The most valuable commodity in the world is friction

Good morning from Orlando, Florida!

This is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

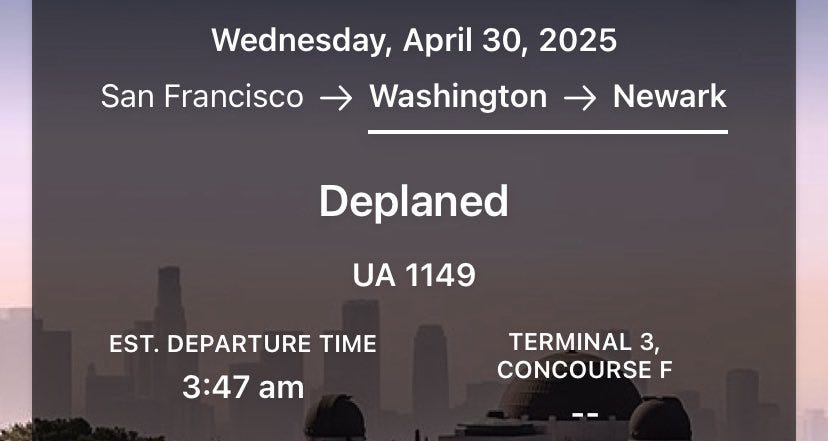

April 30th, 2025. 35,000 feet above the ground. It's 3:17 AM and I'm on a flight from San Francisco circling somewhere above Ohio after being diverted from Cleveland in an attempt to get to NYC. My phone still promises I'll land at Newark on time, albeit 5 hours later than intended, its nice little frictionless interface undisturbed by reality. The pilot's voice crackles over the intercom: "Folks, we're being told the weather's too bad to land. We're heading to DC to refuel." A collective groan ripples through the cabin. The physical world is breaking down again, while the digital tried its best to maintain a comforting illusion.

I want to talk about friction. Not regulations or transaction costs, but the effort required to move through systems, and how that effort is being redistributed in today's economy.

We were taught that effort matters! That working hard, learning well, and building value would be rewarded. I sound a little like old-man-yelling-at-cloud, but I promise I have a point - we have a world where friction gets automated out of experiences, aestheticized in curated lifestyles, and dumped onto underfunded infrastructure and overworked labor. The effort doesn't disappear; it just moves.

