Facts don't change minds, structure does

Why Facts Don’t Change Minds in the Culture Wars—Structure Does

In 1633, Galileo Galilei stood before the Inquisition, not for inventing a radical new theory, but for proposing a straightforward idea: that the Earth moves around the Sun. This wasn’t even a new suggestion—Greek astronomers like Aristarchus had floated the heliocentric model centuries earlier. But in Galileo’s time, the idea ran into an insurmountable obstacle.

We often chalk up the Church’s resistance to superstition or ignorance. While that played a role, there was something deeper at work. The Church wielded immense power, but that power ultimately depended on the beliefs of the people. For society to function as the Church wanted, people needed to carry certain information in their heads—ideas that shaped how they behaved, what they valued, and whom they trusted. The Church had mastered the art of narrative dominance, building a system of stories, symbols, and doctrines that made its authority seem natural and inevitable. The geocentric model was one of the cornerstones of this narrative system.

The geocentric model formed a core part of Church doctrine and daily life. For example, Psalm 104:1-6 (KJV) reads:

Bless the Lord, O my soul. O Lord my God, thou art very great; thou art clothed with honour and majesty. Who coverest thyself with light as with a garment: who stretchest out the heavens like a curtain: Who layeth the beams of his chambers in the waters: who maketh the clouds his chariot: who walketh upon the wings of the wind: Who maketh his angels spirits; his ministers a flaming fire: Who laid the foundations of the earth, that it should not be removed for ever. Thou coveredst it with the deep as with a garment: the waters stood above the mountains.

Likewise, Joshua 10:12-13 (KJV) describes:

Then spake Joshua to the Lord in the day when the Lord delivered up the Amorites before the children of Israel, and he said in the sight of Israel, Sun, stand thou still upon Gibeon; and thou, Moon, in the valley of Ajalon. And the sun stood still, and the moon stayed, until the people had avenged themselves upon their enemies. Is not this written in the book of Jasher? So the sun stood still in the midst of heaven, and hasted not to go down about a whole day.

These passages were cited as literal proof that the Earth was stationary and central. This cosmic arrangement justified humanity’s special status: sermons and theological writings argued that God placed humans at the center of the universe, making them the focus of divine attention and salvation. The structure of the cosmos—Earth at the center, surrounded by concentric spheres of planets, stars, and heaven—mirrored the Church’s vision of a divinely ordained social and spiritual hierarchy.

