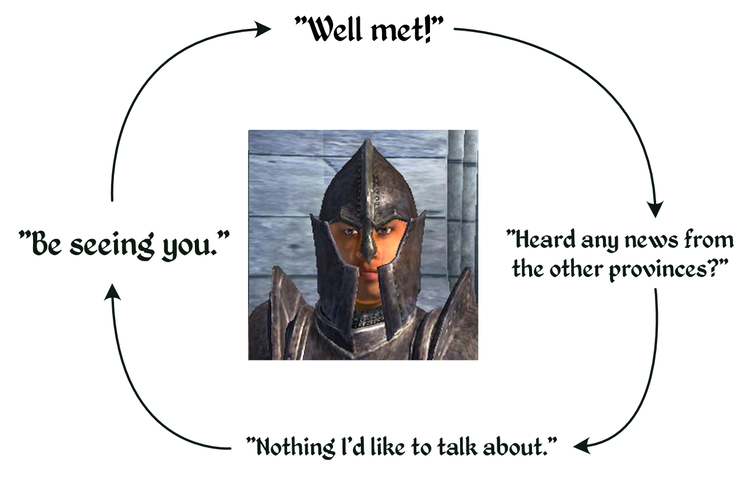

The NPC conversation system is basically a randomized auto-advancing dialogue tree, consisting of topics. Each topic can have several different responses, and most responses lead to a randomly selected follow-up topic. Conditions are used extensively to add new lines to the pool when certain quests are completed, or to prevent silly situations like an NPC telling a rumor about themselves. Did you know that the warmness of the greeting depends on the disposition between the two NPCs? Did you notice that NPCs say “good morning”, or that they point out if the other party has a disease?

This could be enough to make the conversations feel “free-flowing” and “non-scripted” as pointed out in the announcement article back in 2004, but unfortunately it’s not.

The problem isn’t really with the system itself, but rather with how it was used in Oblivion. For a game that can be played for potentially hundreds of hours, there just isn’t enough content to make the conversations feel interesting or relevant. Most conversation topics are not specific to one character or pair of characters, but rather shared between all characters in a city or even all of Cyrodiil. The most interesting parts of the conversation are the obvious bits of exposition that hint to side quests or interesting characters, but once you’ve heard them once, they become just noise.

Have a look at the E3 demo again, and try to ignore the silliness of the voices. The characters greet each other by name, they talk about a current event with more than a single line, and say a personalized goodbye when the conversation ends. This never happens in the final game outside of scripted quest dialogues. Apparently Bethesda had to limit the number and variety of voices and conversations because of a very boring reason: limited storage space of the Xbox 360 DVD.

Despite having over 1,000 NPCs, Oblivion was famously voice acted by a group that can fit quite comfortably into a single minibus, and generally speaking every race-gender combination has a single voice actor — and in some cases not even that, as Orcs and Nords don’t just share the same actors, but even the same voice lines. This was improved in the remastered version, which more than doubled the number of voice actors, but the actual written lines of dialogue are still the same, so you can now hear the same exact lines delivered by a larger group of actors.

My favorite piece of Oblivion trivia is also about the voice acting. The process of recording the voice lines was also, and this is a very technical term, batshit insane, as despite using the same voice actors for dozens of characters each, the lines were recorded in alphabetical order. Not grouped by character, not grouped by quest, just all lines beginning with “A” for potentially dozens of characters, and then all lines beginning with “B”, and so on. This is why some characters can have wildly varying voices between different lines.

Now that we understand what Radiant AI actually is, let’s recap what we’ve learned and go back to some of those pre-release claims and anecdotes to see how they hold up against the reality of the final game.

Verdict: Mostly true

Most characters do have schedules, but the complexity varies. Many characters do one or two things all day long, and never eat or sleep. Some characters (like most innkeepers) don’t have any schedules at all, which was probably done for gameplay reasons. Some schedules are completely broken without mods, as is tradition with Bethesda games. Having “one’s own virtual life” is dangerously close to being a philosophical question, but it’s at least a marked improvement over Morrowind.