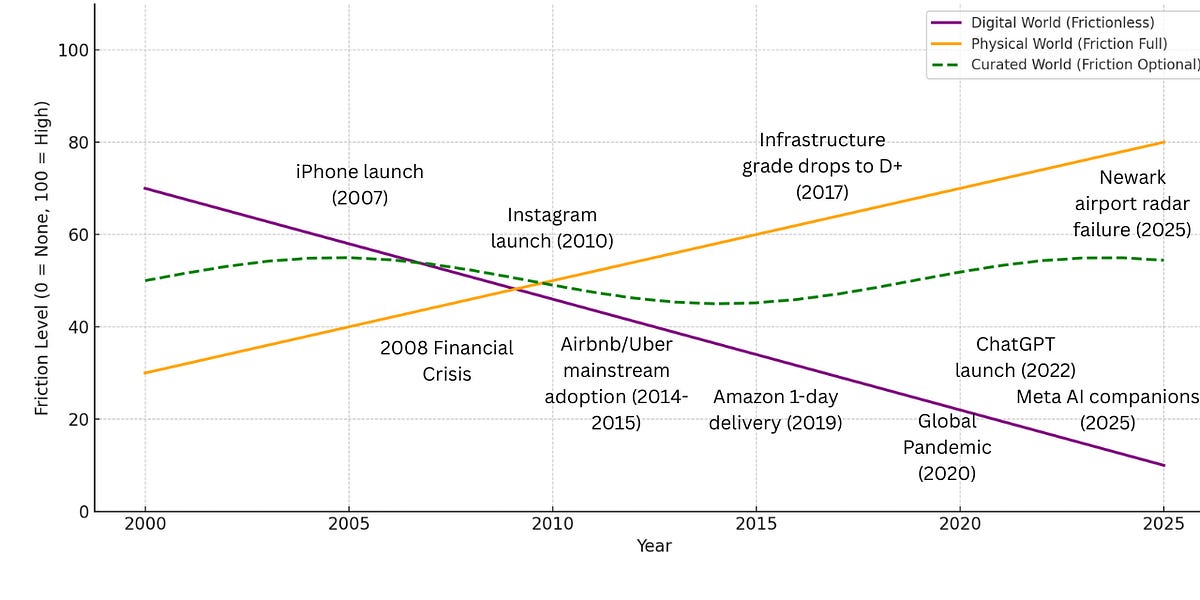

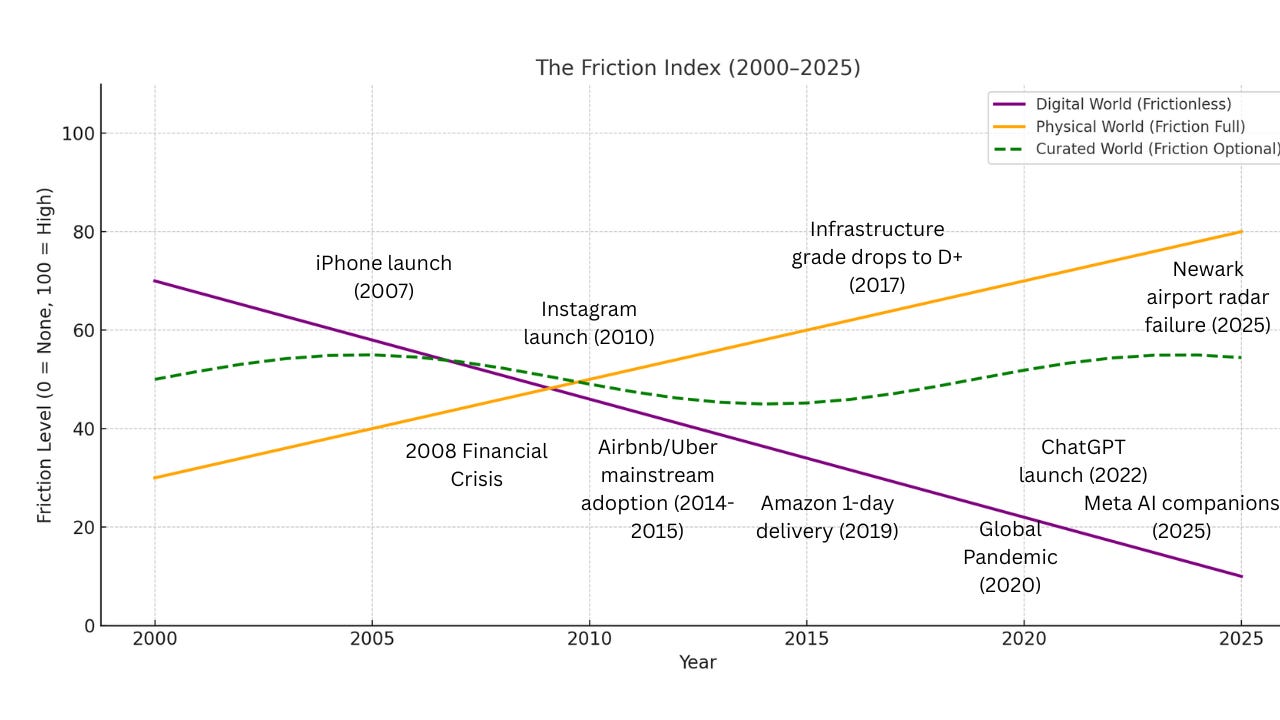

Friction has become a defining feature across the economy, with huge consequences for everything from education to infrastructure. And it's created three distinct worlds that operate by entirely different rules:

The digital world has almost no friction.

The physical world is full of it.

And in certain curated spaces - like the West Village, or your AI companion -friction has been turned into something you can pay to remove.

Here’s what that (very roughly) looks like:

The Digital World

All you have to do is take out your phone to disappear into the frictionless universe of technology. And companies definitely want you to! AI is the newest terrain in a decades-long race to eliminate all forms of cognitive resistance - to build the most complete, most seamless, most profitable mind-melder that follows you across platforms, logs your preferences, and gently nudges you toward products, perspectives, or more recently, policies.