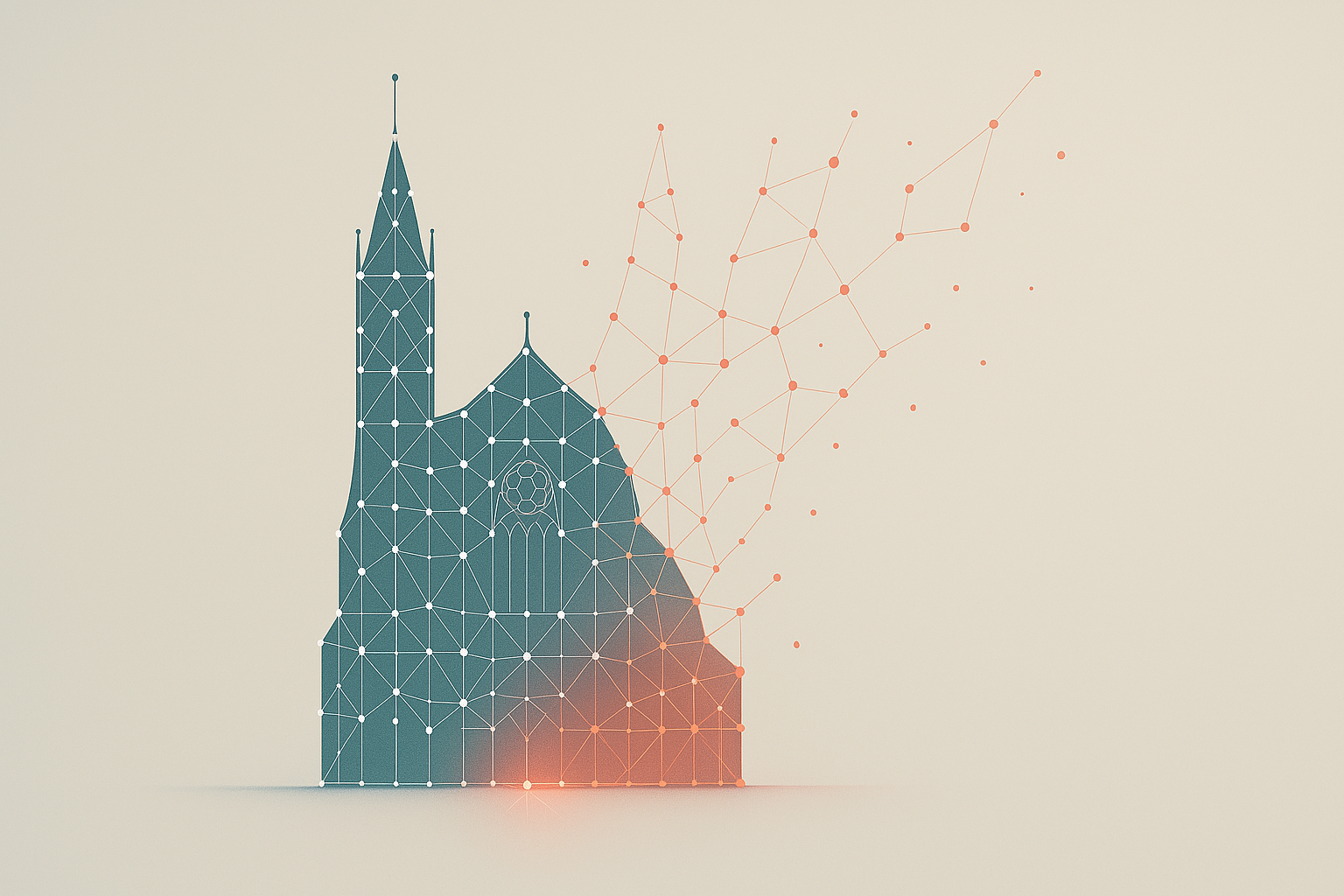

You could see this worldview in action throughout Christian life. The Church’s liturgical calendar—including the calculation of Easter—relied on the apparent movements of the Sun and Moon around a stationary Earth. Cathedrals like San Petronio in Bologna were equipped with meridian lines and astronomical clocks, turning the very architecture into solar observatories for tracking the heavens as seen from Earth’s center. In art, illuminated manuscripts and stained glass windows depicted the universe as a series of concentric spheres, with Earth at the heart of creation. The rose windows of Gothic cathedrals, with their radiating spokes, visually echoed the cosmic order, while creation scenes in church art often showed God setting the Sun, Moon, and stars in motion around a central Earth.

Miracles described in the Bible, like the Sun standing still for Joshua, made sense only in a geocentric universe. Even the moral order—the idea that the corrupt Earth was surrounded by the pure heavens—depended on this model. Accepting heliocentrism would have meant unraveling a whole tapestry of beliefs, not just about the stars, but about God, humanity, and the Church’s place in the world.

The Church’s worldview was a bonafide conceptual cathedral. Its visible rituals and teachings rested on a hidden architecture of interlocking ideas, each supporting and reinforcing the others. At the very foundation was the belief that Christianity—and specifically the Church—was the sole authority on interpreting reality. The geocentric model was a crucial supporting pillar: it was drawn directly from scripture and literally carved into the intellectual and physical fabric of Christian society. To question geocentrism was to question the explanatory power of scripture itself, and by extension, the Church’s authority to define what was true.

“To question geocentrism was to question the explanatory power of scripture itself, and by extension, the Church’s authority to define what was true.”

We can visualize this kind of belief system as a graph—a network of concepts, values, and connections. When you challenge a core idea, you’re not just questioning a single point; you’re tugging at the beams and arches of the entire cathedral.

“When you challenge a core idea, you’re not just questioning a single point; you’re tugging at the beams and arches of the entire cathedral.”

To make this more concrete, let’s look at two simplified versions of highly polarized belief templates: "Growth-First Capitalism" and "Ecological Sustainability." These are modern examples, but the same structural logic applies.

N.B. These are illustrative archetypes designed to show structural logic, not to represent the complex and varied beliefs of every individual who might identify with those labels.

The Anatomy of a Belief Graph #

Let's start by mapping our two competing systems. First, the "Growth-First Capitalism" graph. Its structure is tight, coherent, and self-stabilizing. Every part supports every other part, creating a remarkably stable architecture.

graph TD

subgraph "Growth-First Capitalism"

A["Innovation"] -- "drives" --> B["Profit"]

E["Shareholder Returns"] -- "results in" --> F["Purchasing Power"]

C["Competition"] -- "stimulates" --> A

A -- "enables" --> D["Efficiency"]

B -- "leads to" --> E

D -- "increases" --> B

F --> |"incentivizes"| C

end

Its rival, the "Ecological Sustainability" graph, is built on a different logic. It emphasizes the connection between human well-being and the health of the planet, valuing collective action and long-term resilience.

