What is gVisor?

It has been a really long time since I last wrote something here as life happens, things get busier, etc etc. I am now trying to get back into writing things down and here we go!

So, imagine a tool or a service that allows you to run some arbitrary code via a shell. Either through a ssh or more commonly, via a web terminal. How does these tools isolate your code from other people’s code and vice versa ? How come you cannot see other people code or processes ?

The first thing you probably be thinking, in 2025, is “Docker”. Each console must be running in their own container, right ? Very likely that you are right. That’s what I’d think too.

But, if these containers are all sharing the same operating system kernel, is that always sufficient, especially for untrusted code.

Let’s briefly revisit how standard Docker containers operate and interact with the host system.

(Image from Understanding Docker Architecutre)

(Image from Understanding Docker Architecutre)

When you run a container (let’s say ubuntu) without any modifications or changes on a Linux host, it shares the same Kernel as the host OS.

From inside the container, we are not be able to see the outside processes (and other resources) because of Linux namespaces.

How about the other way around ? Without any flags or anything, typically, the host can see the processes inside the container because they are all sharing the same Kernel/OS and not inherently considered a security risk from the host’s perspective.

In the below image, notice that the sleep infinity process (PID 576337 in this Host OS) is directly visible on the host. This is the same process we initiated from inside the container, now seen from the host’s perspective

(if the image is too small for you, sorry about that! you can right click on the image and do “Open Image in new Tab”)

If we list all processes inside from within this standard container, as expected, we only see the processes running inside its own isolated environment, starting with PID 1 for /bin/bash.

We can then add --pid=host flag and now we can see everything on the host as well!

I didn’t show the full output because it’s too long but you can trust me that they are the same :D

It is worth highlighting that running containers this way significantly reduces isolation and carries substantial security risks. Never do that unless you fully understand the implications and in trusted environments.

Even if you avoid dangerous flags like --pid=host, the standard containers running on a shared kernel can still face security issues.

A critical example is CVE-2019-5736: A runc container escape

This vulnerability in runc (the default runtime for Docker) allowed a malicious container to break out of its isolation and gain root-level access on the host system.

The big question now is how can we run containers, especially untrusted ones, more safely?

Please enter gVisor.