Verdict: Mostly true

NPCs cannot buy from shops, but some NPCs have schedules that include regular visits to shops, where they’ll wander around for a couple of hours and then leave. Does that count as shopping? They do eat (although that doesn’t really matter), and there are some NPC adventurers who wander around dungeons.

Overall verdict: Technically true

The Eat package does make NPCs acquire food without specifying how they should do it, but in practice they will either seek out food items in the world, or disappointingly, they have an unlimited / respawning supply of food in their inventory. The vast majority of NPCs will always eat at the same location, which also implies acquiring food the same way every time.

Let’s tackle the food acquisition methods one by one:

Verdict: False

NPCs cannot buy food, or anything else for that matter. I was holding out hope that there would be at least one NPC in the game who has been scripted to buy something, but the GetGold condition function is used in only one AI package in the entire game, and even that is not really related to buying anything. The food in taverns and inns is free to take, so NPCs don’t need to buy it. I think you could implement this in the current system with an AI package and a custom conversation, but it would be very tedious to set up for more than a single NPC.

Verdict: False

As stated before, money doesn’t matter for NPCs. There are NPCs who do hunt (like the aforementioned foresters), but they don’t do it to acquire food; they just carry the raw meat in their inventory. There is no poaching for players or NPCs.

Verdict: True

Characters with low responsibility will take food from anywhere they can find it, including the environment and other characters’ pockets. In the final game there are only a few NPCs who actually do this, including the Argonian petty criminal City-Swimmer (who despite the name never swims) who is likely to die in a fight with the city guards before you meet her.

Verdict: False, but should be trivial to implement

NPCs cannot steal from the player, which Pete Hines confirmed before the game was released (and I did my own experiments just to be sure). This was done for gameplay reasons. With source code access (or reverse engineering experience) it should be quite easy to re-enable this, for whatever reason.

Verdict: Impossible in the final game unless scripted to do so

I was pushing an NPC for information, and when he wouldn’t cough it up, I attacked him, and he quickly ran out of the building we were in. This was not the expected behavior for this quest, as he was supposed to stay and fight. So I pulled up some debug information to see what he was doing, and he had left the building, went down the street, bought a dagger and ran back to fight me.

Let’s establish the parts of story that are still plausible in the final game:

- NPCs can flee from combat when their health is low (depending on their confidence attribute), and they can run to a different cell to escape. However, it doesn’t seem like this was a case of fleeing, as the NPC was supposed to stay and fight.

- Unarmed NPCs can pick up a weapon from the environment when they enter combat.

And that’s about it. Let’s see what doesn’t hold up in the final game:

- Once again, NPCs do not interact with the game’s economy. They cannot buy anything.

- Even if they could, how would an NPC know that the weapon shop — which is in a different, unloaded cell — contains weapons? I did a quick test with both a Find package (without specifying a location) and the usual “punch him in the face and see what happens” approach, and in both cases the NPC couldn’t find a weapon placed in a connected cell. If it worked like this, would it force the game to load the cell? If not, could this have been used to duplicate items?

This was Mr. Todd Howard himself about a year before the release, yet it still manages to sound like a made-up story. Maybe the capabilities of Radiant AI did really change radically so late in development — but I don’t think we have much other evidence to support that. Oh Todd.

A large chunk of the E3 demo — especially the bookstore scene — was created to showcase the features of Radiant AI, but it wasn’t meant to be taken as a literal representation of the final game, and I don’t know if the gaming audience of 2005 understood that. This shouldn’t have come as a surprise for the superfans who were following the development closely, as Bethesda developers were surprisingly open about this on various forums.

Of course the internet and games media were much more fragmented back then, so even though developers were posting quite candid comments about the development of the game, relatively few people would have seen it. There was no /r/GamingLeaksAndRumours back then, nor a cottage industry of gaming YouTubers dedicated to dissecting and sharing every single piece of pre-release material.

