Flounder Mode – Kevin Kelly on a different way to do great work

Kevin Kelly isn’t known for one ‘big thing’, and doesn’t aspire to be. He’s as intelligent, hard-working, ambitious, and prescient as history’s most iconic entrepreneurs—only without any interest in building a unicorn himself. Instead, in his words, he works “Hollywood style”—in a series of creative projects. What follows is a sampling of his life’s work.

Kelly was an editor for the Whole Earth Catalog in the early 1980s, helped start WELL, one of the first online communities, in 1985, and co-founded WIRED magazine in 1993. He’s written a dozen books and published hundreds of essays on topics from art to optimism, travel, religion, creativity, and AI (even before it was a thing). Kelly rode a bicycle across the United States in his 20s. He was Steven Spielberg’s ‘futurist advisor’ on Minority Report, and the inspiration behind the famous ‘Death Clock’ on Futurama, after the show’s creator Matt Groening caught wind of the Life Countdown Clock Kelly keeps on his computer desktop. He organizes tightly curated group walks across Asia and Europe, regularly covering ~100km in a week. He sculpts, draws, paints, and photographs. And he’s a longtime friend and collaborator of Stewart Brand (whose famous line, “Stay hungry, stay foolish,” Steve Jobs quoted in his iconic commencement address at Stanford).

To encourage long-term thinking, Kelly is helping build a clock into a mountain in western Texas that will tick for 10,000 years. Brian Eno and Jeff Bezos are active collaborators. He’s a born-again Christian. He’s been married to his wife, Gia-Miin, for 38 years, and they have three children together. He was pivotal to a fringe-turned-mainstream movement to identify and catalog every living species on earth (now owned and operated by Smithsonian). He was early to think and write about the quantified self, which gave rise to products like Fitbit, Strava, Apple Watch, Eight Sleep, and the Oura Ring. Kelly’s idea of “1,000 true fans” practically christened the creator economy with his 2008 insight that “if 1,000 people will pay you $100 per year, you can gross $100k—more than enough to live on for most.”

The people who become legendary in their interests never feel they have arrived. Kevin Kelly

Naval Ravikant has called him a “modern-day Socrates,” Marc Andreessen has said that “everything Kevin Kelly writes is worth reading,” Eno called him “one of the most consistently provocative thinkers about technology and culture,” and Ray Kurzweil said that “Kevin Kelly understands the direction of technology better than almost anyone I know.”

Kelly’s Hollywood style of working has always resonated with me; it’s the way I aspire to work and largely have since starting my career. Yet now, 15 years in, I’ve become self-conscious about it. Working in Silicon Valley will convince you that starting a company with its sights on unicorn status is the only possible way to make an impact, and the only work worthy of an ambitious individual.

Kelly is a cheerful and enterprising repudiation of that path, and I didn’t get very long into my interview preparations to realize that I wasn’t only writing about a personal hero; I was seeking a way to make peace with my own professional choices. After a day together, I realized that my pilgrimage to meet the man in his element might also grant permission to others in our line of work who are interested in charting a different course to impact.

I started my career at Google selling AdWords to small businesses, and finished my first quarter as the number three seller in North America. Professional opportunities immediately unfolded—early nods for management, trips to global offices to present my “best practices,” my face on slides next to impressive metrics, and attention from more senior leaders.

It’s hard to say why none of that seemed very interesting, but it didn’t. What I did like was starting a campaign to rename the conference rooms and helping my coworker launch his internal content series, G-Chat with Charleton, in which he would interview Google executives while sitting with them in a two-person snuggie. I had earned myself a ticket to the fast career track at one of the coolest companies in Silicon Valley, but climbing the corporate ladder just wasn’t for me.