Meta has MetaAI, which lives across WhatsApp, Instagram, and Facebook. It’s not just a chatbot - it’s marketed as a form of social infrastructure. In an interview with Dwarkesh Patel, Mark Zuckerberg (wearing his new Orion glasses) explained why:

The average American has fewer than three friends, fewer than three people they would consider friends. And the average person has demand for meaningfully more. I think it's something like 15 friends or something.

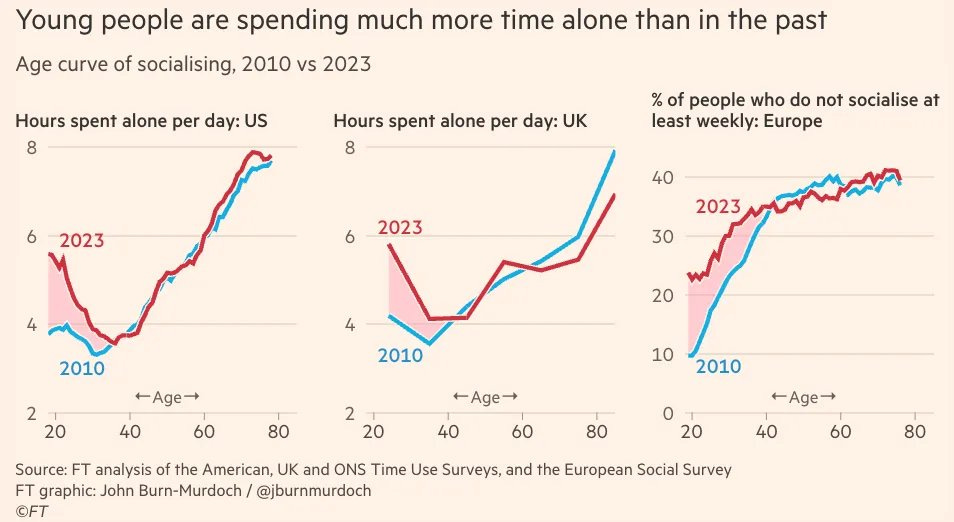

The implication is that Meta will close that friendship gap with AI companions. Zuckerberg clarified they won't replace relationships but "supplement" them, a distinction that reveals the actual business model. We're living through an epidemic of loneliness (as many have discussed), but the solution being engineered isn't more human connection. It's simulated companionship that's both profitable and… frictionless.

The consequences are already here. Meta's AI companions have been caught simulating fantasy sex with underage users (WSJ), Instagram’s AI bots are falsely claiming to be licensed therapists, and and the platform itself is targeting teens who post selfies with beauty ads because, as internal documents put it, “this is what puts money in all our pockets.”

The product strategy is simple: no guardrails. The fewer the limits, the more frictionless the experience, right? And the thing is, Zuckerberg isn't wrong about the demand.

The Metaverse failed (one must imagine he very much wants to be right about AI chatbots), and AI companions might succeed precisely because they remove the friction of real human interaction.

As Samantha Rose Hill wrote, “AI mirrors you. You're being sold back to yourself. It will only increase hyper-individualism and isolation.” And there certainly is already enough isolation, as John Burn Murdoch detailed.

And when all you have to do is buy Trumpcoin to smooth things over maybe nothing really matters.

I think what we're witnessing isn't just an extension of the attention economy but something new - the simulation economy. It's not just about keeping you glued to the screen anymore. It's about convincing you that any sort of real-world effort is unnecessary, that friction itself is obsolete. The simulation doesn't just occupy your attention, right, instead it replaces the very notion that engagement should require effort. Which is… wild.

And people believe it! Of course, they’re building on it. Money is always the lubricant for life, and if people can monetize this, they will. There are startups now, like one called Cluely that promise real-time assistance for everything: campus tests, dating, even thinking. Their slogan is: “So you never have to think alone again.” Their plan is eventually to develop a chip for your brain.

This is what a frictionless world looks like. Everything accelerates, until you forget what it means to try. Apps load faster. Papers write themselves. Job interviews are browser tricks. 60-hour raves, just in your VR Goggles. Speech patterns converge. Aesthetics flatten. Even identity becomes an efficiency layer.