Let’s have a brief look at the demonstrated capabilities and some of the more specific claims made in the E3 demo:

Verdict: Depends on how you define “scripted”

I’ll just re-quote the relevant parts from Steve Meister:

As far as the bookseller sequence. No, the entire thing was not scripted — not in the sense that it represents a designer typing in hundreds of lines of script code. In the sense that it’s a sequence of events that happen in a particular order, you might consider it scripted, but the way you set up those events, and how the actors accomplish them, is not scripted.

The reason it’s AI and not scripting is because it uses goals and rules to determine how something is going to be accomplished.

The sequence is a set of examples of the kinds of things you can do with RAI — including grouping a sequence of AI packages together to produce a tight, deterministic sequence of events.

So, Bethesda’s stance is that something is “scripted” only when it was built with the engine’s scripting language. If we accept their definition, then yes, the E3 demo was not scripted. However, I would argue that AI packages and the conversation system are a form of scripting, albeit much higher-level and specialized than traditional scripting languages. There are conditions, loops (schedules) and side effects, and the conversation system can run scripts after lines of dialogue. And the events of these demos can only really happen in one specific order, so in that sense they are scripted as well.

Verdict: True for ambient conversations, but not in dialogues with the player

In the demo when the player enters the bookstore, Estelle greets the player and mentions that she was “just about to lock up the store”. Characters do actually lock their doors at night and when they leave their homes. The conversation system can query the current time of day and this is done for some things such as NPC greetings, but from what I can tell there is not a single NPC who changes their dialogue with the player based on the time of the day. So the engine supports it, but they couldn’t afford to record any additional lines of dialogue for a fairly niche feature.

Verdict: Up for interpretation, but mostly false

Characters don’t make decisions in the sense of weighing different options and choosing the one with the best outcome. They follow their schedules, and that schedule can include something that looks like training to the player. There are archers who shoot at targets and fighters who hit training dummies. Their skills never actually improve, which is probably a good thing from a gameplay perspective.

Verdict: False

NPCs do have the same skills and attributes as the player does, and they have at least some effect on their capabilities, but precision with ranged weapons doesn’t seem to be one of them. I conducted an experiment with my dear assistant Lex, and his accuracy with a bow was more or less equally perfect at Marksman 1 and Marksman 100, with a few complete misses — maybe characters adjust their aim to avoid hitting the player? I don’t know how the E3 demo was made; either accuracy used to be a factor but it was cut, or they faked it with a custom combat style.

Verdict: False

NPCs can be scripted to drink any potion with UseItemAt or the scripting language and it will have the same effect it would have on the player, but as far as I know they will never do it on their own. It is unclear if NPCs can autonomously drink health or fatigue restoration potions as apparently this capability was present in Morrowind, but I didn’t have time to test it.

Verdict: Could have happened pre-release, but not in the final game

Let’s have the quote again:

Funny example: In one Dark Brotherhood quest, you can meet up with this shady merchant who sells skooma. During testing, the NPC would be dead when the player got to him. Why? NPCs from the local skooma den were trying to get their fix, didn’t have any skooma, and were killing the merchant to get it!

That shady fellow is probably Nordinor, who is indeed a skooma dealer met during the Dark Brotherhood questline. There is a Skooma Den in the city, and it houses a group of low-responsibility addicts who are configured to consume skooma, and then head out to the city market to find more should they run out. There is something to this story: in theory, one of the addicts could encounter Nordinor in the market, try to pickpocket him to get some skooma, which would inevitably lead to a brawl that ends with someone dead.

However, there are several reasons why this cannot happen in the final game:

The fine folks of the skooma den have two AI packages: BravilSkoomaAddictSeek8x12 and aaaSkoomaAddictUse8x12. Both have the same suffix 8x12, which means that they are scheduled to run for 12 hours starting at 8:00 AM. The first package is of type Find, which is a known source of shenanigans. The second package, though, is of type Eat… does the game consider skooma to be food? I checked, and it does not. But when I enter the skooma den, all of the addicts immediately start drinking from their glowing skooma bottles.

