NHS rejects use of two breakthrough Alzheimer's drugs because of cost

Breakthrough Alzheimer's drugs too pricey for NHS

James GallagherHealth and science correspondent•@JamesTGallagher

Getty Images

Getty ImagesTwo breakthrough Alzheimer's drugs have been deemed far too expensive, for too little benefit, to be offered on the NHS.

The medicines are the first to slow the disease, which may give people extra time living independently.

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) concluded they were a poor use of taxpayers' money and said funding them could lead to other services being cut.

Campaigners say it is a disappointment, but dementia experts have also supported the decision.

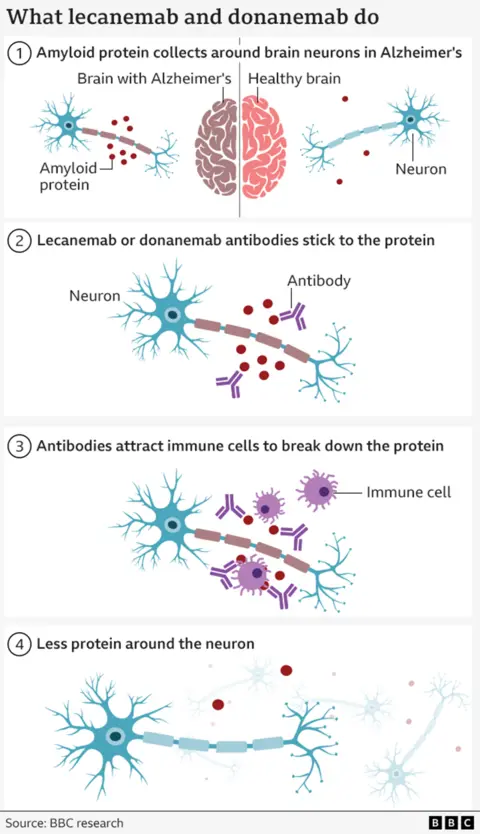

The two drugs, donanemab and lecanemab, both help the body clear a gungy protein that builds up in the brains of people with Alzheimer's disease.

The medicines do not reverse or even stop the disease, rather brain power is lost more slowly with treatment.

Clinical trials of these drugs were celebrated as a scientific triumph as they showed, for the first time, it was possible to change the course of Alzheimer's.

But since then a row has developed over the cost of the drugs and how meaningful the benefit is.

The official price in the US is £20,000-£25,000 per patient per year. What the NHS would pay is confidential.

Around 70,000 people in England with mild dementia would have been eligible, potentially putting the bill in the region of £1.5bn a year for the drugs alone.

NHS resources, including regularly infusing the drugs directly into spinal fluid and frequent brain scans to manage dangerous side effects, would also massively ramp up the cost.

Will the NHS ever pay for the new era of dementia drugs?

The benefit of the drugs is also debated. They potentially delay the transition from mild to moderate dementia by four-to-six months. That could mean more time without needing daily care, driving, being present for significant family events and socialising.

But Prof Rob Howard, from University College London, said real-world benefits "were too small to be noticeable". In trials of lecanemab, patients were better off by 0.45 points, on an 18-point scale ranging from healthy to severe dementia.

Yet he said the cost would "have been close to the cost of a nurse's salary for each treated patient".

The decision not to fund the drugs is not a surprise. The first assessment last year concluded they were not cost-effective.

Helen Knight, director of medicines evaluation at NICE, acknowledged the latest news would be "disappointing" but said the benefits were "modest" at best while requiring "substantial resources".

"If they were approved they could displace other essential treatments and services that deliver significant benefits to patients," she said.

NICE said its appraisal had factored in potential savings in the cost of providing care, but the drugs were still deemed unaffordable.

NICE decisions apply to the NHS in England, but are normally adopted by Wales and Northern Ireland too. Scotland has its own method for approving drugs.

The pharmaceutical companies have three weeks to raise concerns about how the review was performed, otherwise the decision becomes final on 23 July.

Both pharmaceutical companies involved, Eisai for lecanemab and Eli Lilly for donanemab, say they will appeal against the decision.

Nick Burgin, from Eisai said the NHS "is not ready" for the challenge of tackling Alzheimer's and flaws in the process meant their drug would have been rejected "even if Eisai provided lecanemab to the NHS for free".

Eli Lilly, the company behind donanemab, has already expressed its disappointment.

"If the system can't deliver scientific firsts to NHS patients, it is broken," said Chris Stokes, Eli Lilly's president and general manager of UK and Northern Europe.

Is this a distraction or a disappointment?

The sentiment was echoed by both the Alzheimer's charities. Prof Fiona Carragher, from the Alzheimer's Society said "the science is flying but the system is failing" and it was "highly disappointing" the drugs were not available on the NHS.

Hilary Evans-Newton, the chief executive at Alzheimer's Research UK, said the result was "painful" and patients will miss out on this and future innovations "not because science is failing, but because the system is".

However, others say NICE has made the right call. Tom Dening, professor of dementia research at the University of Nottingham, said he was "in complete support" as the benefits of the drugs were "minimal" and a "distraction" from the real issues in dementia.

"[Namely the] unglamorous challenge of providing people with dementia and their families with activities, care and support that we already know are beneficial for their mental and physical health," he said.

Prof Atticus Hainsworth, from St George's, University of London, said: "NICE is simply doing its job."

Beyond lecanemab and donenamab there are 138 dementia medicines being tested in 182 trials around the world.

Prof Tara Spires-Jones, director of the centre for discovery brain sciences at the University of Edinburgh, said: "There is hope for safer, more effective treatments on the horizon."

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0