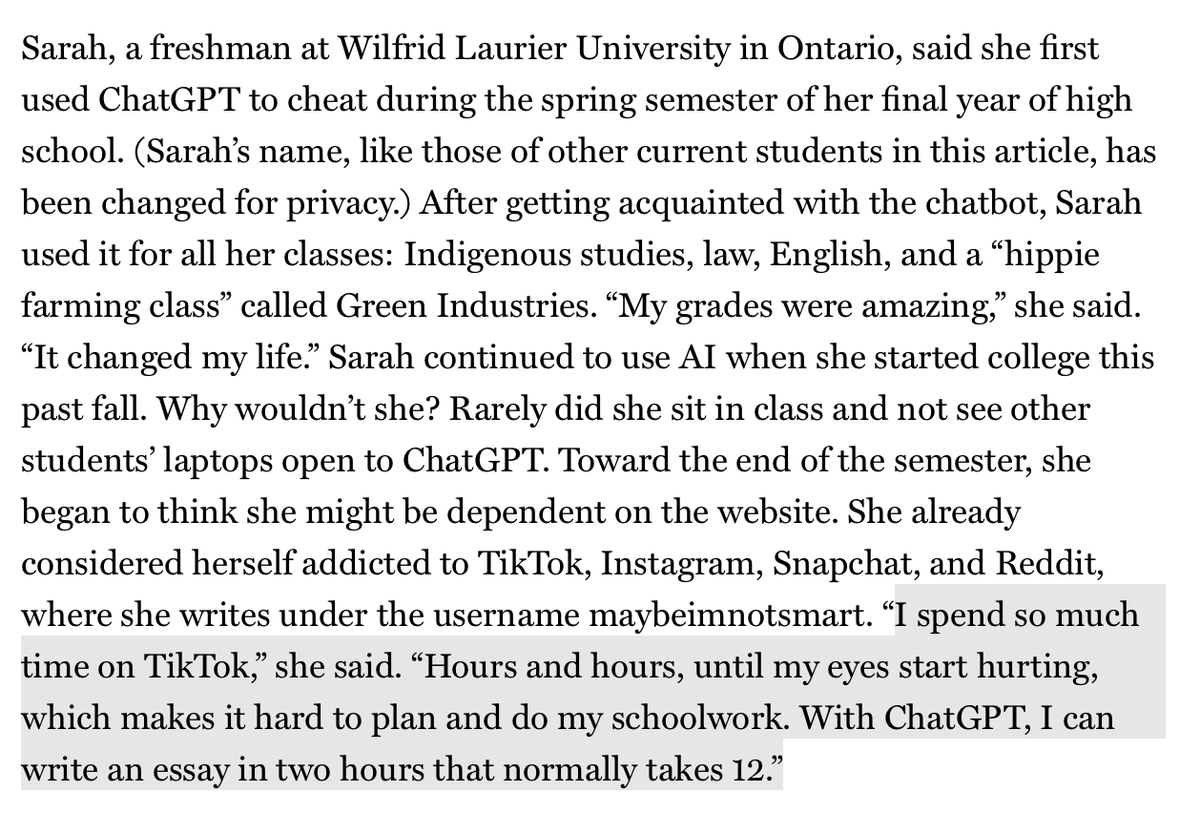

NY Mag has an excellent article on the prevalence of AI in colleges - one student said college now feels like “how well I can use ChatGPT.” Others describe writing essays as a coordination problem: get the prompt, feed it to the bot, skim the output, add some filler, hit submit. No thinking required, just interface management.

‘The Elite College Students Who Can’t Read Books’, an excellent essay by Rose Horowitch talks about this more, and where we went wrong. It’s all about making it through the economy. Learning isn’t learning, it’s a step between you and a job.

Students can still read books, they argue—they’re just choosing not to. Students today are far more concerned about their job prospects than they were in the past. Every year, they tell Howley that, despite enjoying what they learned in Lit Hum, they plan to instead get a degree in something more useful for their career.

Compound that with the ‘socialization collapse’ as Michael Miraflor calls it (the antisocial behavior we see), and we have a real situation on our hands. This is all economically quite weird. The credential still costs money and at least now, still signals value. It still unlocks jobs, internships, visas, and salaries (although the wage premium has eroded over time). But the effort that used to underwrite that value has vanished.

This is a misalignment problem. The economic signal (the diploma) still circulates as if the underlying work has occurred. But the work isn’t there. We’ve just shifted the friction offscreen, and have outsourced it to a chatbot and let the system pretend nothing’s changed. So at this moment, we are credentialing fluency with tools that do the thinking for you.