Since the characters are not actually carrying any food, it seems that the only thing Eat accomplishes is to make the NPCs sit down on one of the chairs. When an NPC sits down, they select an idle animation to play, and there’s one in the game configured to trigger when an NPC has a bottle of skooma in the inventory. So, the drugs they are carrying are never actually consumed, which means they can never run out.

I validated this hypothesis by adding an extra effect to skooma to make it obvious when it is consumed. I started the game, entered the skooma den, and everything was like before. I changed the skooma again, this time adding the food flag, and re-entered the cabin.

The experiment was a resounding success.

Nordinor is one of the few NPCs in the game who sells skooma, so he would make a good target for the addicts. However, that skooma is not actually on his person. The way all vendors work in BGS games (at least up to Skyrim) is that every shop has a hidden container (usually a chest) somewhere in the world, which contains the shop’s inventory. Usually the container is in an inaccessible location, but sometimes the level designer makes a mistake and the vendor chest is actually accessible to the player.

What this means, though, is that the skooma addicts cannot actually steal skooma from Nordinor, because he doesn’t have any. The Find package won’t pick him as a potential “skooma container”, because the system doesn’t know anything about shops. Maybe he was actually carrying skooma back in 2005, who knows.

We already know that they don’t consume skooma, but let’s assume for a moment that they did. The addicts live in a locked cabin, so it’s unlikely for the player to enter it unless they are specifically looking for it. If the player never enters the cabin, the addicts should always remain in the low-level AI processing mode, and if my assumptions are correct, this means they would be very unlikely to ever consume a single unit of skooma during the average playthrough. It’s hard to be certain, though, as there is basically no documentation about the low-level AI mode. If you know, please share!

Quickfire round! As a reminder, these stories cannot be sourced to anyone at Bethesda, and have a high chance of being made up or exaggerated by the community.

Verdict: Plausible, though the language is imprecise

One character was given a rake and the goal “rake leaves”; another was given a broom and the goal “sweep paths,” and this worked smoothly. Then they swapped the items, so that the raker was given a broom and the sweeper was given the rake. In the end, one of them killed the other so he could get the proper item.

There is no package type for raking leaves or sweeping paths, but UseItemAt can be used to make characters play the rake and broom animations. UseItemAt by itself won’t cause the character to pickpocket the required item (at least in the case of a rake) so it needs to be paired up with a Find package. Do that for both characters, and with enough aggression and low responsibility they should fight over the items.

Verdict: Very likely made up

Another test had an on-duty NPC guard become hungry. The guard went into the forest to hunt for food. The other guards also left to arrest the truant guard, leaving the town unprotected. The villager NPCs then looted all of the shops, due to the lack of law enforcement.

There’s a lot of implausible stuff in this one.

- Guards do not become hungry, no one does. This could refer to a scheduled Eat package, but that would not be anything unexpected, just a normal part of the character’s routine.

- There are hunters, but no one hunts for food. Can be done, but this would be a very specific setup, and not a case of “unexpected behavior”.

- NPCs cannot be arrested. Even if they could, I don’t see how they could implement guards sometimes not following their orders without everything breaking down.

- The looting part is extremely unlikely. There is no way to check if a town is “protected” or not, and dishonest characters do not care about the presence of guards, they just steal whenever and wherever they can.

This story is either completely made up, or it’s from very early in the development when the AI system was still being prototyped. I’d lean towards the first option.

Verdict: Almost guaranteed to have happened

In another test a minotaur was given a task of protecting a unicorn. However, the minotaur repeatedly tried to kill the unicorn because he was set to be an aggressive creature.

I actually did this quest in Remastered just a short while ago. In the final version of the game the minotaur is indeed set to be aggressive, and the unicorn is not. The reason why they don’t fight is that they both belong to the same faction, DAUnicornFaction. Nothing to do with Radiant AI really, something like this could happen in any video game with multiple factions.