graph TD

subgraph "Ecological Sustainability Graph"

A["Climate Change Threat"] -- "motivates" --> B["Policy Change"]

B -- "enables" --> C["Renewable Energy Adoption"]

C -- "leads to" --> D["Reduced Emissions"]

D -- "supports" --> E["Resilient Communities"]

E --> |"reinforces support for"| B

end

Now, the crucial point: the "edges" in these graphs aren't just abstract connections. They are forged and reinforced in our minds by powerful psychological forces. When our beliefs conflict with evidence—a state called cognitive dissonance—our brains don't just sit with the discomfort. They automatically work to reduce it through motivated reasoning, unconsciously processing information in ways that preserve our existing worldview. We engage in post-hoc rationalization, constructing logical-sounding explanations for why contradictory evidence doesn't actually contradict our core beliefs. This is the cognitive engine that makes these belief structures so incredibly stable and resistant to change.

The Rules of Engagement #

These structural moves—attacking nodes or edges—play out not in abstract graphs, but in the minds of real people. The psychological mechanisms that defend or rewire these graphs are well-studied: motivated reasoning, cognitive dissonance, and the deep entanglement of belief and identity.

When belief systems interact, the real contest isn’t just about exchanging arguments—it’s about trying to reshape each other’s underlying structures. Each side looks for ways to weaken, sever, or absorb the connections that make the other system stable. Sometimes this means targeting a core idea, sometimes it means undermining the links between concepts, and sometimes it means co-opting a rival’s most appealing elements. The result isn’t just a clash of opinions, but a series of moves and countermoves that can change the very architecture of what people believe.

Node Attack (Targeted) #

Attacking a single, well-chosen node can do more damage than a thousand scattered arguments: it can destabilize or even collapse the entire structure from within.

Let’s walk through how a node attack can destabilize a belief graph in practice. In the first step, we can see the intact graph, All connections are strong. The system is stable and self-reinforcing.

graph TD

A["Climate Change Threat"] -- "motivates" --> B["Policy Change"]

B -- "enables" --> C["Renewable Energy Adoption"]

C -- "leads to" --> D["Reduced Emissions"]

D -- "supports" --> E["Resilient Communities"]

E -- "reinforces support for" --> B

A targeted campaign questions the "Climate Change Threat" node. When this happens, people whose worldview depends on this node experience cognitive dissonance—a psychological discomfort that arises when core beliefs are challenged. Motivated reasoning kicks in: the mind works unconsciously to defend the threatened node, searching for counterarguments or rationalizations. If the attack is persistent or persuasive enough, the connection to "Policy Change" weakens—not because the graph “wants” to survive, but because the brain is working to reduce discomfort and preserve coherence. As a result, the whole feedback loop runs at reduced capacity.

graph TD

A["Climate Change Threat (under attack)"] -. "motivates" .-> B["Policy Change"]

B -. "enables" .-> C["Renewable Energy Adoption"]

C -. "leads to" .-> D["Reduced Emissions"]

D -. "supports" .-> E["Resilient Communities"]

E -. "reinforces support for" .-> B

If the attack succeeds at its maximalist goals, the connection from "Climate Change Threat" to "Policy Change" is removed. The core system loop is now compromised and is beginning to disintegrate in a functional sense. The idea itself might persist in some capacity, but not enough to sustain itself, and is at high risk of complete disintegration over time.

graph TD

A["Climate Change Threat (discredited)"]

B["Policy Change"]

C["Renewable Energy Adoption"]

D["Reduced Emissions"]

E["Resilient Communities"]

B-. "enables" .-> C

D-. "supports" .-> E

In the intact system, belief in the climate threat drives a cascade of policy and action, reinforced by a feedback loop. When the core node is attacked, the motivation for policy change is weakened, and the system’s ability to mobilize is compromised. If the attack succeeds, the connection is severed. The core system loop is left wobbling, with all its connections weakened and the feedback loop broken. The belief system is now fragmented and far less able to sustain action or resist competing narratives. The individual pieces might recombine in the future and/or be absorbed into other graphs, since their current configuration might not anymore represent a structural threat.

Edge Attack (Severing Connections) #

Attacking the connections between ideas can force a belief system to reroute its logic, making it less direct, more convoluted, and sometimes less persuasive—even if the system doesn’t collapse outright.