So I spent the next 10 years chasing what seemed most fun. After 14 months at Google, my work bestie, Jenny, and I left Google together to give the startup thing a try. We went to a mobile gaming company where I learned to make my way around spreadsheets, play Magic: The Gathering, and cash in on a blockbuster ‘pet hotel’ game. Eighteen months later, it was a six-person startup that was known as “the black sheep of Y Combinator.” In my free time, I coached a JV high school soccer team, volunteered at Dandelion Chocolate (all that working on software made me want to make something with my hands), and finished writing a novel.

My resume of under-two-year gigs spooked recruiters, except for one at Stripe. “We’re impressed by how much ground you’ve covered,” was the backhanded compliment I got. I started on the Account Management team in early 2015.

I spent nearly five years at Stripe, but the lily-padding continued—only this time it was all under one roof. A year into my tenure, I was given the choice between management or a nebulous role focusing on projects that would impact company culture. Like evolving our tradition of work anniversary celebrations, standing up company planning, establishing Stripe as a carbon-neutral company, getting non-developers to participate in our annual hackathon, defining our version of the ‘bar raiser’ interview, and printing and distributing a book (which eventually became Stripe Press). With very little pressing, I learned this nebulous role had emerged from the growing pile of projects that the former McKinsey consultants on the Business Operations team were avoiding.

Guess which role my friends and parents thought I should choose? Guess which one I chose.

Kelly would say it’s good to have an ‘illegible’ career path—it means you’re onto interesting stuff.

I started to take pride in this ‘cool girl’ approach to work. I joked about having never been promoted, but could feel my scope, impact, and relationships with colleagues growing. I remember rejecting a (well-meaning) manager’s suggestion to build out a five-year career plan. I scoffed at people who cared about titles, did things for money, and had professional headshots on their LinkedIn. I mocked MBAs, bragged about “staying off the org chart,” and being good at “giving away my LEGOs.” I became the person you asked to have a coffee with when you wanted to quit your job and do something weird. Once I mentioned “enjoying working in the wings,” and a (well-meaning) executive suggested I “keep that to myself if I wanted to be seen as a leader.” I ignored the advice.

And then, I’m not sure when the switch flipped, but I started to have a sinking feeling that I had it all wrong the whole time. I looked around and felt I was being outpaced by my colleagues—specifically by the MBAs and the people who chased titles, promotions, money, and building teams. And it wasn’t just a vanity thing. They genuinely seemed to be focused on bigger, more interesting problems. And they were having more impact. They were mentoring young talent, influencing top lines and bottom lines, and had their fingerprints on all kinds of cool industry-recognized work. They seemed to always have invitations to exclusive gatherings and job offers in their inbox. Several started companies, and rumor had it that some had term sheets before investors even opened their decks. I didn’t only feel jealous of their work; I felt unqualified to do it. That stung.

I started to reflect on my own trajectory with fear that it didn’t mirror my ambition, work ethic, or deep care about the role of work in a life. Had I pointed my ambition in the wrong direction? What did I have to show for all my effort? Had I made some irreversible, unforced error with my career? How much money had I left on the table? Would the people I respected respect me back for much longer? Despite working my butt off for a decade, I had no expertise and no line of sight into where I was going. I felt immature for placing such a high value on “fun” and “bouncing around,” and full of regret about not picking a lane (or even better, a ladder). It had become hard to explain what I was good at—most importantly to myself. My sister had recently made partner at a prestigious law firm, and it seemed easier for my parents to be proud of her than of me. I couldn’t really blame them.

Kevin Kelly would say it’s good to have an “illegible” career path—it means you’re onto interesting stuff. But I wasn’t so sure anymore.