Verdict: See above

In one Dark Brotherhood quest, the player can meet up with a shady merchant who sells skooma, an in-game drug. During testing, the NPC would be dead when the player got to him. The reason was that NPCs from the local skooma den were trying to get their fix, didn’t have any money, and so were killing the merchant to get it.

I already covered this at length. This version of the anecdote differs slightly from the original version, because the original didn’t mention anything about buying the skooma even being a possibility. A classic case of a story gaining more details as it’s retold, perhaps?

Verdict: Can be reproduced even in the remastered version

While testing to confirm that the physics models for a magical item known as the “Skull of Corruption,” which creates an evil copy of the character/monster it is used on, were working properly, a tester dropped the item on the ground. An NPC immediately picked it up and used it on the player character, creating a copy of him that proceeded to kill every NPC in sight.

I tackled this briefly in a previous section, but in summary it is unquestionably true. A version of this story can be sourced back to Bethesda as it was told in an interview with PC Zone, though interestingly this version mentions the name of the item, while the PC Zone version does not, and that version also mentions that the reason for testing was physics sounds, not physics models. It’s possible that someone from Bethesda told this story multiple times, with slightly different details each time.

Let’s talk (hopefully) briefly about Goal Oriented Action Planning (GOAP), another approach to game AI from the same era that occasionally gets compared to Radiant AI. I have even seen some academic papers, or even worse, Reddit users, claim that Radiant AI is a variant or close relative of GOAP, which in my humblest opinion is not true.

I will not waste your and my time explaining GOAP in detail — for that you can read Tommy Thompson’s excellent article over at GameDeveloper.com, watch the video version or read Jeff Orkin’s original paper. Or if you are not allergic to mid-2000s C++, you can find most of F.E.A.R.’s AI source code from GitHub — remember when games used to have proper mod SDKs?

In short, though, GOAP is a planning-based AI architecture originally developed for Monolith’s horror FPS F.E.A.R. (2005). GOAP enables game characters to generate and execute multi-stage plans based on their current state and knowledge of the world. These plans are not pre-defined by the game designer, but rather get generated (or planned) on the fly using a system of goals and actions. Each goal has a priority (either static or dynamic), a set of preconditions that must be met before it can be picked, and some description of the desired world state that must be achieved to satisfy the goal. The system picks the most relevant goal for each character, and then tries to come up with a plan to achieve it. The actions have preconditions and effects (changes in world state), and they usually have an associated cost, which enables the planner to choose the most efficient (or the most fun) way to achieve the goal.

A hungry character could have the goal “be less hungry”. They don’t have any food nor any money, but they have the following actions at their disposal:

- Buy a frozen pizza

- Precondition: Has money, is in a shop that sells frozen pizzas

- Effect: Has a pizza, has less money

- Heat up a pizza in the microwave

- Precondition: Has a frozen pizza, is near a microwave

- Effect: No longer has a frozen pizza, has a hot pizza

- Eat the pizza

- Precondition: Has a hot pizza

- Effect: No longer has a hot pizza, is no longer hungry

- Do work (on a laptop that magically generates money)

- Precondition: None (in this example)

- Effect: Has money

- Travel between locations

- Precondition: None

- Effect: Is at a different location

With GOAP the planning system could generate a plan like this to satisfy the hunger goal:

- Do work

- Go to the shop

- Buy a frozen pizza

- Go home (where the microwave is)

- Heat up the pizza

- Eat the pizza, satisfying the hunger goal

I didn’t invent this example from nowhere: I actually implemented a version of GOAP back in 2017 for a university game development course, and the characters of the game did almost exactly that. The end result of two months of work was a weird mashup of The Sims and Roller Coaster Tycoon, involving egg-shaped little computer people with silly hats and facial hair. The blobular creatures lived in a single room, and used GOAP to maintain their primary needs: programming, fat, sugar and caffeine.