Let’s walk through how an edge attack can destabilize a belief graph in practice, using the Growth-First Capitalism system:

In the intact system, all connections are strong. Profit leads to shareholder returns, which result in greater purchasing power, incentivizing further competition and innovation. The system is stable and self-reinforcing.

graph TD

subgraph "Growth-First Capitalism"

A["Innovation"] -- "drives" --> B["Profit"]

E["Shareholder Returns"] -- "results in" --> F["Purchasing Power"]

C["Competition"] -- "stimulates" --> A

A -- "enables" --> D["Efficiency"]

B -- "leads to" --> E

D -- "increases" --> B

F --> |"incentivizes"| C

end

A targeted critique questions whether shareholder returns actually translate to broad purchasing power (e.g., "returns only benefit a small elite"). Here, the attack isn’t on a core belief, but on the connection between two ideas.

graph TD

subgraph "Growth-First Capitalism"

A["Innovation"] -- "drives" --> B["Profit"]

E["Shareholder Returns"] -. "results in" .-> F["Purchasing Power"]

C["Competition"] -- "stimulates" --> A

A -- "enables" --> D["Efficiency"]

B -- "leads to" --> E

D -- "increases" --> B

F --> |"incentivizes"| C

end

The mind’s “pattern completion” instinct tries to fill the gap, but if the critique is strong, the link weakens. People may experience a subtle sense of unease or doubt, leading to rationalizations or even compartmentalization—where the two ideas are held separately to avoid conflict. The arrow from Shareholder Returns to Purchasing Power is now severed, weakening the broad appeal of the whole.

graph TD

subgraph "Growth-First Capitalism"

A["Innovation"] -- "drives" --> B["Profit"]

E["Shareholder Returns"]

F["Purchasing Power"]

C["Competition"] -- "stimulates" --> A

A -- "enables" --> D["Efficiency"]

B -- "leads to" --> E

D -- "increases" --> B

%% No arrow from E to F

end

In the intact system, profit leads to shareholder returns, which result in greater purchasing power, incentivizing further competition and innovation. When the link from shareholder returns to purchasing power is attacked, the system’s claim to broad prosperity is weakened. The narrative shifts toward profit benefiting only a select group. If the connection is severed, the system is reinterpreted entirely as serving primarily shareholders, undermining its legitimacy and making it more vulnerable to critique or alternative models. The feedback loop is still there, but it is shown to benefit the select few, and the system becomes less persuasive and more vulnerable to further attacks or absorption by rival graphs.

“Attacking the connections between ideas can force a belief system to reroute its logic, making it less direct, more convoluted, and sometimes less persuasive—even if the system doesn’t collapse outright.”

These two examples—targeting a core node and severing a key connection—capture the essence of how belief systems compete and adapt. There are other, more sophisticated tactics as well: sometimes a system absorbs a rival’s most appealing ideas, sometimes it evolves to occupy a different niche, and sometimes it builds resilience through self-correction. If you want to explore these further, you’ll find a full taxonomy of competitive mechanisms in section 5a of the ontology.

But for most real-world debates, understanding how nodes and edges are attacked or defended will take you a long way toward seeing the mechanical structure beneath the surface of any argument.

The Human Element #

People have a wide range of intuitions about the agency of information systems. Some see belief systems—memes, ideologies, conceptual structures—as almost agentic, evolving and competing for survival. Others view them as nothing more than abstractions, with real agency residing only in human minds. In practice, the persistence and apparent self-preservation of belief structures is a result of the architecture of human cognition, not the intentions or desires of the information systems themselves.

“The persistence and apparent self-preservation of belief structures is a result of the architecture of human cognition, not the intentions or desires of the information systems themselves.”

Cognitive science gives us the tools to understand this dynamic. When you are arguing with someone who is deeply embedded in a different belief graph, you’re not just trying to change one opinion. You’re engaging with a network of ideas that is stabilized by powerful psychological mechanisms.

Our brains unconsciously process information in ways that protect our existing worldview, filtering out threats and rationalizing contradictions through motivated reasoning. When confronted with evidence that conflicts with our beliefs, we experience cognitive dissonance and instinctively seek to resolve it—often by rejecting the evidence or reinterpreting it to fit our structure. Sometimes, our sense of self becomes so tightly bound to a belief graph that any challenge to the system feels like a personal attack.

These mechanisms don’t give information systems agency, but they do make belief structures remarkably stable and resistant to change. The “immune system” of the mind kicks in, not because the graph wants to survive, but because our brains are wired to defend the patterns that give us coherence and identity.

So when you encounter someone whose worldview seems impenetrable, remember: you’re not just arguing with a person, you’re engaging with a living, self-stabilizing information pattern—one that is enacted and protected by the very architecture of human cognition.