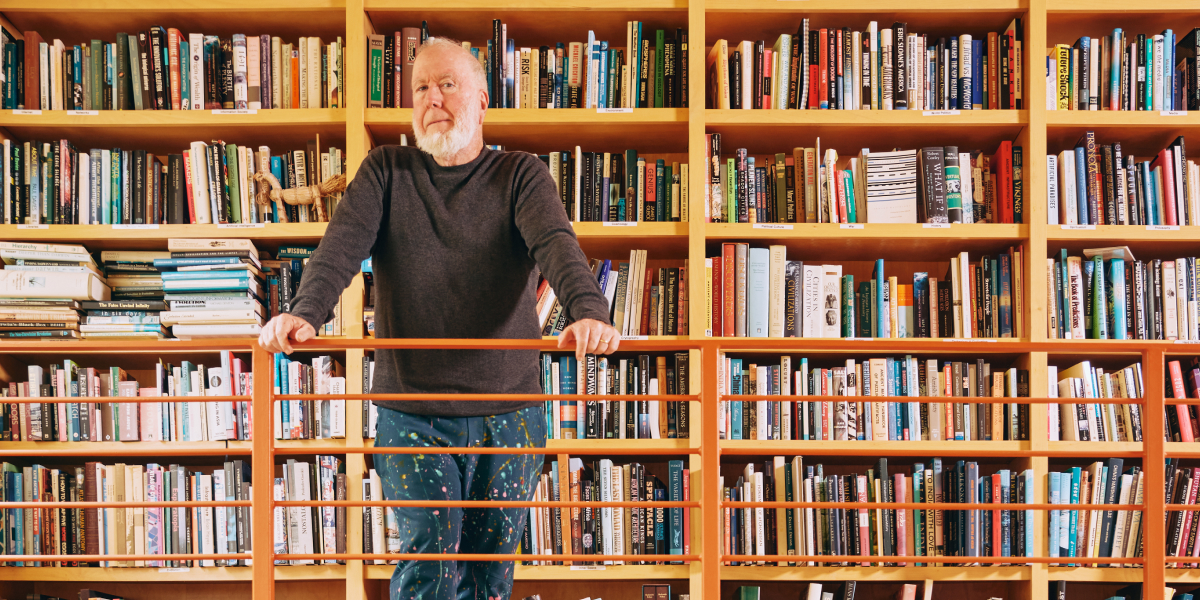

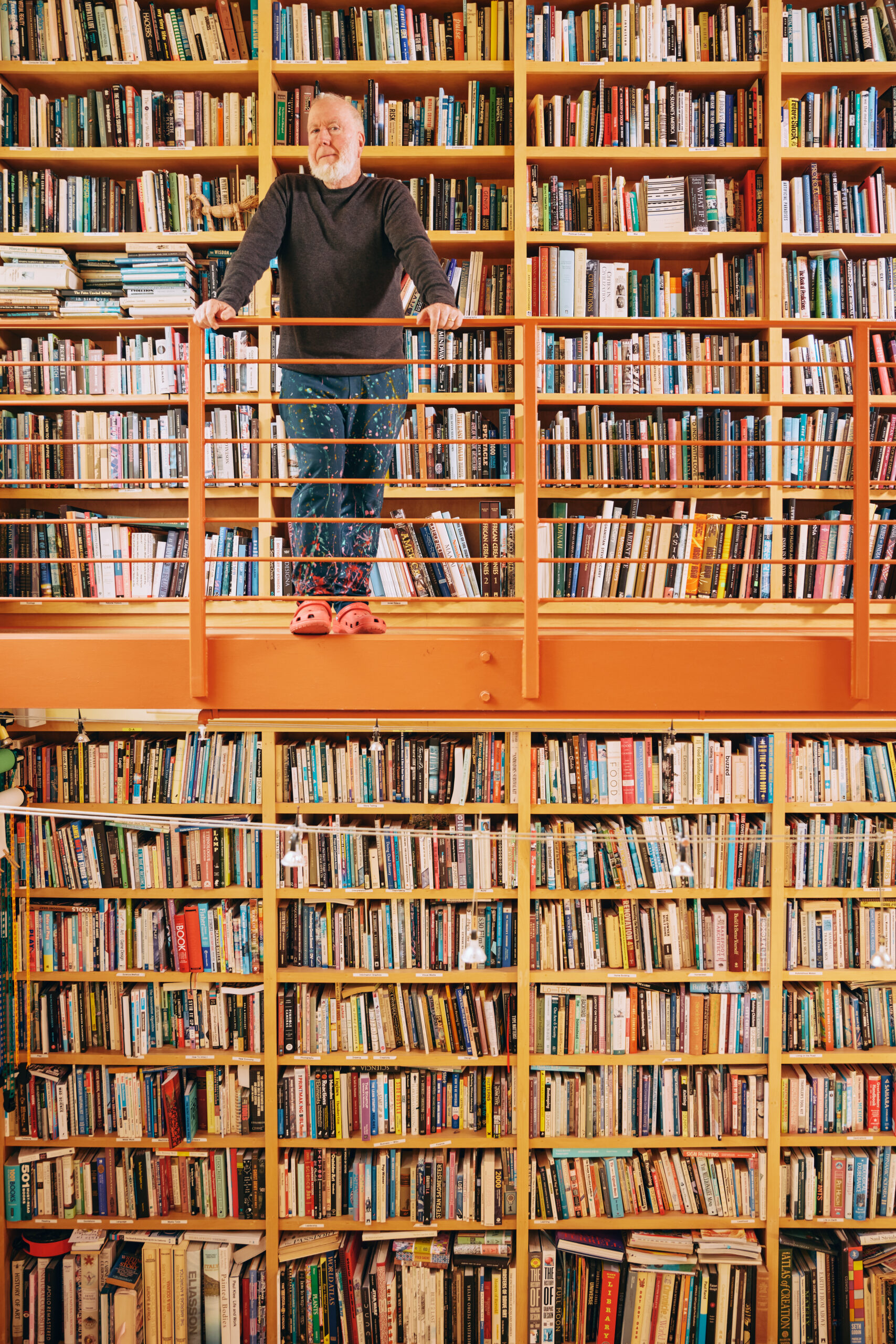

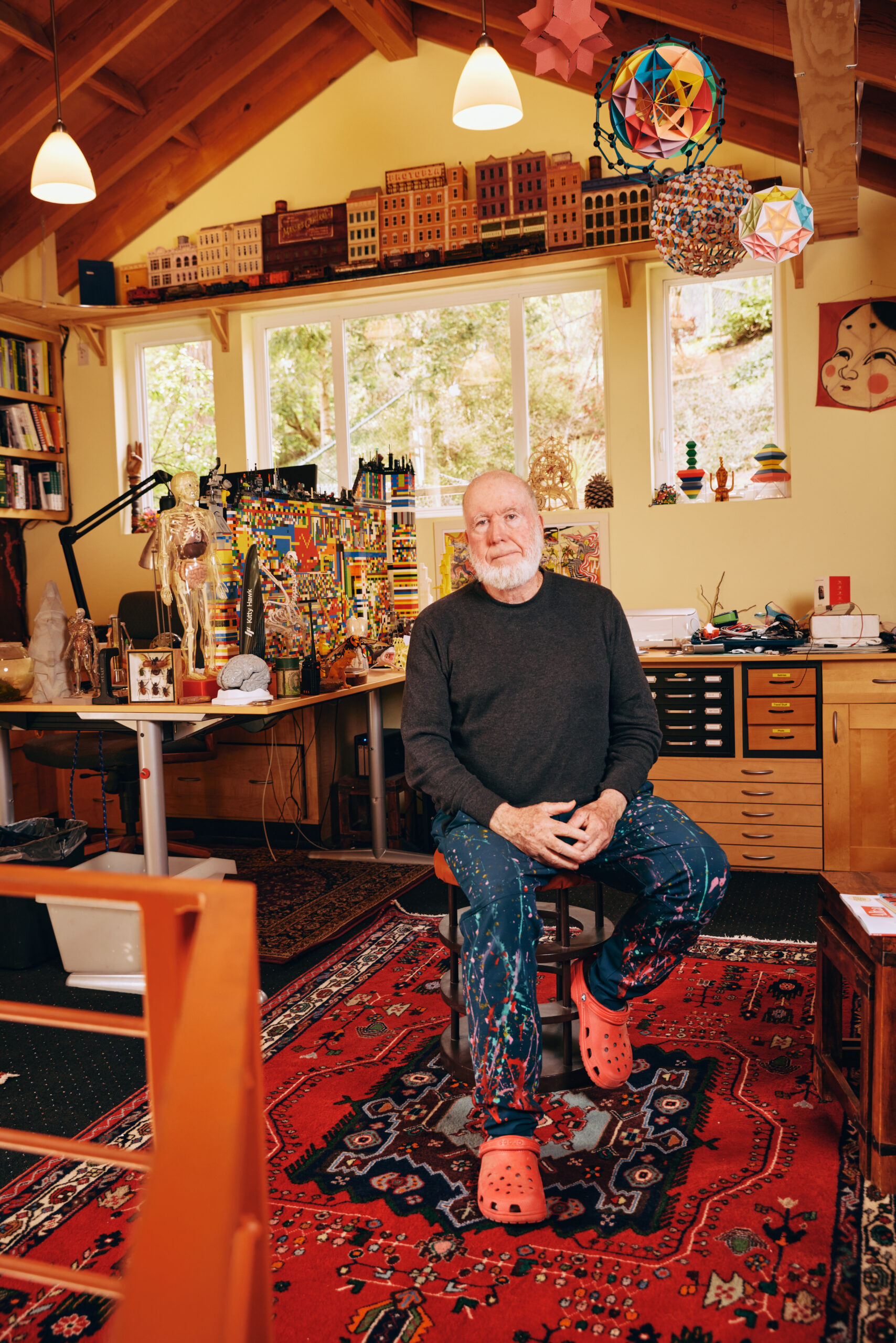

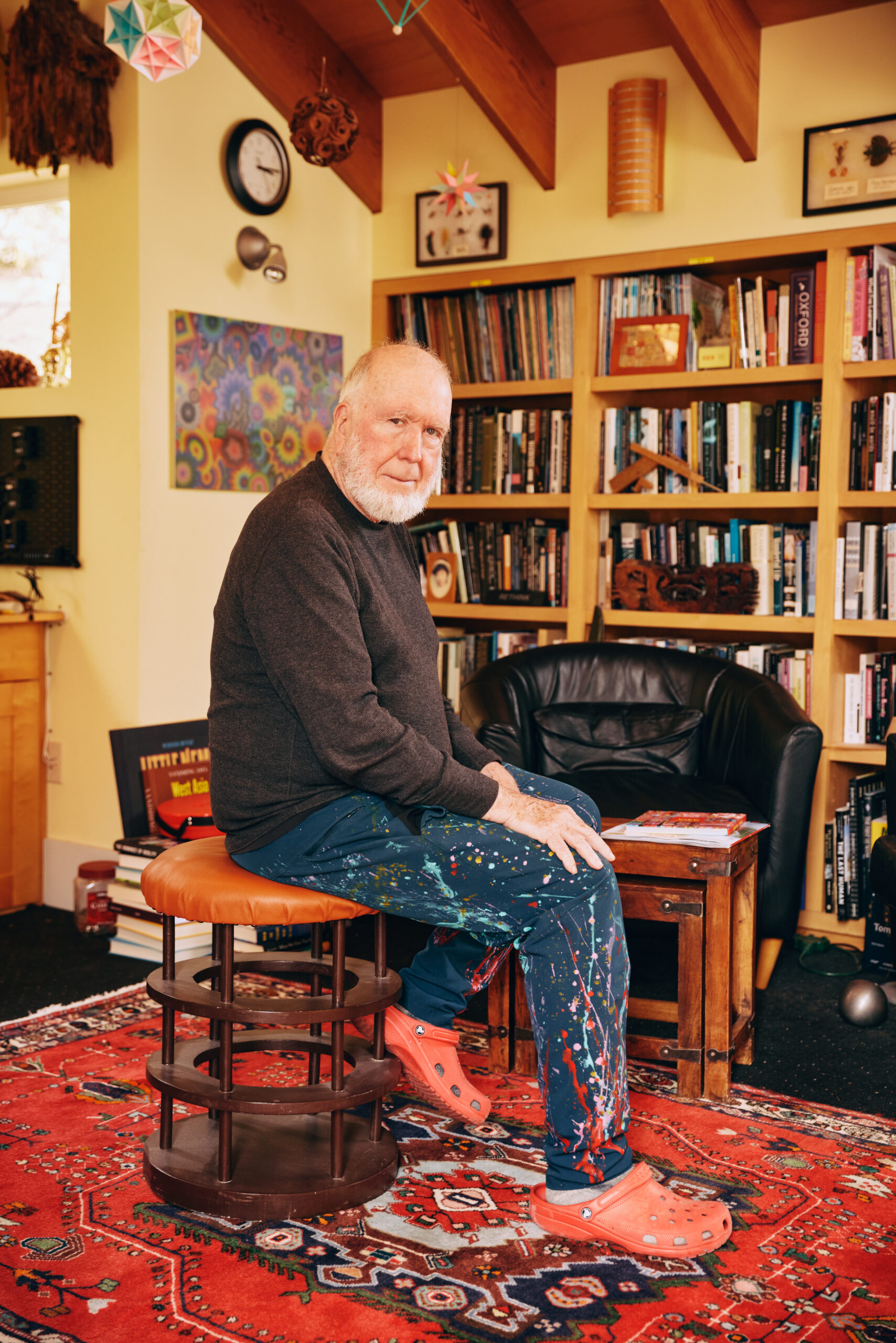

I pull up to Kelly’s Pacifica, California studio—the last house at the very edge of Vallemar off Route 1. It’s a big, barn-looking structure pressed up against a steep hill, which is covered in wild flowers and towering trees. It was overcast and smelled like the ocean and eucalyptus. The only way I knew I’d come to the right place was the very small sign on the door that read ‘kk.org’, on which I’ve spent dozens of hours over the years.

Stepping inside, I felt like I’d time-traveled back to the early 1990s and entered my little brother’s dream bedroom. There