Implementing it was quite a challenge. It was too slow to run in the main thread, and I remember writing and debugging my custom thread pool / task system for Unity 5 (because it didn’t have any tools for threading at the time) for hours on end, because it suffered from constant deadlocks and other concurrency issues. I had to place strict limits on the complexity of the plans, because otherwise my system would consume gigabytes of memory for just a few characters in a small room.

Luckily these problems aren’t inherent to GOAP, and it has been used successfully in a number of games. It never became the standard AI architecture, though, and most modern action games are arguably still less advanced in the AI department than F.E.A.R. was about 20 years ago.

On a surface level, AI packages are largely equivalent to GOAP goals: eating, sleeping or finding 15 wheels of cheese are all goals that a character can pursue. The way Radiant AI selects the active AI package is also similar to how GOAP picks the next goal; packages are ordered by priority, and the system selects the highest priority one that satisfies the preconditions.

One could argue that AI packages are not really goals in the same sense as the ones in GOAP. Most types of AI packages do not represent a desired change in the world state; as stated many times before, eating or sleeping has practically no benefits for the character, so the planner in a “pure” GOAP implementation would never pick those actions. However, after watching Goal-Oriented Action Planning: Ten Years of AI Programming from GDC 2015, I don’t think that this makes a difference. The GOAP planner’s state doesn’t have to correlate with the actual game world; the state can include variables that only exist to guide the planner to pick a specific action. For example, it’s entirely valid to have a goal like Dance, and a planner state variable like hasDanced, which is set to true by the DoDance action. Most if not all games that utilize GOAP don’t just use it to make characters “play well”, but also to make them feel more alive and interesting by doing things that, from an objective gameplay-focused perspective, don’t really matter.

There is. however, at least one fundamental difference between Radiant AI and GOAP: Radiant AI is not based on planning. That might be a surprise to some; after all, Oblivion’s NPCs can demonstrably complete an AI package like Eat in a (small) variety of ways; the exact plan depends on the character and its environment. In reality, though, the AI packages are essentially pre-made plans that have some dynamic parts, but the overall structure is fixed.

Starting with Skyrim, Bethesda replaced the fixed set of AI package types with much more flexible designer-driven package templates. Strictly speaking the package templates already existed in Oblivion, but instead of being exposed in the engine toolset they were hardcoded into the engine. Each package template has an internal procedure tree, which defines which procedures (actions) are executed in which order, and under what conditions. Procedures are simple actions that a character can take: travel to a location, find all objects of a type in some radius, pick up something, attack someone, sit down, use an item, and so on. Practically everything NPCs do outside of (and potentially during) combat are just sequences of these procedures.

Being based on templates means that Radiant AI doesn’t involve any planning. This doesn’t mean the system is incapable of interesting behavior or fun gameplay, but the whole point of GOAP is that the designers don’t have to take everything into account; they provide the tools, and the planner figures out how to make the best use of them.

After looking into Radiant AI in depth, I was still wondering why there are so many people claiming that Bethesda games (namely Fallout 3) use GOAP. Some of those sources were quite obviously mistaken; attributing the classic Radiant AI myths to GOAP. But there were also some more credible-looking claims, and they must have come from somewhere. I did some digging, and I found at least one source: a 2009 article from the PC magazine / blog bit-tech.net, How AI in Games Works by Ben Hardwidge. Part 3 is about planning-based AI, and he interviews Bethesda programmer Jean-Sylvere Simonet about his work on Fallout 3’s combat AI. The development team redesigned the combat AI to be based on a planner, though to be pedantic — which I love to be — he doesn’t explicitly say that it was GOAP, but certainly something very similar.

So, while Radiant AI is not GOAP, Fallout 3 (and presumably later games) use a separate GOAP-like system for combat AI. Mystery solved.