Clashing Templates in the Culture Wars #

Much of today’s public discourse isn’t really about facts or even about individual arguments—it’s about incompatible templates clashing. Each side brings a different structure, a different set of core nodes and connections, and tries to impose its logic on the other. The result is less a debate and more a collision of worldviews, where neither side can easily accept the other’s premises, let alone their conclusions.

“Much of today’s public discourse isn’t really about facts or even about individual arguments—it’s about incompatible templates clashing.”

From a strategic, geopolitical perspective, the balance of power in any culture war depends not just on the strength of each pole, but on the internal coherence of each side’s belief structures. When a group’s internal graph is tightly connected and mutually reinforcing, it can project influence and resist outside attacks. But when a side is internally divided—when its graph is fragmented or its core connections are weakened—its overall influence diminishes. This makes destabilization a high-return strategy for adversaries: by sowing division or attacking key connections within a rival’s belief system, even a relatively weak actor can shift the balance of power in their favor.

Structural Competition in Action: Coordinated Inauthentic Behavior #

The term “coordinated inauthentic behavior” was coined by social media platforms to describe organized campaigns where multiple fake accounts work together to manipulate public opinion. Unlike simple spam or individual trolls, these operations create the illusion of grassroots support for specific narratives, making fringe ideas appear mainstream and legitimate.

“Coordinated inauthentic behavior isn’t just about spreading falsehoods—it’s about systematically attacking the connections that hold belief graphs together.”

Coordinated inauthentic behavior—from traditional troll farms to increasingly automated campaigns—represents structural competition at scale. These operations don’t just spread false information; they systematically attack the connections that hold belief graphs together.

The Russian Internet Research Agency (IRA) provides a perfect case study. Their operations weren’t just about spreading misinformation—they were systematic attacks on the structural integrity of American, and more broadly "Western", belief systems.

Take their approach to racial tensions. Rather than directly attacking specific facts, they created competing narratives that severed connections between different groups’ belief graphs. They simultaneously supported Black Lives Matter protests AND organized counter-protests, not to advance any particular cause, but to create social chaos that would make people’s belief in American institutions less coherent.

A similar pattern played out in the vaccination "debate." Russian-linked accounts amplified both pro-vaccine and anti-vaccine content, not to promote public health or skepticism, but to maximize confusion, distrust, and polarization within the population. (American Journal of Public Health, 2018)

The same playbook has been used in the climate change debate. Russian disinformation campaigns have amplified both climate denial and divisive narratives—such as framing climate action as a Western plot or as harmful to ordinary people—to polarize Western societies and undermine collective action. (CEU, 2024; Strudwicke & Grant, 2020).

What made the IRA effective wasn’t the individual posts—it was the cumulative effect of thousands of coordinated messages, each designed to weaken specific connections in people’s belief graphs. When enough connections are severed, entire worldviews become unstable, creating fertile ground for competing belief systems to take root.

“When enough connections are severed, entire worldviews become unstable, creating fertile ground for competing belief systems to take root.”

Microtargeting technologies, as seen in the Cambridge Analytica scandal, were already exceedingly effective at identifying and exploiting the most vulnerable nodes and edges in people’s belief structures—long before the advent of large language models (LLMs). By harvesting personal data and delivering highly personalized messages, these campaigns could subtly rewire how individuals interpret the world (The Guardian, 2018; NYT, 2018). With the rise of LLMs, the power and scale of such structural manipulation has increased dramatically, enabling the generation of thousands of tailored variations and the potential to reshape belief systems at unprecedented speed and precision.

Today, this same structural approach is becoming infinitely more scalable. Where the IRA required hundreds of human operators, modern campaigns can use large language models to generate thousands of variations of the same structural attacks, each tailored to different audiences and platforms.

Architects of Our Own Understanding #

For years, our main defense against misinformation and manipulation has been to double down on “truth”—to fact-check, debunk, and moderate. These efforts are important, but they rest on the assumption that truth is the main determinant of what people believe. The evidence, and the argument of this post, suggest otherwise: structure, coherence, and emotional resonance are far more important for the persistence and spread of beliefs.

If we want to counter manipulation and polarization, we need to focus on strengthening the structural integrity and resilience of our own belief systems. This means fostering internal coherence, building bridges between different templates, and cultivating narratives that are not just factually accurate, but also emotionally compelling and structurally robust.

Truth matters—but it survives and spreads only when it is woven into a structure that people can inhabit.

“Truth matters—but it survives and spreads only when it is woven into a structure that people can inhabit.”

By understanding the mechanics of belief, we can become more than just passive hosts for warring systems. We can become the architects of our own understanding, building belief structures that are resilient, adaptive, and open to connection.

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0