were huge LEGO towers, K’nex sculptures hanging from the ceiling, and a massive wall of books spanning two floors. Most of the books were faded from use or sunlight, the dust jackets bent, and they were all stacked and tilted in a way that suggested they’d actually been read. There were knickknacks piled up everywhere, and even more haphazardly tucked into bins or captured in jars.

It was hardly the image of a futurist’s office, and in sharp contrast to the Japandi workspaces you see going viral on X. Yet despite the sheer amount of stuff lying around in Kelly’s haven, nothing appeared like junk. Every object seemed to vibrate with meaning, begging you to ask, “What’s this for?” or “Where’d you get that?”

As I was scanning the lower rungs of the bookshelf, Kelly materialized on the indoor balcony and invited me upstairs to talk. He was wearing socks that were way too big—the spaces where his toes should have been were empty and flopped around in front of him—and his pants were stained from actual paint (i.e., not in the Rag & Bone way).

As I walked up the stairs, I asked him what the oldest object in the studio was, but he immediately deflected. No interest in nostalgia from the futurist, I guessed.

I slowed down as I walked by the second-floor wall of knickknacks and started scanning. Kelly caught me doing so, pulled some leather doohickey about the size of my hand off the shelf, and handed it to me.

“What do you think this is?” he asked. I twirled it around and desperately wanted to answer correctly, but figured that wasn’t the point. Still, I fumbled around nervously and couldn’t even eke out a guess. Probably sensing my anxiety, Kelly jumped in. “It’s a leather cap for an eagle.” He got it in Mongolia where there’s a tradition of using eagles to hunt, he explained. Now things were feeling looser. I got the feeling I could pull this thread about the Mongolian eagles or get another story. Kelly made my decision for me when he directed my attention to a small jar containing a little creature’s bones. “This is from a bird that flew into that window,” he said, pointing to a window over his desk. I nodded along with enthusiasm. “I freeze-dried them!” he said proudly.