And yes, cheating has always existed. But this isn’t traditional cheating. It’s ambient, platform-approved, investor-funded cognitive offloading.

And to be abundantly clear, this isn’t the fault of the students - in a winner-takes-all economy, it must be extraordinarily difficult to resist the allure of something like an AI homework machine. But there are questions like: if AI can do the work for you, what exactly are we measuring? What do you do with the free time… scroll TikTok (that answer seems to be yes). And what happens to the labor market when a four-year degree signals nothing about what a person can actually do?

And… how did we get here?

Tanner Greer has a beautiful breakdown of American loneliness, drawing from Tocqueville and Wang Huning. “The American,” he writes, “was an individual first, nothing second.” The result is a culture of deep, systemic isolation. Not just emotional, but economic. Americans work alone, consume alone, get rewarded alone. Even our policies, as Tocqueville feared, are structured around that loneliness.

“When you analyze many government policies [in America] it is not difficult to see that their fundamental motivation [is in fact] the complex and persistent role played by widespread loneliness.”

Loneliness isn’t just personal. It’s institutional. It’s fiscal. It’s a bit engineered. It’s purposeful.

I’ve written a lot about the Trump administration’s economic strategy - and how much of it operates on a kind of kayfabe logic: tariffs as punishment, allies turned into villains, trade reduced to plot points on some grand World Wide Wrestling Entertainment Stage. Everyone is the enemy and no one is a friend - this is a structural form of isolation. A top-down loneliness fiscal policy.

But what happens when the bottom-up version hits back? When digital frictionlessness collides with physical decay? That's where we find ourselves today, straddling worlds that operate by entirely different rules.

The Physical World

Because while the digital world has removed all friction, the physical world is where the friction still lives. Not the good kind, the effort of doing something hard, the kinetic potential of possibility, but the bad kind: the exhaustion of trying to hold together systems that no one’s willing to invest in anymore.

The meltdown at Newark is not a one-off. In fact, it’s probably a leading indicator. As the WSJ reported, when the radar and radio systems failed simultaneously, air traffic controllers were reduced to telling pilots, "We don't have a radar, so I don't know where you are." The failure traced back to a single multiplexer box that was scheduled for replacement hours before the outage but never installed.

This is what happens when we treat public infrastructure like a tech platform… always on, low overhead, minimal headcount. My own diverted flight was just one minor data point in a much larger pattern of problems. The FAA's equipment now fails approximately 700 times weekly. Controllers work 10-hour shifts, six days straight. There's a backlog of replacement parts for components nobody manufactures anymore.

When systems that were designed for resilience are optimized instead for efficiency, they break. And what's most telling isn't the technical failure itself, but the official response from the FAA: slow things down. If radar fails, hold the planes. If communications drop, delay departures. It's a stopgap strategy that acknowledges deterioration as the new normal.

What's interesting is how our digital systems actually depend on this decaying physical infrastructure, yet provide no visibility into it. Elements of the same airport radar system that failed in Newark powers the operation of travel booking apps and flight trackers. When the physical backbone collapses, the digital outlet layers instantly evaporates, revealing how thin that tiny veneer of frictionlessness really is. It's a system held together by exhaustion and analog wiring. As one air traffic controller said:

“The situation is, has been and continues to be unsafe, and it is only a matter of time until a lot of people die… The equipment is unsafe to use, and unusable—both [communications] and radar. The amount of stress we are under is insurmountable.”

We’ve stopped expecting the real world to work. We assume it will be slow, broken, or possibly on fire. That’s just the baseline. But between the frictionless digital world and the friction-saturated physical one lies a third space - a buffer zone between the real and the simulated.

The Curated Real World

So the digital world has removed friction and the physical world is drowning in it - but there’s the third space. The curated world. Spencer Kornhaber wrote about the… blandness of new art in the Atlantic, stating:

So-called zombie formalism—rehashed abstract expressionism optimized for Instagram shareability—became a fad. Minimalism, a presumed antidote to the chaos of online life, became the default aesthetic in art, fashion, and consumer-product design.