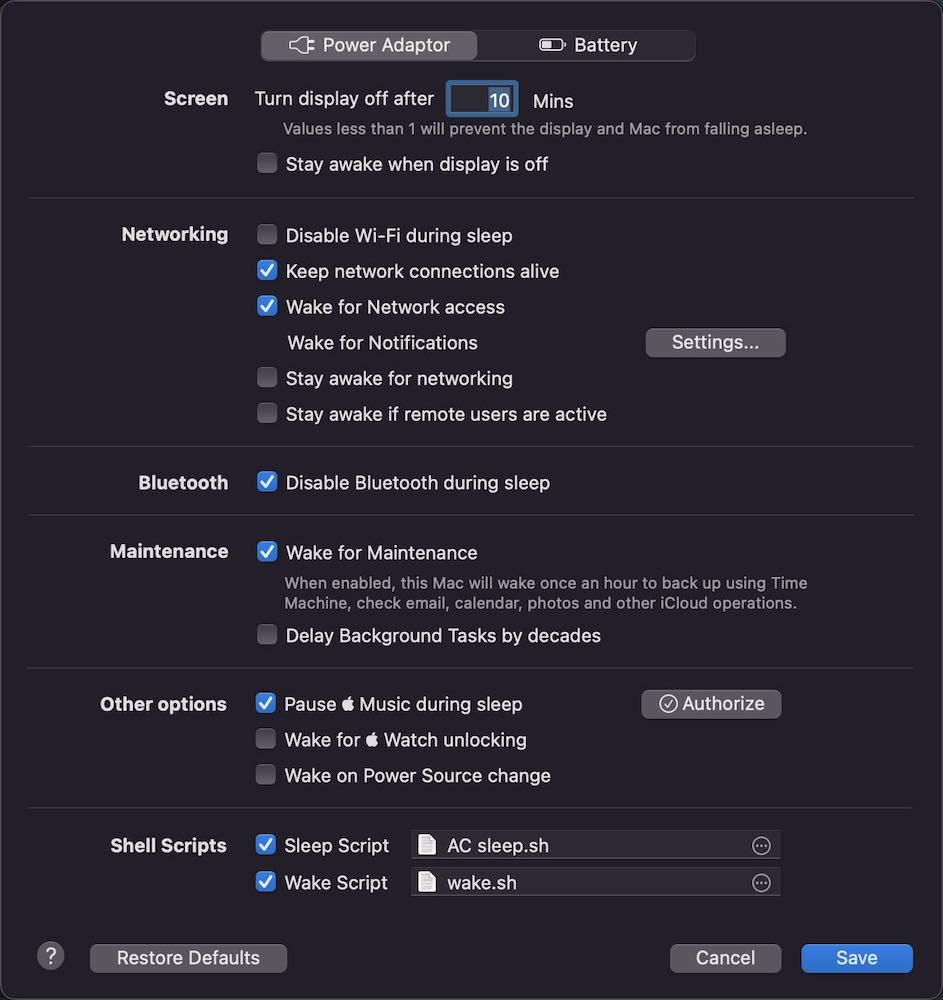

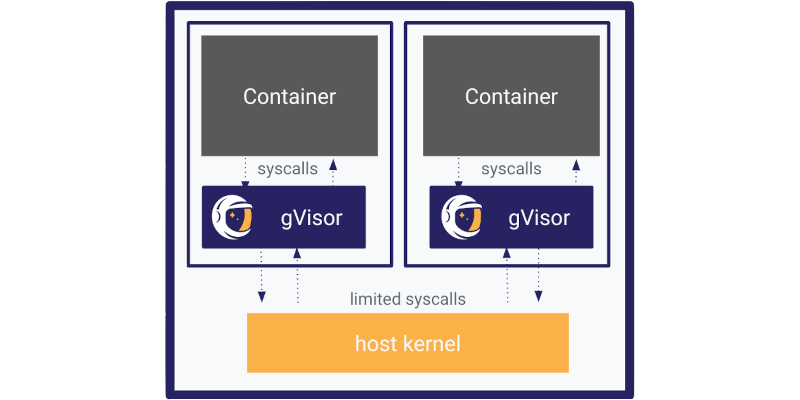

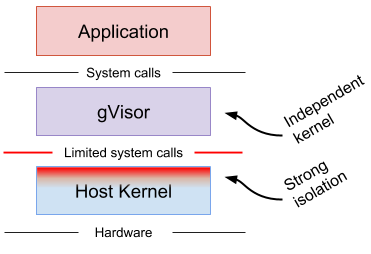

gVisor is an abstraction on top of existing Linux Kernel and acts as a middleman between the container and the Kernel.

It acts as an intermediary, a kind of ‘application kernel’ or ‘user-space kernel’ for the container. This means it emulates the behavior of a normal Linux kernel from the container’s perspective

E.g if I have a program that open() a file and write() to a file, it will be calling gVisor first instead of Linux. That way, the system calls are intercepted and handled by the a gVisor component called “Sentry”, within the gVisor sandbox, not directly by the host Ubuntu kernel.

At this point, you might be thinking, fundamental operations that only the host kernel can do (e.g., actually writing bytes to a network card, or reading from a disk still have to reach to the host kernel, right ?

This is where gVisor gets clever. gVisor is designed to minimize and restrict the types of system calls the Sentry makes to the host kernel. The Sentry operates under a much tighter security policy (using mechanisms like seccomp-bpf) than a typical container. So, it’s not that gVisor never interacts with the host kernel, but it does so in a much more controlled and limited way, significantly reducing the attack surface exposed to the container. This dramatically reduces the attack surface of the host kernel that is directly exposed to the containerized application."

It is safer because of a few reasons

- Reduces the host kernel’s exposure: A vulnerability in a system call implementation within gVisor’s Sentry would, at worst, compromise the gVisor sandbox itself, not necessarily the entire host kernel and other containers. The host kernel is shielded from the majority of the direct system calls from the potentially untrusted application.

- Offers a smaller, more auditable attack surface: The Sentry implements many Linux system calls, but not all of them (there are a lot!), focusing on what typical containerized applications need. Because it’s written in Go (a memory-safe language), it helps avoid many common security pitfalls found in C-based kernels (like buffer overflows, use-after-free, etc.).