We strolled over to his desk, where he asked me to try to lift a small but dense ball that was sitting on the floor next to it. I could barely get it above my ankle. Kelly told me it was made out of tungsten. “It has a similar density to gold,” he continued. “Now every time you see a criminal in the movies running away with a bag of tungsten, you’ll know how unrealistic it is.”

Greatness is overrated. It’s a form of extremism, and it comes with extreme vices that I have no interest in. Kevin Kelly

It was so much fun connecting with Kelly over these random little objects—I felt I was learning something about him I couldn’t through his books and blog posts; like I was getting to the real spirit he brings to his life and work. But before I could think too much, we were onto the next.

There was a train track running along the wall, just below the ceiling, and I asked if it worked. I half-expected him to yell, “Alexa, start your engines!” Instead, Kelly walked over to his desk and picked up a controller and turned it on. Nothing happened. He replaced the batteries, gave the controller a smack like it was a Nintendo 64 cartridge, and tried again. The train, looking like something my dad might have built at the model shop down the street in the 60s, immediately started choo-chooing around the room. Kelly stood and smiled proudly again as he watched it go. Eventually we took our seats next to his desk to talk.

I started off by asking him whether there is a unifying theme to his seemingly diffuse life’s work, which has included old-school magazines and books, bleeding-edge technology, conservationism, photographing Asia, and teaching. “Following my interests,” he said simply.

It sounded awfully cutesy for someone so accomplished. I said that there is an idiosyncratic magic to the way he follows his interests, which is that they’re not just an input; Kelly turns his interests into an output that he can share with others. When I asked if I was onto something, I learned that Kelly doesn’t think in outputs. For him, doing is part of learning. “I don’t really pursue a destination,” he said. “I pursue a direction.”

I asked him the difference between “following your interests” and being scatterbrained or having shiny object syndrome, like I sometimes worry I do. “The people who become legendary in their interests never feel they have arrived,” he said. When he talked about the power of passion and obsession in that process, I asked him if passion is enough. “Enough for what?” he asked, somewhat rhetorically. He had an impression of what I meant. “I think one of the least interesting reasons to be interested in something is money,” he said, and cited Walt Disney. “We don’t make movies to make money. We make money to make more movies.”

Money isn’t actually what I meant, but I appreciated that he took the conversation there. I let the silence hang for a minute before he continued. “What I’m talking about is taking your interests seriously enough to have the courage to stay moving. You can give stuff away. You can abandon things. You can tolerate failure because you know that tomorrow there is more.”

I asked Kelly about the tradeoffs of focusing on a single thing if you want to be great (which is what I had been getting at before). “Greatness is overrated,” he said, and I perked up. “It’s a form of extremism, and it comes with extreme vices that I have no interest in. Steve Jobs was a jerk. Bob Dylan is a jerk.”

The way Kelly approaches work differently was starting to come into focus.

Accounts of people pursuing their life’s work often include phrases like “maniacal focus” or “relentless pursuit.” I hear investors say they’re looking for founders with “a chip on their shoulder.” Facebook’s iconic ‘Little Red Book’ from 2012, which still serves as a pillar for peak tech culture, features a full-page spread that says ‘Greatness and comfort rarely coexist.’