He continues:

[Dean Kissick] wants art to address the internet’s more ineffable consequences: rendering our thought processes glitchy, destabilizing our sense of self… “The culture we have is so obsessed with ourselves, with people’s identities and personalities,” he said. “Perhaps we’ll be able to transcend that somehow. Perhaps we will get over this deeply individualistic, deeply self-obsessed moment.”

The West Village Girl is probably the best example of this sort of zombie formalism, deeply self-obsessed moment. West Village is an NYC neighborhood that serves as a production set for an optimized lifestyle. You can live your entire life within a five-block radius: Pilates, three-drinker dinners, charm bars, espresso martinis, run clubs, spritzes, connection. It’s great.

Life, in a sense, is not about reducing friction, it’s about styling it and that’s the value proposition here. A structured sense of belonging that happens to look incredible on Instagram. Everything is close. Everything is cute. Everything is camera-ready. It is so extraordinarily logical in the current economy!

This isn’t unique to West Village. There are all sorts of spots that do this strange, careful curation of friction. The boutiques are selling the appearance of effort without its substance. Hand-crafted aesthetics at mass-production prices. Rustic cafés with lighting fast WiFi. This illusion of locality with the convenience of globalization (pre-tariffs, at least).

None of this is a critique. It’s a function. These neighborhoods are running a different kind of system - one where you can still feel like the world works, because someone else is dealing with the parts that don’t.

This is the economic story: friction has become a class experience. Wealth has always helped smooth over bumps - but when the physical world is such a mess and the digital world is so easy, it’s simple to curate the digital into the physical if you have money.

Like… for many, college isn’t where you go to learn. It’s where you go to network. I was taking an Uber to JFK last week (no Newark for me on the way home) and my Uber driver was trying to break into finance. So for an hour and a half, we talked about his path. He had moved from Nigeria with a Masters in International Marketing, and used his time between drives to study for the SIE. Someone who worked at one of the big banks told him - “Don’t bother studying, it’s all about who you know. You need to know people to break into this world”.

Roy Lee said the quiet part out loud in that NY Mag piece: “It’s the best place to meet your co-founder and your wife.” (I guess everyone wants an MRS degree in the end). He went to Columbia for adjacency. The institutions still look like they’re doing what they used to do. But now, they’re set pieces for a different kind of outcome.

It’s the same logic that powers Erewhon, or Soho House, or influencer-run startups. You’re not paying for the thing. You’re paying for the removal of difficulty. The filtered lighting. The social cachet. The sense that this world still makes sense!

The Long View: Buffett's Exit at the End of an Era

Earlier this week, Warren Buffett announced he's stepping down after sixty years as CEO of Berkshire Hathaway.

Buffett, who rode the greatest economic expansion in human history, is departing just as the friction of that system becomes impossible to ignore (and he is 94 years old). He is amazing. And he had some lessons:

We still have very substantial inflation in the United States, but it's never been runaway...yet […] And that's not something we want to try and experiment with, because it feeds on itself.

He sees the unsustainability of our current economic model with clear eyes:

With roughly a 7% gap [in the budget deficit], when probably a 3% gap is sustainable. And the further away you get from that, the more you get to where the uncontrollable begins...

Buffett's comments hint at the price of frictionlessness. The American economy has been running a decades-long experiment in removing friction, both through technological advancement and through financial engineering that pushes costs into the future. The resulting prosperity has been very real, but it's been built on the proverbial kicking the can down the road. His reflection on the healthcare system is important too:

There are problems as a society when you get 20% of your GDP going into a given industry... We came to the conclusion: we didn't know the answer... We had the money to do it, and we didn't know how to change how 330 million people felt about their doctor, felt about their healthcare, what they felt entitled to. It won't change by itself. And the government is the only one that can change it.

This is the friction economy in microcosm. A system that everyone knows is inefficient and unsustainable, but persists because the friction of changing it despite many, many people trying - the actual work of building consensus and implementing new structures seems insurmountable.

Buffett himself recognizes the need for massive reinvestment:

It's obvious that the country needs major reinvestment and rethinking—especially in critical infrastructure. America has outgrown parts of its current model.... But it's clear: the need is urgent and the investment required will be hundreds of billions of dollars. Too many people are focused on assembling funds and charging fees—not actually deploying capital efficiently or effectively. That's not a long-term solution.

He's describing precisely the physical world of accumulated friction. The multiplexer box at Newark was the entirely predictable result of a system optimized for short-term gains rather than long-term resilience.