- Enforces strong isolation: Even if an attacker breaks out of the application running inside gVisor, they then land in the Sentry. Breaking out of the Sentry to the host system is another, much harder step.

As always, there are trade-offs. The main obvious one is performance overhead. Beacuse it’s intercepting system calls and doing some operations in the userspace, there’s more overhead compared to a direct native system call. e.g apps that do very frequently I/O operations like reading/writing many files will be impacted by this. Other downsides might be debugging. We now have an additional component that I have to check/audit whenever there’s an issue.

Now, let me demonstrate. I have installed gVisor (and its components) on my Linux system. I followed the Docker quick start guide.

We can start a container the same way but with gVisor’s runsc runtime --runtime=runsc flag.

What happens if we do sleep infnity inside the container with gVisor ?

Indeed, the Host OS cannot see sleep infinity directly! This is because the container’s sleep process is managed and contained entirely within gVisor Sentry’s environment.

It is because that sleep process is being managed and contained entirely within the gVisor Sentry’s environment. But we still see it if we do ps aux inside the container itself.

From the Sentry’s perspective, sleep infinity is certainly a process running within its emulated kernel environment (as seen in your container’s ps aux output ). However, crucially, it doesn’t have a directly corresponding distinct Process ID (PID) on the host OS, unlike standard Docker container processes.

The

sleepcommand, especially when asked to sleep for a long duration or indefinitely, will use a clock_nanosleep system call to tell the kernel to pause its execution for a specified amount of time. In this case,infinity

Let’s try another simple command like echo but observe the gVisor logs (located in /tmp/runsc on Host) with some debugging settings enabled.

Every command I run, every file access, every network operation inside the container triggers system calls. When using gVisor, the Sentry intercepts all these system calls. The debug logs clearly show the Sentry actively processing them. The logs are showing that the Sentry processing those syscalls. If you were to strace a process in a standard Docker container, we’d see similar syscalls, but they’d be going directly to your host kernel. With runsc, the Sentry is the first recipient.

I0521 14:33:13.906822 1 strace.go:605] [ 1: 1] sh X read(0x0 host:[1], 0x55ff8db97ac0 "echo \"Hello world\"\n", 0x2000) = 19 (0x13) (11m46.592876238s)

I0521 14:33:13.906902 1 strace.go:567] [ 1: 1] sh E write(0x1 host:[1], 0x55ff8db9a6c0 "Hello world\n", 0xc)

I0521 14:33:13.906917 1 strace.go:605] [ 1: 1] sh X write(0x1 host:[1], ..., 0xc) = 12 (0xc) (5.25µs)

I0521 14:33:13.906933 1 strace.go:567] [ 1: 1] sh E write(0x2 host:[1], 0x55ff8db9a470 "# ", 0x2)

I0521 14:33:13.906942 1 strace.go:605] [ 1: 1] sh X write(0x2 host:[1], ..., 0x2) = 2 (0x2) (2.295µs)

I0521 14:33:13.906964 1 strace.go:567] [ 1: 1] sh E read(0x0 host:[1], 0x55ff8db97ac0, 0x2000)

[ 1: 1] sh X read(...): This shows the Sentry handling areadcall for process ID 1 (which is theshshell) inside its sandbox. TheXprobably means “exit” from the syscall. (strace.go)[ 1: 1] sh E write(...): This shows the Sentry handling thewritecall (to print “Hello world!”) for that same process sh. TheEprobably means “entry” into the syscall (strace.go)- And then repeat the process to print out

#to accept a new command

I hope you get the idea here of what gVisor does and how it roughy works.

How are people using it ?

- List of usecase/users from the official site

- The first generation of GCP CloudRun used

gVisoras noted here but I read that they have moved back to hypervisors/plain Linux Kenel for being more performant for more common workloads. - GKE supports Sandbox, which uses gVisor.

- Fly.io considered using gVisor but opted to go with Firecraker MicroVM instead. Nonetheless, they still have good things to say about it.

So, to receap,

- If you are running a multi-tenant system with containers, especially that allows people to do whatever they want or having something as defense-in-depth, you may wanna consider having gVisor as a layer.

- Always remember the inherent trade-off: balancing the enhanced security gVisor provides against potential performance overhead

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0