A recent xeet from Reid Hoffman reads, “If a founder brags about having ‘a balanced life,’ I assume they’re not serious about winning.” Jensen Huang says he wants to “torture people into greatness.” When I was on the job hunt many years ago, an investor was pitching one of his portfolio companies by saying, with a wink, that the founder would do “whatever it takes to win.” I genuinely didn’t know what he meant by that, but it sent a shudder down my spine. Once I heard a serial founder say he started his second company “out of chaos and revenge.” I heard about another prominent CEO that looks in the mirror every morning and asks himself, “Why do you suck so much?” I read a biography of Elon Musk; he seems tortured. There’s some rumor floating around about how Sam Altman was so focused on building his first startup that he only ate ramen and got scurvy. According to Altman, “I never got tested but I think (I had it). I had extreme lethargy, sore legs, and bleeding gums.”

Compared to this, Kelly’s version of doing his life’s work seems so joyful, so buoyant. So much less … angsty. There’s no suffering or ego. It’s not about finding a hole in the market or a path to global domination. The yard stick isn’t based on net worth or shareholder value or number of users or employees. It’s based on an internal satisfaction meter, but not in a self-indulgent way. He certainly seeks resonance and wants to make an impact, but more in the way of a teacher. He breathes life into products or ideas, not out of a desire to win, but out of a desire to advance our collective thinking or action. His work and its impact unfold slowly, rather than by sheer force of will. Ideas or projects seem to tug at him, rather than reveal themselves on the other end of an internal cattle prod. His range is wide, but all his work somehow rhymes. It clearly comes very naturally for him to work this way, but it’s certainly not the norm.

If this is a way of living and working that’s available to all of us, why do we fetishize the white-knuckling and pain?

I know I’m not the first person to have the brilliant idea that we can do better work when we like it. I know that the whole ‘find your passion’ movement fell flat in its naivete. But I think somewhere along the way, the message about what it feels like to be great has become a bit perverted.

A few years ago, I forced myself to try and write down a professional goal. After several hours of forced meditation on the topic, all I could muster was ‘have a good day, most days.’ And don’t get me wrong, by ‘good day’ I don’t mean sitting by a pool drinking an Aperol Spritz. I feel alive when I launch something exciting, close a big deal, or build an elegant model. I enjoy the feeling of caring so much about something that it wakes me up in the middle of the night (it happened multiple times writing this piece). And yet, I imagined sharing my ambition to ‘have a good day, most days’ in a job interview—and decided to keep it to myself, because it probably doesn’t speak well of me.

But there I was, in front of a personal hero, whose most striking quality is that he seems to be having a nice day, most days. Why can’t we work and enjoy it? And I don’t mean in the masochistic sense.

I thought I was here to go deep on working Hollywood style, but as I sat there with Kelly in a room of what are best described as his toys, I realized that the most interesting thing about him is that he seems happy. At ease in the world and in his skin. I wasn’t there with Kelly for permission to work Hollywood style. I was there for permission to work with both ambition and joy.

If this is a way of living and working that’s available to all of us, why do we fetishize the white-knuckling and pain?

This shouldn’t make us defensive or self-conscious, but it does. I, like many others, want to be great. I want to feel commitment and camaraderie and work hard and be my best and impact top and bottom lines. But I don’t want to also feel tormented or be tortured into greatness or look in the mirror and wonder why I suck. But what does that say about me?

I want more role models like Kevin Kelly. People that proudly whistle while they work. Who have boundless energy and healthy gums. Whose enthusiasm is contagious. Who are well-adjusted and emotionally regulated. Who have solid relationships and happy families. Who are hungry and impactful and care deeply, without being jerks. And I want more people to talk about these qualities with respect and reverence.

I have never been a billionaire or built a unicorn, so I can’t speak with any conviction about what it requires. I won’t be eulogized anywhere important and no one 300 years from now will talk about what great things I did. But I want to live in a world where you can have an impact and be happy. Maybe that’s naive, but I’m sticking to it.

All of this occurs naturally to Kelly, and he doesn’t have complicated feelings about it. I’m hoping to get there myself by channeling him more. “The more you pursue interests,” he told me on the good day we spent together, “the more you realize that the well is bottomless.”

Brie Wolfson is the chief marketing officer of Colossus and Positive Sum.

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0