The Friction Economy

What's important about these three worlds - digital, physical, and curated - isn't just that they exist in parallel but that they actively feed off each other. They operate like a closed economic system, where friction isn't eliminated so much as transferred from one domain to another.

When Mark Zuckerberg's Meta builds frictionless social interfaces, that cognitive smoothness is subsidized by somewhere, somehow, right? The same economy that produces simulated friends for the lonely American also produces understaffed air traffic control towers. The same investor class that funds "never think alone" startups also lobbies against infrastructure spending, or perhaps, housing.

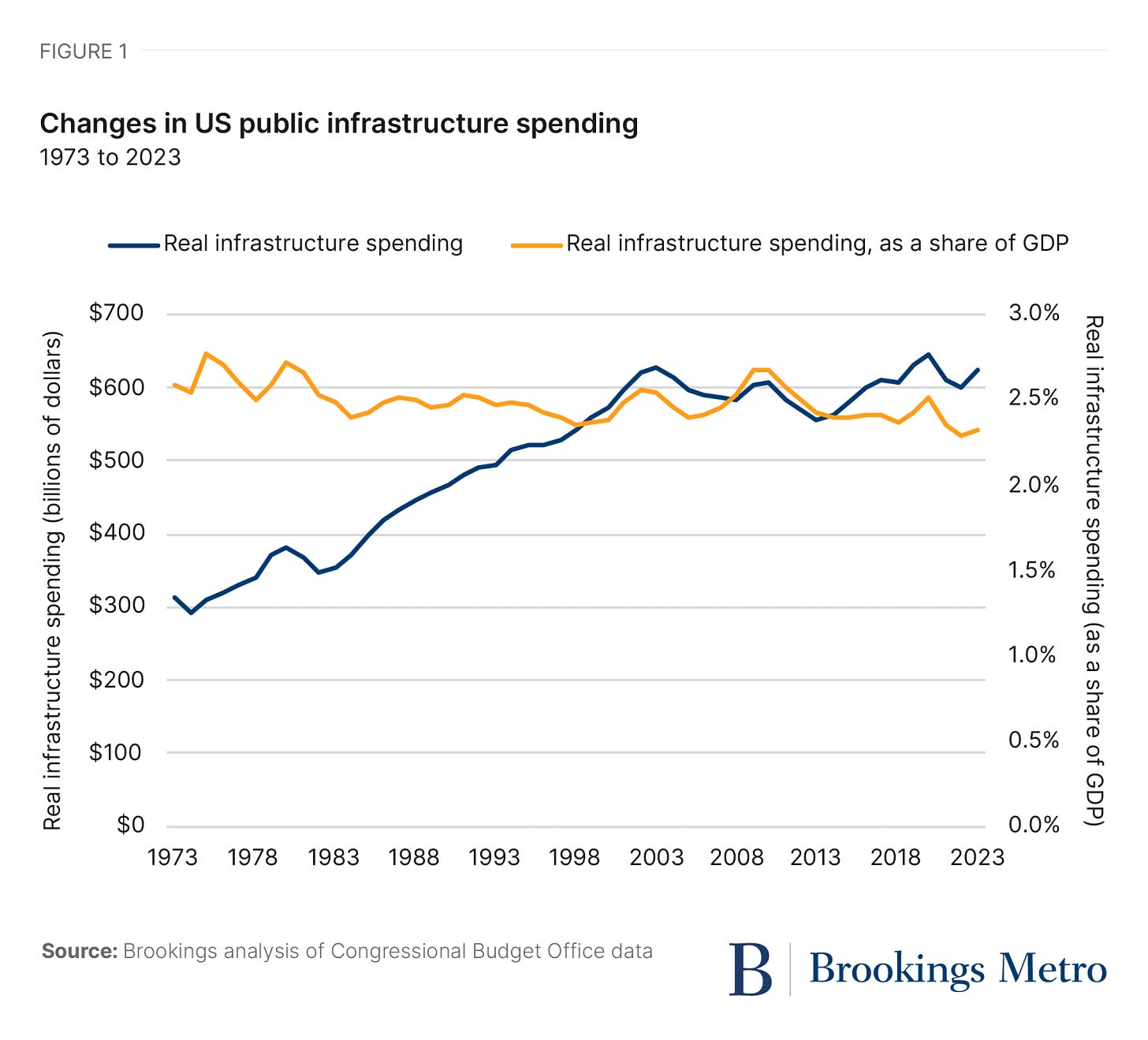

This is structural. A recent analysis from the Brookings Institute that public infrastructure spending as a percentage of GDP has fallen to its lowest level over the last two decades. Tech megacaps plan to spend more than $300 billion in 2025 in the AI race. Different money, different places, different things, but the same economy that generates unprecedented digital wealth struggles to maintain bridges, water systems, and yes, air traffic control equipment.

