Possibly a Serious Possibility

Sherman Kent was rattled. It was March 1951 and Kent, a CIA analyst, had found himself in a troubling conversation about some recent intelligence. A few days earlier, Kent's team had released a report titled ‘Probability of an Invasion of Yugoslavia in 1951’, which concluded that Soviet aggression against Yugoslavia ‘should be considered a serious possibility’.

Kent thought the phrase was clear. But when he ran into the chairman of the Policy Planning Staff, he realised his message hadn’t landed as intended.

‘By the way, what did you mean by “serious possibility”?’ the chairman asked.

‘I told him that my personal estimate was on the dark side, namely that the odds were around 65 to 35 in favor of an attack’, Kent would later recall.

The chairman was taken aback. He—and others—had read the phrase as meaning something much less likely.

Things got worse when Kent talked to his colleagues on the Board of National Estimates. Some interpreted the phrase as meaning a probability as high as 80%, others as low as 20%. This was the 29th such report that they’d produced. ‘Had Board members been seeming to agree on five months' worth of estimative judgments with no real agreement at all?’ Kent wondered.

The latest report, intended to sound an alarm, had instead created confusion.

This wasn’t just a one-off problem. It was a structural flaw in how intelligence was being communicated at the time. Reflecting on the experience, Kent categorised intelligence assessments into three categories:

Near-indisputable facts, like the length of a runway visible in a satellite image.

Judgement or estimate of something knowable, like whether the runway belongs to a military airfield.

Judgement or estimate of something unknowable, like whether the airfield will be expanded into a strategic base. Even the adversary may not yet know what they’re going to do with it.

Kent noted that most intelligence work tends to sit in the second and third categories, where uncertainty dominates. But Kent realised that even among professionals, the language of such uncertainty was wildly inconsistent. Photo interpreters would use ‘possible’ where he would use ‘probable’. And they used ‘probable’ where Kent would say ‘almost certain’.