It remains unclear how extensively Radiant AI really changed during Oblivion’s long development cycle and which features, if any, were actually “cut” before the game hit the shelves. Especially with the early marketing it’s hard to know which statements and claims were aspirational (“we want it to feel like this”) and which features they had actually implemented at some point, but couldn’t make them work in practice. Some, if not most, of the cuts were probably made for boring and solvable technical and gameplay reasons indirectly related to Radiant AI, such as limited storage space, development time constraints, performance issues, limitations of the animation system, and so on. The point about understandability Pete Hines made in one of the interviews is also very valid: if the AI system is capable of complex behaviors but other aspects of the game (such as graphics, sound, and user interface) cannot effectively communicate what is going on, then more advanced AI could in theory lead to an overall worse gameplay experience.

Even the E3 demo — which was presented about half a year before Oblivion’s original release date, until it got delayed by a few more months — makes some claims about features that the game arguably didn’t end up delivering on. For example, when Todd Howard said that the NPCs can “grow their own food”, did he actually mean that they would cultivate crops and eat them to survive? Or did he mean that there are NPCs who look like farmers, who spend most of their day playing a hoeing animation in a field, and then at dinner time eat one piece of bread from the infinite supply they have in their pockets? Is the difference between these two shallow imitations of life actually meaningful in a game which is ultimately about swordfighting with skeletons, and collecting flowers and bits of slain demons to make magic potions? I genuinely don’t know.

What we do know is that the content that exists in the final game does not utilize the system to its full potential, and there are probably many good reasons for that. Obvious performance and stability issues aside, even with my limited experience with the Oblivion Construction Set I can say that the user experience of the toolset does not really encourage the creation of complex and emergent AI behaviors. My PC has quite high-end hardware (including a Ryzen 7 9800X3D, one of the fastest CPUs on the planet) but the Construction Set is still very laggy and prone to frequent crashes, not to mention the multitude of interesting UI choices. Even though I could probably build a peasant-based Turing machine with those tools, I don’t think I would ever want to do that. Skyrim’s Creation Kit isn’t much better on that front, unfortunately, and the one from New Vegas is probably the worst of them all. That hasn’t stopped these games from being some of the most-modded of all time, but I would hazard a guess that it had some influence on the design decisions made during development.

And to be honest, the fact that Bethesda ended up using Radiant AI less ambitiously than originally planned wasn’t necessarily a bad thing. While we ended up receiving a great game, it’s also very buggy, goofy and unpredictable. I can imagine that if the game relied more on simulations and emergent gameplay, the end result could have been even less coherent and playable than what we got. The version we have now is kind of in a sweet spot: it’s funny and weirdly charming, without being completely broken. Well it is still very broken, especially the level scaling, but that’s largely unrelated to Radiant AI.

Check out Bacon_’s YouTube channel for more hilarious certified Bethesda moments.

There’s a fairly common misconception online that Bethesda gave up on Radiant AI after Oblivion, and that it was never used in any of their later games. This is not true; Radiant AI consists of multiple different systems that have their roots deep in the game engine, and a large share of them are still used in even the most recent Bethesda games. But what has definitely changed since Oblivion is Bethesda’s philosophy regarding emergent behavior and gameplay.

Fallout 3 was released a few years after Oblivion, and it didn’t stray too far from its predecessor, both in terms of technology and game design. Most NPCs have schedules, and there is even some variety depending on the weekday, which is a bit of a surprise considering the post-apocalyptic setting. Characters still have randomly generated discussions, but they are thankfully used in a more tasteful way. NPCs still find and consume food items, even when players don’t want them to.

Perhaps the biggest addition to Radiant AI was the new Sandbox AI package, which is basically an evolved version of the Wander package from Oblivion. It makes characters wander around in a specific area, and they can autonomously interact with the environment, such as sit on chairs, eat food, or (starting with Skyrim) work at a crafting station like a forge or an enchanting table. This makes it easy to add basic behaviors to characters without having to design an involved schedule for them. I’m in two minds about this: using Sandbox ensures even the less important characters do something instead of just standing around, but it also runs the risk of making everyone feel a bit generic.