The digital world does extract value from the physical:

Amazon's one-click ordering creates a seamless customer experience by offloading friction onto warehouse workers and delivery drivers.

ChatGPT generates essays without effort, but that seeming magic requires data centers that strain local infrastructure.

When students use AI to write papers, the friction doesn't vanish, it accumulates as future knowledge deficits.

When Newark's radar systems fail, the friction materializes from years of deferred maintenance and disinvestment.

The system always balances its books eventually. The more we optimize individual experiences for frictionlessness, the more collectively dysfunctional our systems become. All three worlds are interlocked in this economy of friction

In the digital world, effort is irrelevant. The chatbot does the thinking. The essay writes itself. You can vibe your way to a degree with a 20% sprinkle of “humanity,” and the credential still prints.

In the physical world, effort is everywhere. Air traffic controllers are running on trauma leave. The radar fails. The copper wire breaks. And the solution is not to invest, it’s to slow everything down.

In the curated world, effort is stylized and it’s optimized and it’s curated. The people who live there aren’t lazy or disconnected, they’ve just found a way to route around collapse. Life still works, but only in zones that are small enough to manage and expensive enough to protect.

This is the economy now. Not a distribution of opportunity. A redistribution of friction. But friction isn’t the enemy!!!! It’s information. It tells us where things are straining and where care is needed and where attention should go.

And it's not all bad news. Because friction is also where new systems can emerge. Every broken interface, every overloaded professor, every delayed flight is pointing to something that could be rebuilt with actual intention.

We are seeing this happen in pockets. Take a look at what Mississippi has accomplished with education - it has the fastest improving school system in the entire country. These are minor currents against the major flow of capital and attention.

But they suggest an alternative to both digital frictionlessness and physical collapse - a world where effort is neither eliminated nor wasted, but directed toward systems that actually sustain us. Maybe it’s things like requiring tech platforms to internalize costs they currently externalize to physical systems and human attention (challenging) or educational models that reward deep engagement rather than interface management (also challenging). But we have to acknowledge that when we remove friction from one domain, we're not eliminating it, we're just moving it somewhere new.

In the meantime, I told my Uber driver that he should continue to study but do outreach to firms because unfortunately, that guy who works at the big bank is correct. The systems may be changing, but the power structures remain stubbornly intact. And understanding how friction flows through them - who gets to avoid it and who gets crushed by it - tells us everything about how our economy actually works.

This is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Thanks for reading. Also - the Fed held rates. No one knows what is going to happen next - but some element of friction will probably be involved.

Inspired to get this out by Birb’s tweet but I have been working on a very long-form (ahem, perhaps a book outline) on this topic for a few months now

Really excellent piece by Bloomberg analyzing who exactly is buying Trumpcoin… and why

Kate Wagner’s AI and Internet Hygiene piece eternally important here

Jeremiah Johnson has a really interesting piece in The Dispatch this week around the antisocial behavior we’ve been seeing in some pockets and what that has created

I do think Adam Tooze is right - the sheer force of the Administration, the bold demands, the direct challenging that we see - a lot of it sucks, but a lot of it had to happen.

And there are elements of socialism, as Kevin Williamson writes about

It’s getting worse too - Secretary Bessent was supposed to meet with China to talk trade, but the day after that was announced Trump tweeted out “No potential to pulling back tariffs on China”. China is now telling the EU to join them in fighting the US. Not great.

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0

![Africa CEO Forum : énergie, IA, routes… les paris du continent [Business Africa]](http://static.euronews.com/articles/stories/09/27/46/96/640x360_cmsv2_01295edd-3441-5908-8c4e-adb7e75b9f71-9274696.jpg?1746786054#)