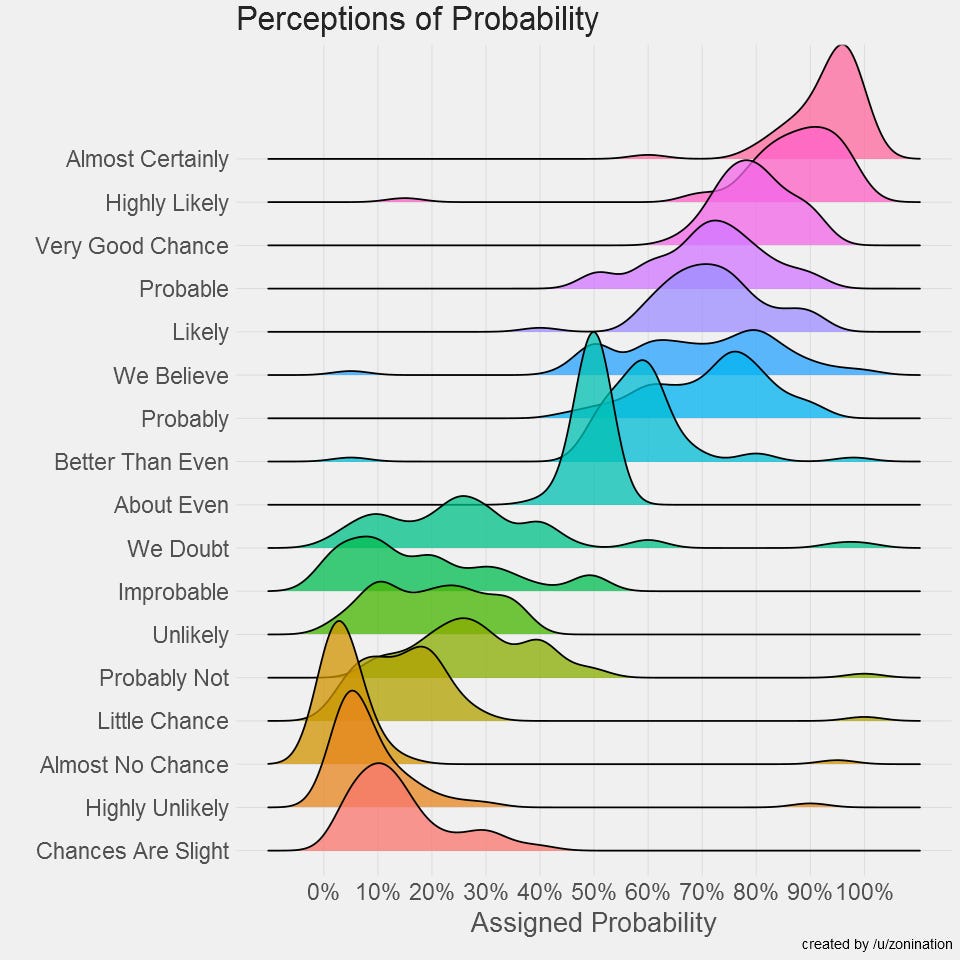

Decades later, a NATO study would find something similar: ask 23 officers what ‘likely’ means in terms of probability, and you’ll get a dozen different numbers. Modern online surveys show people haven’t improved much, as shown in the below data:

Kent suggested that the toughest intelligence challenge is the ‘difficult but not impossible estimate’. Unfortunately, this was also the kind of judgment people tried hardest to avoid. As Kent put it: ‘What we consciously or subconsciously seek is an expression which conveys a definite meaning but at the same time either absolves us completely of the responsibility or makes the estimate at enough removes from ourselves as not to implicate us’.

The problem reaches beyond the intelligence world. Legal scholars have found that courts also rely on ambiguous phrases for ambiguous evidence, with everything-to-everyone phrases like ‘non-whimsical suspicion’ or ‘clear indication’. To Kent, these kinds of ‘lurking weasel’ phrases were simply a way to avoid decisions: language that sounds authoritative but dodges responsibility. ‘Let the judgment be unmistakable and let it be unmistakably ours,’ as Kent put it.

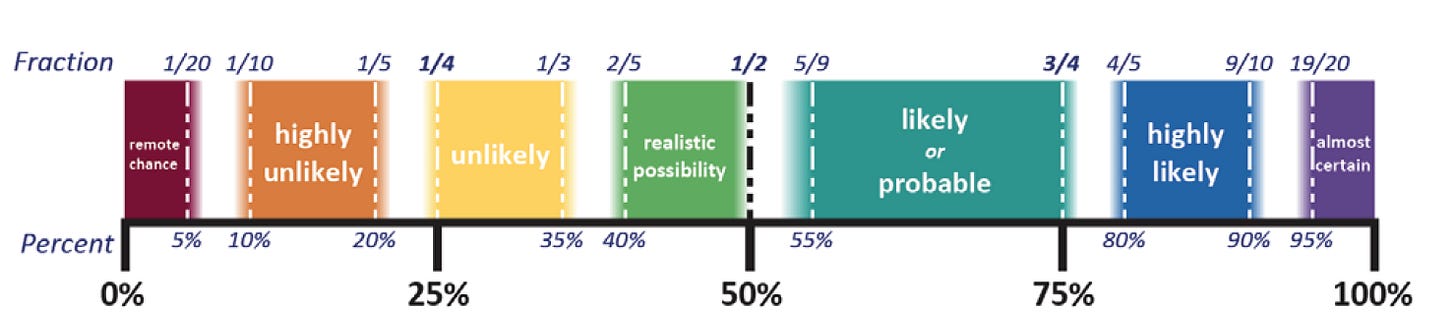

Since then, some governments have tried to clean up the language of probability. After the Iraq War—which was influenced by misinterpreted intelligence—the UK introduced a ‘probability yardstick’ for intelligence assessments, standardizing terms like ‘unlikely’, ‘highly likely’, and ‘probable’ with numerical definitions:

Such standarisation matters, because in a world where uncertainty is unavoidable, the risk isn’t just that we’re wrong—it’s that we’re misunderstood.

If you’re interested in reading more about analysing and communicating uncertainty, you’ll probably like my new book Proof: The Uncertain Science of Certainty, which is available now. It was reviewed in The New York Times this week if you’d like to know more.

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0